Jane Fine: Love, American Style

Pierogi, New York

September 5 – October 7, 2018

Like a lot of contemporary paintings venting the Id, irreverence greets the eye in Jane Fine’s “Love American Style.” Symbols of greed and oppression gathering in tempestuous clumps are mollified by flowers, rainbows, stars and stripes in swathes of cheerful color. Working in acrylic, Fine’s linear descriptions overlay and largely conduct composition. Excess in content is firmly joined to formal infrastructure — textures and colors, shapes and lines, etc. all puzzled together. Painting’s power to beautify dark feeling, particularly in the more somber-hued small works, is masterfully on display.

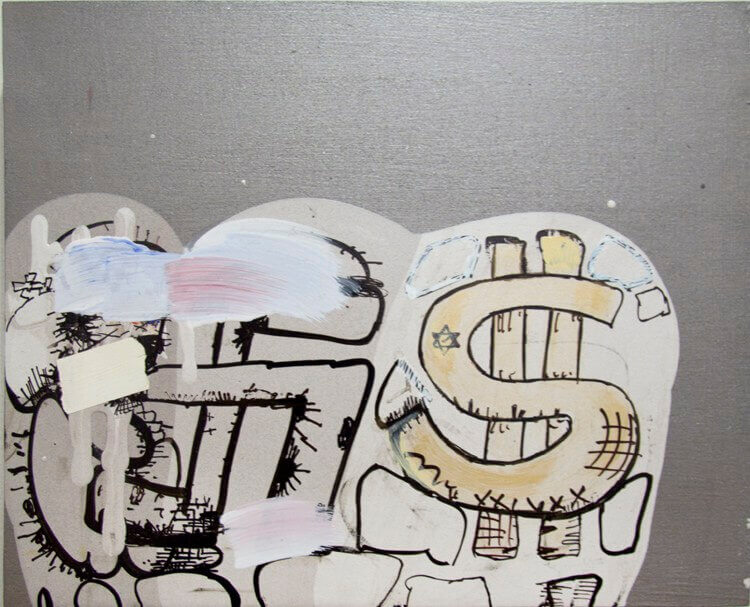

With a Dubuffet-like vigor, smaller pictures fasten the intimacy of diaristic process to the detachment of solid construction. In “Unpresidented” a dollar sign leads a swastika hastily disguised in pastel patches through an unkempt bubble, grinning as it gets away with it. In “Ministry of Plenty” an elephantine form full of mayhem and disrepair coheres; as vertical paint stripes slowly pool into feet it scatologically erupts leftward. Because subtle compositional timing controls emotional delivery, Fine’s painterly freshness has more clout than many contemporary paintings that look better digitally than “in the flesh”.

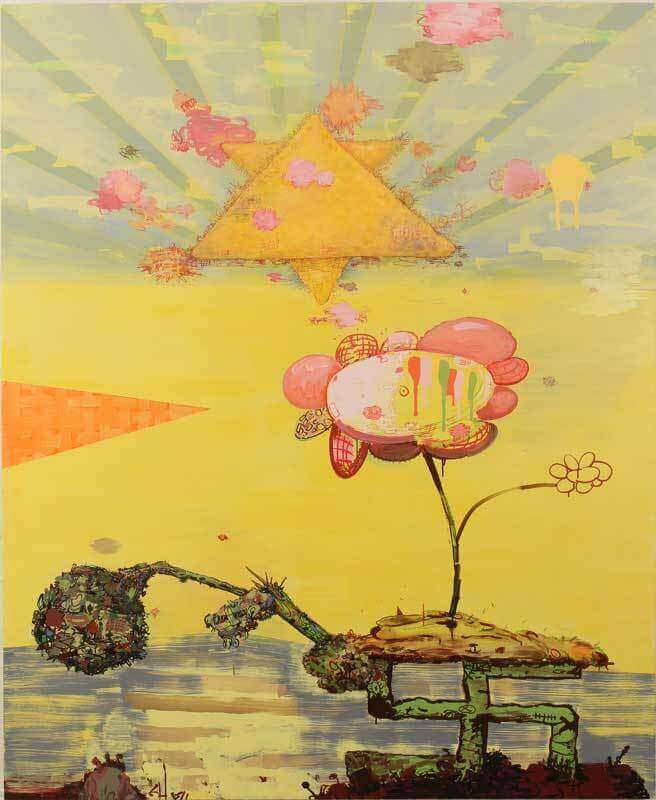

The hierarchical narrative of the engagingly clumsy “Rise Up” complicates the expressive spectrum of ire, desperation, vulnerability, and comic relief. A swastika mired to the bottom of the canvas begets a heavy growth failing left, as its goofy twin thrives, happy as a parasite. The flower reaches upward, flawed and buoyant, like a Dr. Seuss character — which Trump at his Homer Simpson best is. At the top a Jewish star-shaped sun beams rays heavenward.

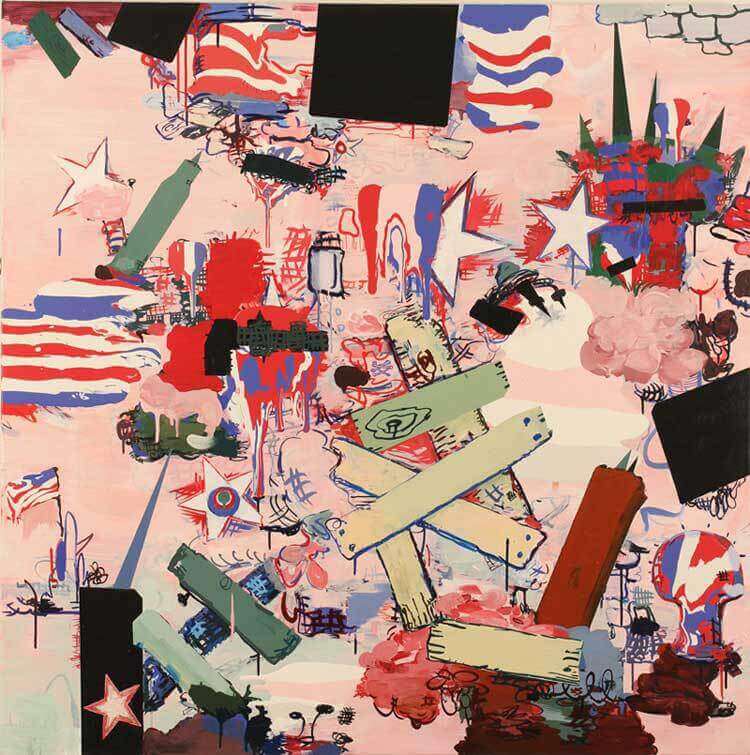

Sad to funny is a gamut Guston’s late paintings also observe, and Fine’s admiration for the master persists, as in the recurring criss-crosses offering haphazard protection or discretion. Like a hastily boarded window in the path of a hurricane, these “emojis” batten the picture plane of “So Much Winning” in futility. Chaotic patriotic paraphernalia disintegrates like an exploding Childe Hassam, trumpeting and entropy bypassing the nostalgic fragmentation of Charles Ives for John Phillip Souza on acid – a not inapt description of Trump’s jerry-rigged speeches. Here and there severe, black shapes hang around like useless redactions.

In the larger works formal language is more relaxed — colorful patchwork akin to Terry Winters’, along with a relaxed coziness like Marsden Hartley’s, render conflict more captivating than disturbing. In “Crystal Night” reference to the anti-Semitic window-breaking that portended the Holocaust seems echoed in a duplicitous rainbow streaming from a careening mudball. A saturated orange backdrop maintains order as things fall apart. Splotches of color, as in other paintings, appear almost flung at the surface — painter as captive primate, or a George Harriman brick-wielding interlocutor? A cool, formless shape shadows (or anticipates?) the pile of paint above biomorphically delineated into cynical detritus.

Although alluding to our disappointing head of state, the press release explains these paintings were impelled by sudden knowledge of unsure paternity. Guston’s bulbs, soles and departing overcoats lament his father obviously in retrospect, while change of basic identity seems a timeless shock, and the exponential rhyming of paternity and patria leans toward foreboding. Unsurprisingly then, Fine’s paintings lack the tenderness Guston’s autobiographical work offered to his disappointments, including himself, to forgive.

In the deft, striking, small negative “NYET” curly Qs resemble barbed wire in an exciting conglomeration of figure ground reversals suggesting a map of the USA. Irate critique and ironic caricature trade-off, as do English and Russian. A speech bubble is bandaged or in bondage. In these uncertain times the strongest center that can hold appears to be NO.