Ordinarily online interviews are single session affairs or else a back-and-forth email conversation that lasts several days or weeks at most. Thus, they tend to focus on a particular body of work and present the artist’s thoughts at a discrete moment in time. Emil Robinson and I, however, have maintained an occasional correspondence that has lasted several years, beginning in the fall 2013 and continuing until this past spring. By generously sharing his work and ideas over months and years, Robinson has provided a rare and unique look into how he, as an artist, thinks and feels in paint. His images and thoughts show how underlying ideas and forces play out in different ways over time – how work comes out of work. One common thread that runs through all of Robinson’s work is a complex psychology – a tension and a depth of feeling that results from intense and perceptive observation. In his paintings, feelings become graspable. Robinson’s subjects are evocative and dreamlike, but they also exist right in front of you.

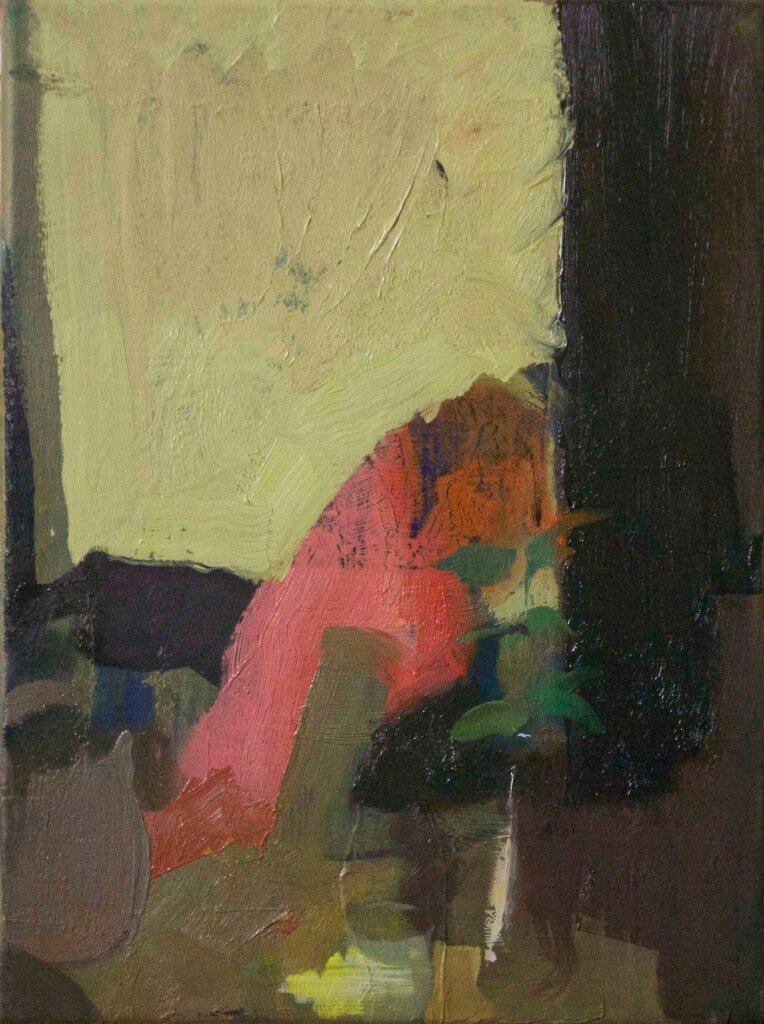

Emil Robinson (ER): I wanted to share some recent works [from 2014]. I have had an ongoing interest in interior space as you know, and I have recently found some success trying to manifest my interests in the form of small minimal interiors. I did a series of paintings of doorways a couple years ago, and I have just started another series of the same motif. The paintings deal with the color and light within, and on the outside of a doorway in the design school where I teach. Tonality is limited and the sparseness of dynamic change in color and value has required me to look harder and trust experiential color.

Brett Baker (BB): Your new small paintings look interesting – more abstracted [than earlier works] but still closely observed. I like in your new pieces how the minimal description of forms amplifies the apparent physical character of light – when it floods the structure for instance or when its relative intensity reverses the spatial emphasis. The latter is all the more interesting because the values are similar and in a middle range; the particular juxtaposition does the work. The overall impression is that the light is extremely active – invading and suffusing the space.

ER: “… how the minimal description of forms amplifies the apparent physical character of light…” That is the basic idea, One thing that I know about my work is that it has always been concerned with light. Some of my favorite American artists have been especially interested in the physicality of light: Edward Hopper, Richard Diebenkorn, and James Turrell all come to mind. There is something psychologically potent about the presence of a block of light on the wall. It is an affirmation of our physical world, but also a reminder of the interior world of the mind, the presence of our own perception of how things are, or how they could be.

In my recent doorway paintings it is the mutability of space through careful observation. For me this takes working from life in a new direction: I spend time looking at the subject, feeling the air in the room, imagining the weather and light outside by seeing the qualities of light on the wall inside the doorframe, and just quietly centering myself inside. As I continue to focus on the light in the doorway my mind begins to play tricks on me, colors start changing and everything seems liquid. At a certain point I see surprising things- almost hallucinations. I don’t mix colors until I start to see things. I have to find this place so that I don’t make an obvious painting. I trust my own experience in that moment. Many times the colors that result are almost identical in value and they exist as visual sensations in a seemingly uninterrupted patch of light. Some of the paintings also have the basic architectural certainty of a doorframe, others just have the field of color interaction. There are multiple “takes” on each panel, but they all share the same general light conditions as their perceptual underpinning. This means as the layers overlap and vibrate they stay within a similar register of color space. Many times the final layer consists of a simple interaction of a couple colors dragged over the field of the rectangle. My hope is that the psychological response I have is translated into an experience for the viewer. It is really exciting to think that a simple field of color might become the sensation of light and air.

BB: I love the image of light as a “block” – a physical mass. It’s also interesting to hear perceptual painting described in terms of perceiving unseen forces (“feeling the air”) rather than retinal phenomena. What (if any) is your relationship to a painter like Braque? He was an observational painter and I would argue his perception was direct, but his translation of that perception on the canvas was not; he is certainly not a perceptual painter in the way we might use the term today. Yet he meditated on the form and light he perceived around him and turned these observations into a type of psychological response. He also spoke of sight in terms of touch.

ER: I grew up with Rainer Rilke’s poetry around the house and he speaks of solitude as a state of grace. I used to be afraid of the connotation of that, I confused solitude with loneliness, which I knew I didn’t want. The solitude that Rilke speaks of is a realization of the unique qualities of one person’s heart:

“The work of the eyes is done. Go now and do the heart-work on the images imprisoned within you.”

People seem more lonely today but less solitary within themselves. I think art that comes from a solitary place is more important and exciting as a result.

BB: “The work of the eyes is done” is certainly an interesting quote to hear from an observational painter, as is the notion that images are “imprisoned within…” Applied to your paintings though, these notions speak to the kinds of interior spaces you paint, the rooms of your house at different times of day, for instance, or your color, which can be muted, but also evokes a rich vision of everyday experience. Now that I think about it, your more recent paintings turn everyday domestic experiences – selecting a DVD, late night movie watching – into visions. It’s like you’re with Vuillard in the beginning but in the end you’re with Redon – there’s a tension between the commonplace and the phantasmagoric.

BB: I consider myself at the moment an abstract painter enthralled with observational painting, but one issue I have with post-war and contemporary figurative painting is how overbearing the “abstraction” can be sometimes. The abstract armatures often seem to contribute more to the aura of seriousness than they do to the subject. In your work though I am struck by a more relaxed, natural relationship with abstraction. In your recent paintings [from 2014] the abstraction is “noticed” rather than constructed. There’s a natural anonymity to the abstract structure that allows the subject to be more expressive. It’s like you’re alert to the formality that simply is – that exists in our immediate environment. For me this allows the formal structure of the paintings to be experienced as moments – fresh and strange.

ER: Interesting thoughts on abstraction, I agree that constructed or forced abstraction can be a problem, especially when it is used as an aura of seriousness as you so aptly implied. At the same time I have a real love of figurative artists who construct their pictures with a sense of rigor: Piero, or more recently Euan Uglow or Balthus. I think this type of painterly game can become its own kind of prescription, but I am also mistrustful of simply recording a strange visual occurrence faithfully. I don’t like to copy a picture of something, there needs to be a discovery in the painting process. The parts of the work, although inseparable, subject, form, need to have a charged relationship.

BB: I was making that point about overly constructed figuration partly to point out that the dominance of abstraction of the second half of the 20th century is a hurdle for everyone, but also to point out that it seems less so for you – there are paintings of yours in which the pleasure/strength of construction is evident – and is a positive force, but also, particularly recently, that same pleasure of construction seems to be strengthened by being both “found” – a given of the noticed scene – and based in an experience and then developed from it. Am I way off?

ER: For my most recent series of small paintings, light in a doorway becomes physical. I am trying to paint in such a way as to have diversity and sensitivity through looking, but not be tied to description or illusion of form. I like to think that the paintings are fully tied to nature and fully rich in surface and physicality at the same time. Adventures within the space of something so mundane that it is completely unnoticed. I am trying my best to be a better listener to the world. I just heard a quote from Jake Berthot who is a painter I admire. Berthot said that the form of the painting will take care of itself if the artist has a source for his inspiration.

BB: Jake Berthot was a great painter, and it seems that his pursuit of inspiration you mention is at the root of his adoption of landscape and still life subject matter. His conviction about the importance of motivations changed his art. I prefer the word information to inspiration, though. Inspiration, I think, refers to the inherently difficult and mysterious nature of human interest. But that’s only part of it – you have to act, and you act on information. Something becomes interesting to us and then we study it; we use information from it, question it, and from this process we arrive somewhere new. It has been my experience that source information is crucial, but finding true sources is elusive and often comes out of the work. What begins as an instinctive move, or a series of moves in a painting changes the way you see, and the next painting investigates this altered source. This happens many times over many years in many paintings, and suddenly what’s before you is the same, but you are completely different.

ER: I try to treat my initial inspiration like the sound of feet on a path coming towards you in the dark, you can’t quite tell who is there, it might be anyone! Which also ties into your [previous] question about influence of other artists like Braque. I think Braque is absolutely fantastic. I agree that his decisions feel tied to nature, effortless in their invention and unfettered by calculation. There is something especially resonant in the way he depicts objects in such a humble and clear way, I prefer him to Picasso many times for this reason. It feels like a boat painted by Braque is really a boat, Picasso can feel like he is showing off. I find kinship in Braque’s temperament. The other two artists you mentioned are absolute favorites of mine: Vuillard and Redon. I like the belief in the unbelievable present in both of them and an obsession with light and atmosphere. Redon holds a special place for me due to the intensity of his private belief system. I had to look up “phantasmagorical” I forgot what it meant, but I really do love that notion. Fantastic things depicted as if they are commonplace. Maybe for me, it is more along the lines of commonplace things depicted so that a fantasy life becomes clear. In subject matter and temperament I have always loved certain american writers of the short story for this reason. Sherwood Anderson’s seminal book Winesburg Ohio is a favorite of mine. The book is almost as cozy as Little House On the Prairie, but the inner restlessness of the main characters creates a sense of potential and the strangeness of daily life is revealed. That spiritual churning is the real content of the stories. We all share feelings of restlessness when everything should be fine. I try to create this type of tension where the objects in a room and the actions happening are strangely magnetic, as if just out of reach of comfortable explanation.

BB: In Braque’s work there’s a straightforwardness without a willfulness – he’s looking at his canvas with the same wonder he has when he’s looking at a simple collection of objects. His paintings are maze-like in that they map the strange way that attention and focus shift over time, one day a vase will be mesmerizing, the next it’s nearly transparent and something else – a napkin, a stove pipe, or a wallpaper pattern – has become the most real for him.

I haven’t read Anderson (now I will), but the play between abstract feeling (the strangeness you refer to- as opposed to construction) expressed as a tangible reality holds real fascination for me.

ER: Just reread what you said about inspiration a couple comments back, really great! The constant unraveling of one’s motivations to find new, more personal information which in turn creates new choices etc. – fantastic and totally true. I feel like I am so early in my journey, but some recent things feel more right to me. One new twist this summer to my process is starting with images that I did not take myself. Not as a mantra, but as an option if the image seems especially ripe for me. I like the idea of images being touchstones that can help me find my voice even though the origin of the image may share little with my life experience. I feel open to this option because I am more confident in my voice as a painter. The image is more of a starting point than a guide for working. I am hoping that the nameable content of the work will diversify and grow more mysterious, but the work as a whole will contain the essence of a perspective more fully. On a related note, I that the power of a painting hinges on its conviction. The subject and form of the work can take any conceivable journey as long as the end result convinces the viewer they are experiencing something new. “Strangeness” yet a “tangible reality” as you so beautifully put it.

BB: I like the idea that finding one’s voice involves a pursuit of the diverse and mysterious. One overused art term I despise is “practice,” another is “clarity.” I don’t like them because they both suggest the need to set premature limitations on what one’s art can be rather than undertaking a journey to find out what it might become. It’s also interesting that you describe “newness” as the result of a journey. Much art today seeks to be new through calculated re-contextualization of an existing style, content, or other concerns. I don’t think it’s well understood that subject matter exists in art primarily as a facilitator of expression, not the expression itself.

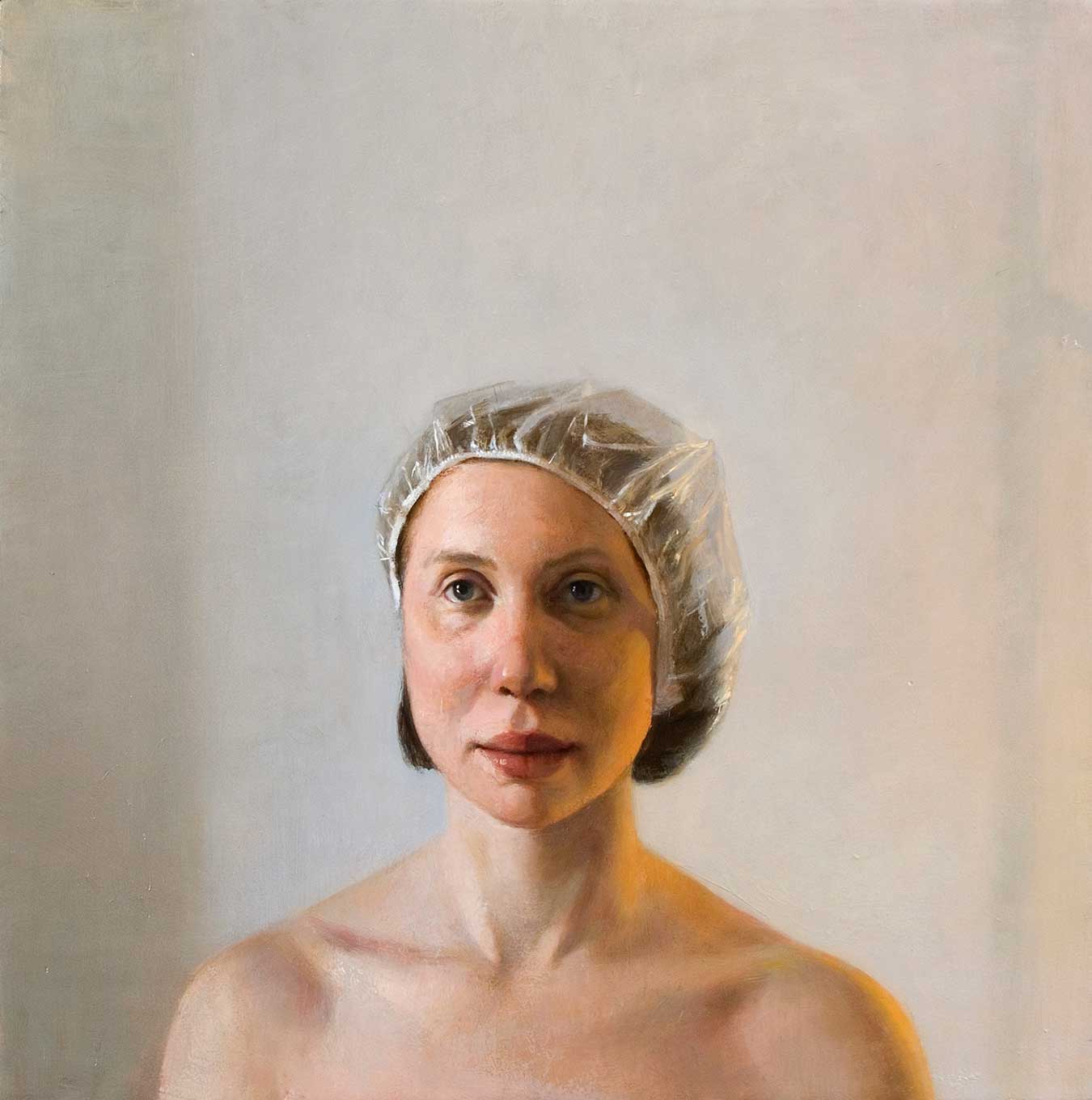

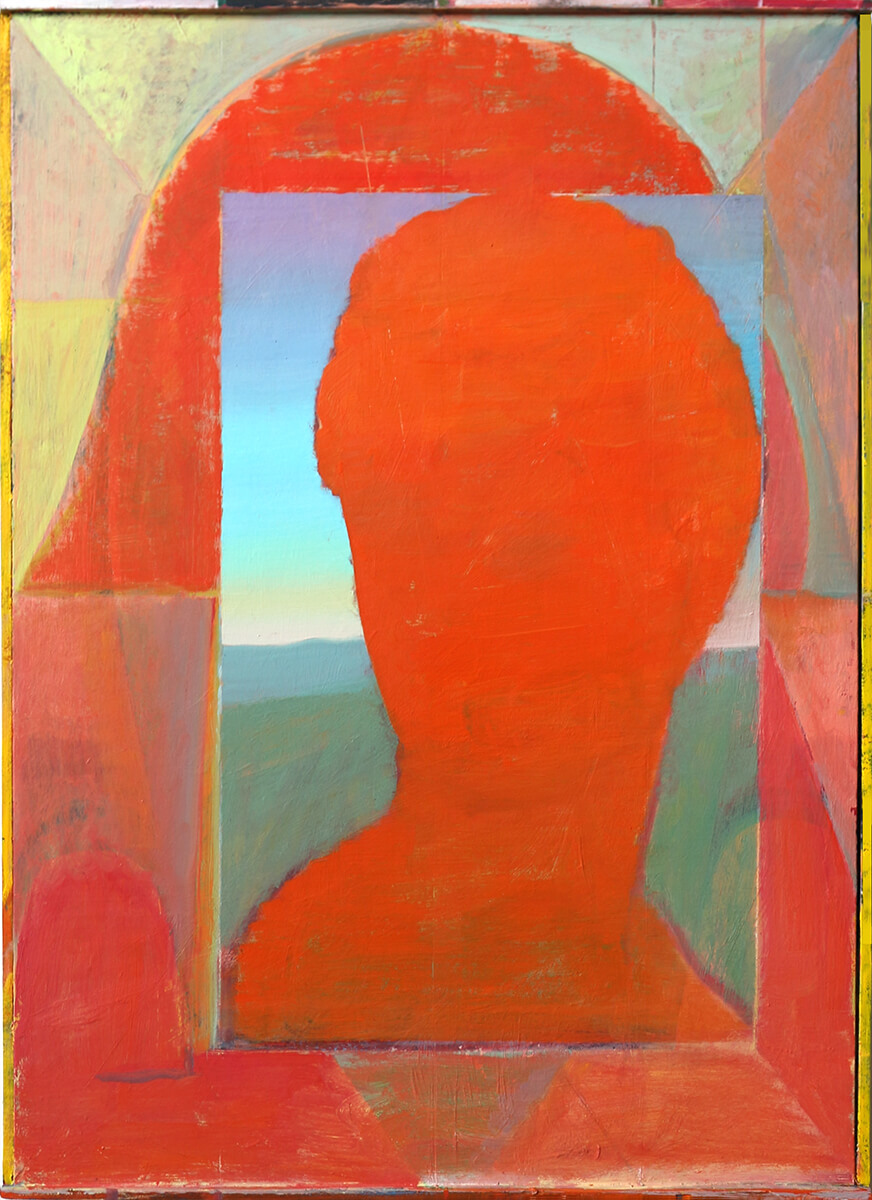

BB: Wow, I just realized that we’ve been talking on and off for almost two years! That’s the longest interview I’ve ever done. But I was thinking how great that is because your work has changed in many ways in that time, so there’s a before and after opportunity (or before and “now”) that doesn’t normally happen in these discussions, and which is really interesting. Looking at your recent work [from 2015-16], I thought about your painting “Showered” from 2007 which was the first painting of yours that came to my attention about five years ago. The careful observation in that painting is notable, but it’s also striking in that it feels very psychologically evocative. The paintings of interiors we discussed last year are also evocative in this way, and, to me, the new “Portraits of Scientists” paintings are too. It seems like this issue of psychological tension and depth persists in all your work, but how you examine and pursue it is what has changed.

ER: Paying attention to someone’s feelings creates intimacy between you and that person. In my paintings I try to have an open process to allow the paintings to become intimate. Maintaining psychological pitch feels like riding a horse. The horse knows what you are thinking and if you don’t maintain clarity of purpose and confidence then you won’t get anywhere. I have to fully give in to the simplicity of making paintings if I want to maintain intensity. Simplicity means not much thinking, just building. This intensity is like a frequency I can sometimes tune in to. Occasionally I make a painting in a natural way. Some paintings are very difficult to engage meaningfully and others are born gracefully. Both kinds of labor are natural eventually if the painting is to appear. This quality of being natural has to do with a personal suspension of disbelief maintained through material and image equilibrium. This has always been true for me even at very different periods in my work. As my adult life has required me to feel things more powerfully, I try to match the pitch of my paintings to this new range of my feelings.

Because I come from a Catholic upbringing with a strong belief in mysticism I like the idea of being a conduit for something spiritual. If my paintings hold a specific kind of personal psychology, it is a fear and curiosity about the unknown of death and presence or absence of God. When I make a painting, especially one that contains recognizable imagery, I would like to find the kernel of the thing that is inherently mysterious.

Robert Storr recently wrote an article on the interesting paintings of Rick Briggs where he commented that paintings should initiate a viewer’s interaction by creating the question: “What’s that?” Although I agree generally with this statement, my own priorities would rephrase this question as: “How do I relate to this?”

BB: It also seems like both your older and newer work is image driven (as opposed to process driven), but your concept of what “image” is has grown to encompass the entire painting, including the support. Even though there’s more visible process happening in the new paintings, would you still characterize them as “image” driven?

ER: Images have always been part of a compelling reason to paint. I like the idea that you can never quite get it right with an image. As long as the thing you are interested in is un-nameable to begin with. As a figurative artist I operate as someone who has hunches about the importance of an image to me. I actively exercise my intuition to trust these hunches. I have never wanted my paintings to be about visual reality. I make them because I want to share something. I think artists feel like outsiders in many instances of normal society. I had a vibrant and loving family life as a child, but school and other social childhood activities like sports, swim lessons, gymnastics, camp… they were just hard. I went to a strict Catholic grade school and I remember sitting in class or church and imagining a body-sized bubble floating in and picking me up. In the bubble no-one could hear me and I could fly around and watch everyone. I would imagine a lot of children experience this kind of fantasy. I felt a fissure between how things felt and looked to me and how they were expressed by the world around me.

BB: Since you have such an obviously strong background in perceptual painting, can you elaborate a bit on how that background and approach contributes to your newest work? I’m also curious how the custom supports came about.

ER: Catholic teaching posits a difficult but inextricable relationship between the soul and the body. The rituals of Catholicism reckon with this difficulty. Like many artists, I consider my work ritualistic. My desire to work with sculptural panels came from equating the physical painting and the body. The painted image represents the consciousness of the body. Part of my job is to get the two to be held in balance and relationship. Both are spiritually and aesthetically powerful. In my opinion the more recent works of the late Jake Berthot are high water marks for a balance between image and the reality a painting possesses. Reality in this case is the ability of a painted support to assert its bodily unity with nature. Berthot’s works depict recognizable images, but these images seem like thoughts or visions, materially inseparable from the container they fill. Maybe the dream world of the painted body they inhabit.

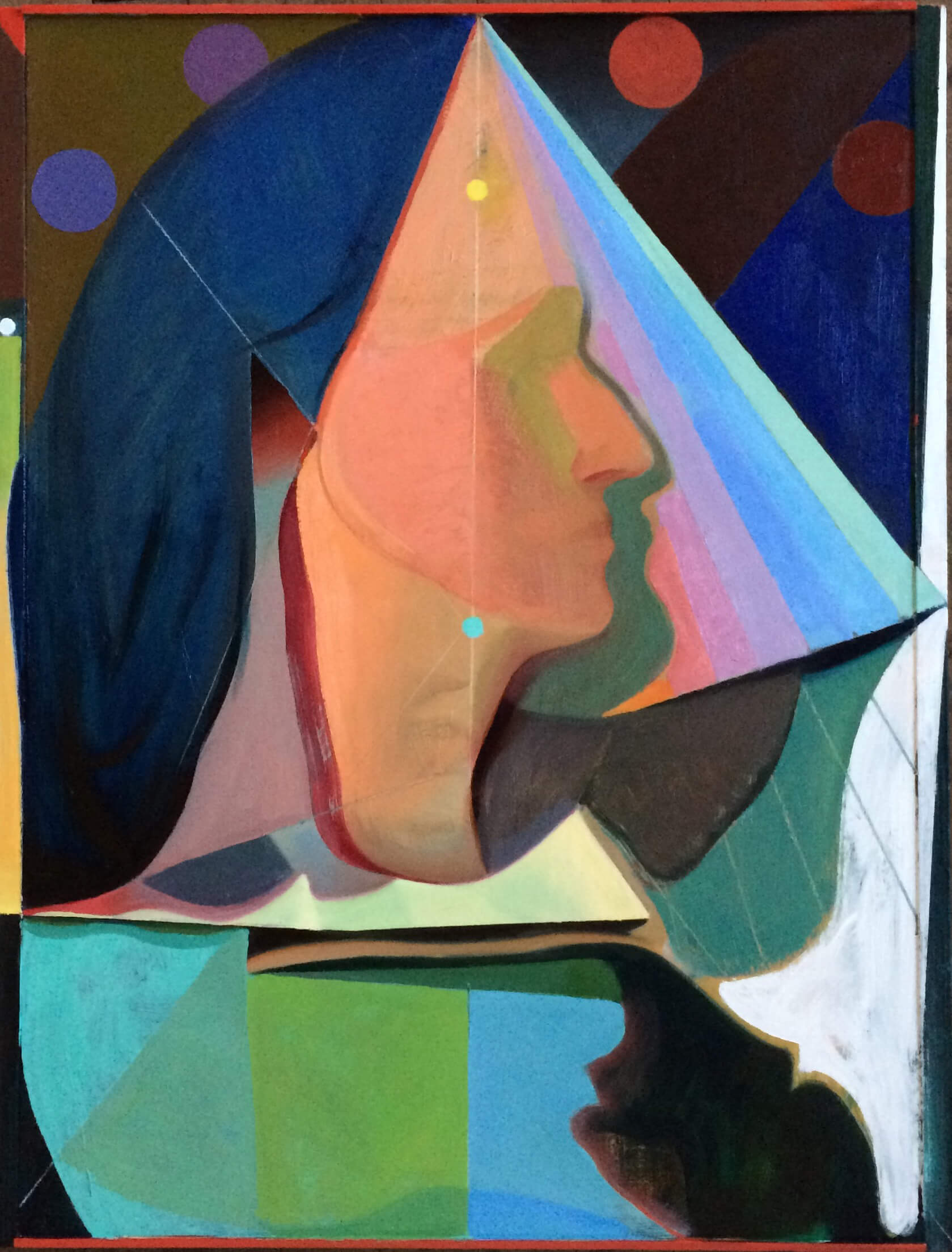

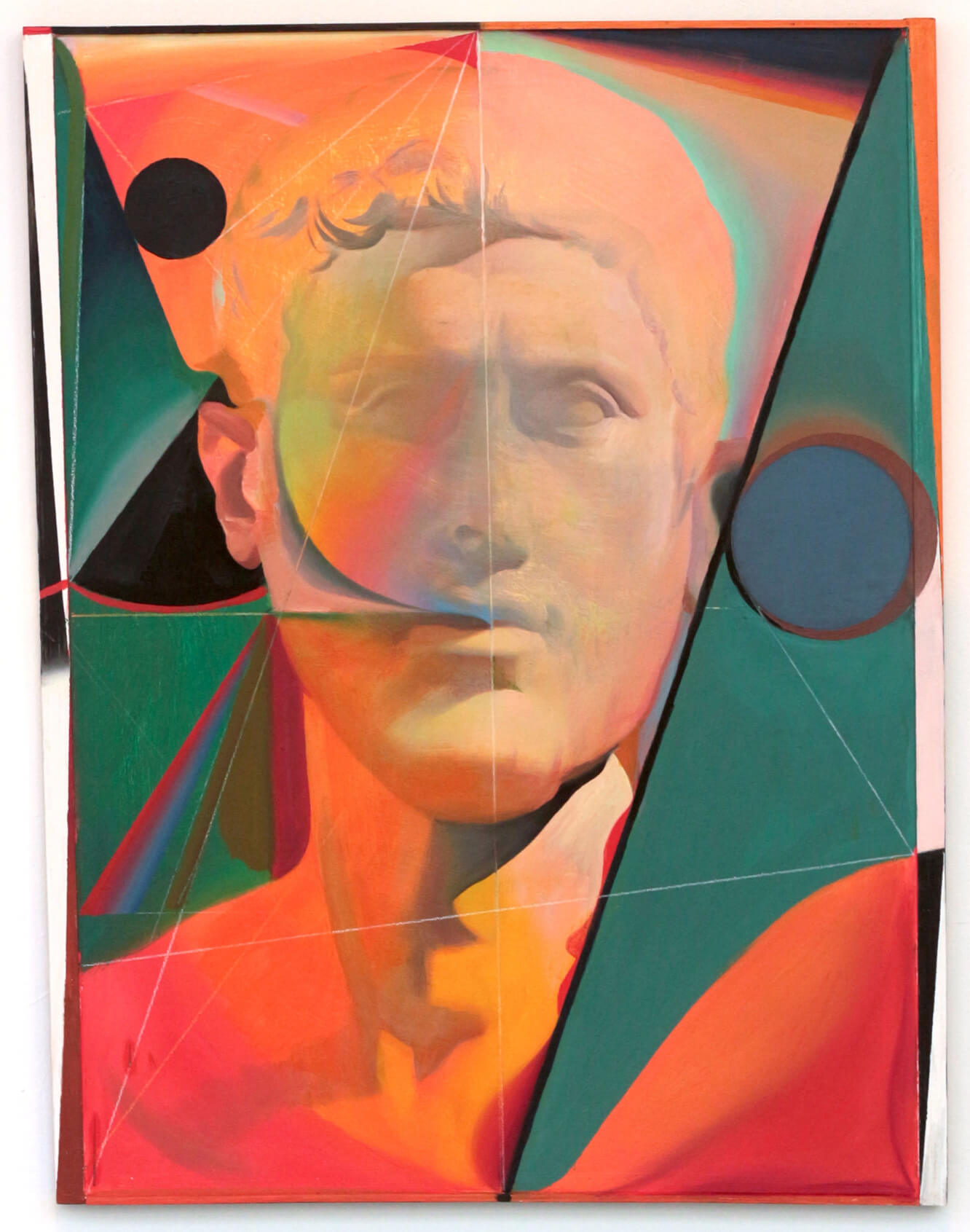

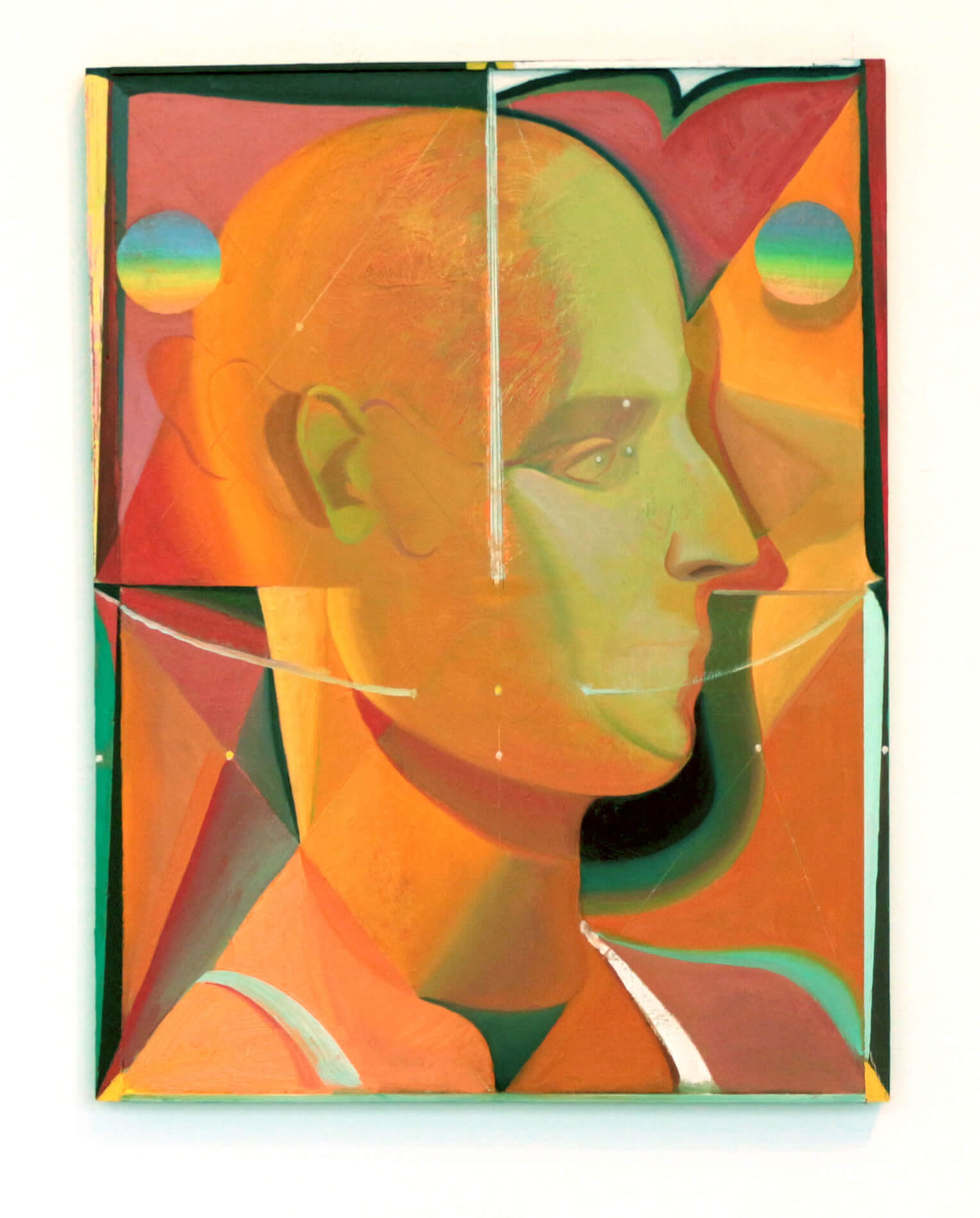

In the “Portraits of Scientists” I decided it was important to think more carefully about the painting and image as being “constructed.” The panels I paint on are designed to promote compositional interaction with sculptural edges and framing devices. These are small shelves that line the edges of the panel at different subtle reliefs. The images themselves are meant to present a mystical and or analytical version of an image of a head. The features of the face and the contours that describe its dimensions drift across the picture plane or arrange themselves into some other guise like objects on shelves or quick handwriting. Some of the heads begin with historic precedents, some are my wife, and some are notations from my imagination. I add geometric elements like lines and circles to divide and separate in a way that makes the spaces more tangible. It’s a work in progress, but it has been exciting to wrestle with.

People talk about drawing as the most immediate art form. I think of perceptual painting (especially in the landscape) as an immediate and responsive way to paint. I bring students to Italy every year, and most of them have never painted. It is amazing to see how naturally the simple materials conduct themselves in a world of light and air…

Perceptual painting requires you to be present. It only produces interesting results if you can believe in the beauty and power of what you are seeing. I love this idea! I paint from life regularly to practice that kind of mindfulness. It’s like building up experiential energy and storing it in your memory so that when you paint from your mind you imagine in a way that is vivid. This doesn’t mean perfect shape and detail of things recollected (at least for me), it means a certain type of presence and intensity. In addition the surprise and continuity of color systems in nature teach you how to move from color to color- how to organize tones and the key of a painting.