I went back to my own idioms, envisioned, created, and thought through. And the insight and the momentum established altered the character of the whole concept of the practice of painting. – Clyfford Still 1

The Clyfford Still Museum’s inaugural exhibition provides new insight into the development of Clyfford Still’s groundbreaking abstract paintings. In addition to rarely seen early landscapes and early figure paintings, a gallery of never before seen works on paper reveals the process behind Still’s visionary work. Though only a small selection of Still’s 1,500 drawings are on view, they reflect a practice of lifelong visual inquiry and show drawing to be an important, perhaps crucial, tool in Still’s dramatic evolution from regional artist to icon of the New York School.

Still’s transformation from a regional painter of the pacific northwest to a celebrated avant-garde artist has, until now, seemed uncanny. The shocking way Still’s paintings fused figure and ground so completely left his 1940s contemporaries (as well as art historians) flummoxed and awe-struck. His 1946 show at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century Gallery was, in Robert Motherwell’s words, “the most original. A bolt out of the blue. Most of us were still working through images… Still had none.” 2

Still’s works on paper suggest the key to his originality lay in his willingness to explore, test, and reflect upon his vision. Still’s drawings contain clues to his initial motivations and to what interested him within his own work. In them, we also see Still as an artist committed to direct observation and investigation. A traditional approach, it seems, provided the starting point for Still’s innovation.

An early study of a seated nude demonstrates not only Still’s ability to render forms accurately but also his attentiveness to the planes of light and shadow that define the figure. Given his later achievement of merging figure and ground, this early evidence of sensitivity to planar shifts in light and dark is unsurprising. It does, however, convincingly trace Still’s deft manipulation of figure and ground back to observation. To see Still engaged in drawing from a life model, a basic academic exercise, lends new irony to Pollock’s later comment that “Still makes the rest of us look academic.” 3 It it also dispels the notion that Still’s radical visual language owed its origins to a lack of technical facility. 4

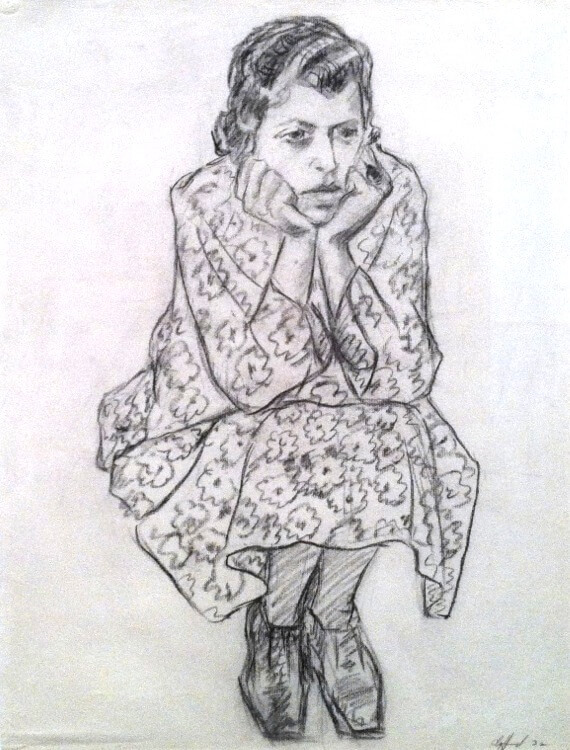

An adjacent, engaging portrait of a girl seated with her elbows on her knees shows Still again working from life. His interest seems piqued by her pose – her arms and legs are folded into her body, her elbows resting on her knees, and her head held in her hands. He draws her limbs and dress as one, rendering them together in an inventive series of jagged lines, while the “all-over” print pattern of her dress further flattens the image into an arrangement of compact, tectonic shapes.

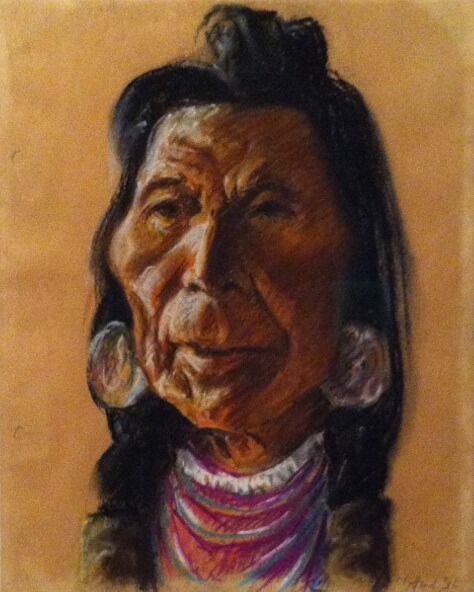

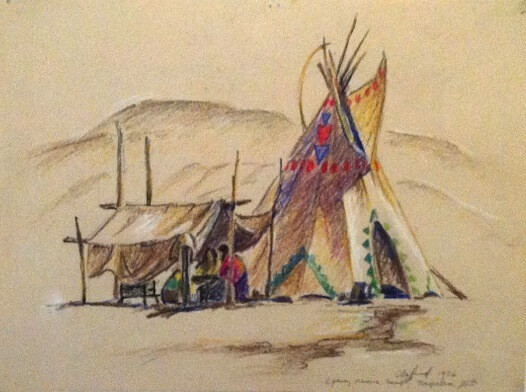

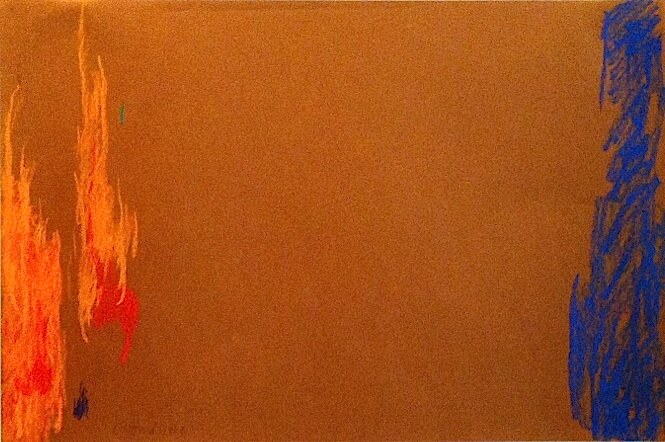

Another striking portrait is a pastel of a Native American whose face is furrowed by age and hardship. This drawing serves as a realist foil to the many mask-like faces in Still’s paintings from the 1930s. Above this drawing to the left hangs a rapidly sketched, colorful shawl notated with just a few marks. An array of bright colors against a neutral background, it presages the spare oil paintings Still painted in the 1970s. Below the shawl is a simple landscape drawing with a teepee and shelter in the foreground. This unassuming drawing, a travel sketch, is one of an artist inclined to record his surroundings. To see that Still, infamous for his unwaveringly high sense of purpose, valued matter of fact notation is refreshing. Hung as a suite, these three drawings effectively demonstrate how Still used drawing as a tool to feed his repertoire of increasingly abstract images and marks with fresh visual information.

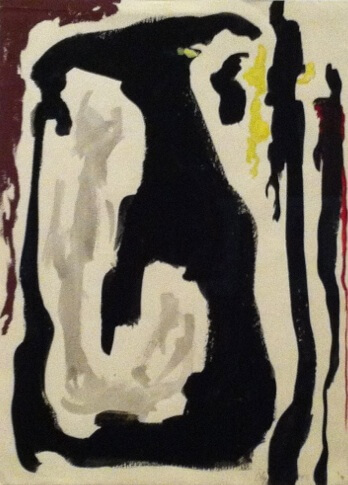

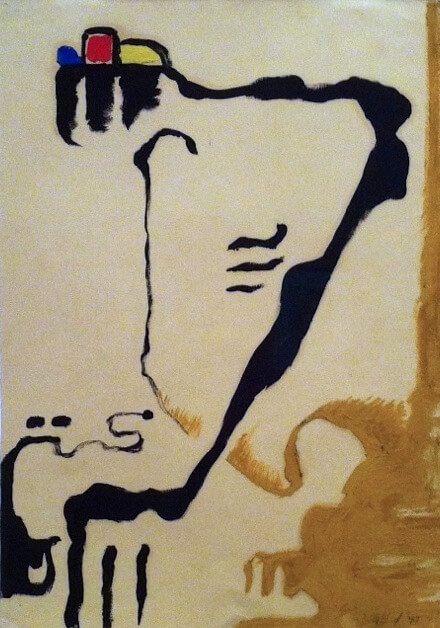

A long wall of drawings in oil paint from 1943 are the most exhilarating in the exhibition. That Still achieved his full maturity during the period when these drawings were made while he was teaching in Richmond, Virginia, is well documented. 5 Still’s time in Virginia set him on the path that would shock and awe visitors to the Art of This Century Gallery and solidify his position as a leading Abstract Expressionist painter. These works in oil on paper show Still considering and working through an increasingly personal vocabulary of forms.

Each piece seems part of a continuum of thought, and in variation after variation, Still lets his new forms morph freely across the sheets which offer no resistance to his racing mind. The fluidity and freedom of the group suggests they were done one after another after another. They are exciting to see, like frames from a film, and clearly show Still speeding closer to pure abstraction. They are deft, sure, and ecstatic and do much to reinforce Still’s contention that his work was a source of “joy.” 6 More importantly, they show the practice behind the certainty of Still’s large paintings.

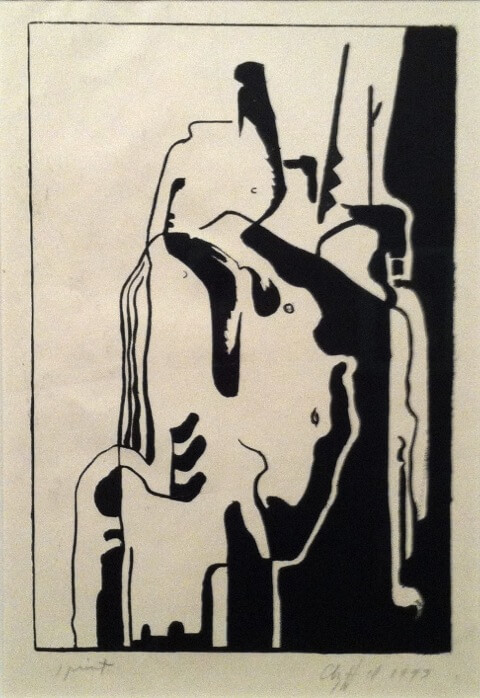

A group of lithographs hangs opposite the oil studies. Done “after” specific paintings, they serve more than a documentary function; they show Still using drawing to study his own work as he studied the world. In them, Still teases out and simplifies the forms in the paintings. Through this simplification, we can see him working toward the final merging of figure and ground. His working “after” method, shown here, may also shed new light on his controversial practice of creating “replicas” of his own works, supporting his statement that this practice served to “clarify and refine.” 7

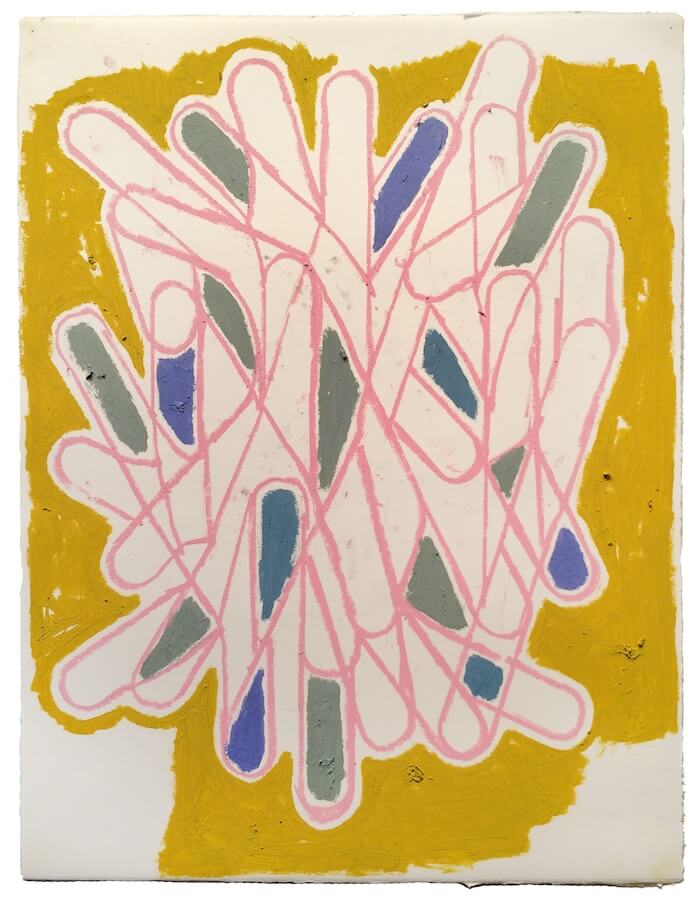

The majority of the later works on paper in the exhibition are pastels. Though his use of pastel was evidently lifelong, Still completed around 1000 such pieces in the 1970s. 8 His technical mastery of the medium is evident, and the examples on view show Still using a range of touch and often working on colored paper. Many feel like studies, perhaps done concurrently with paintings, that investigate possibilities and variations. In them Still tests amounts of color and horizontal divisions of space. He also employs a wide range of mark, from short spark-like strokes to velvety clouds. He experiments with color as well, including a primavera palette of ochres, turquoise, and lavender – colors that appear infrequently in Still’s oil paintings.

As in some of his best oil paintings, however, black holds sway in the strongest pastels such as PP 43, 1959. Still moves well beyond a study in this work where a blanket of warm blacks enfold an area of deep purple. Across a gray field, a tenuously vibrating white filament creates a compelling counterpoint.

The Clyfford Still museum has introduced a rich, hidden history of one of our most important painters. Still’s works on paper reinforce the notion that originality is achieved through attentiveness to the world as well as one’s own vision. They suggest genuine originality isn’t possible with one or the other – it needs both.

Notes

1 Clyfford Still quoted in Patricia Still, Clyfford Still: Biography, Clyfford Still, 1904-1980 The Buffalo and San Francisco Collections, pp. 114.

2 Dean Sobel, Why a Clyfford Still Museum?, Clyfford Still Museum Inaugural Publication, p. 31.

3 Ibid, p. 31.

4 John Golding, Newman, Rothko, Still and the Reductive Image, Paths to the Absolute, p. 153. Golding writes that “It says a lot about the nature of abstraction that it was the vision of these artists and not their natural gifts that enabled them to turn themselves into great artists.”

5 Still’s productivity during this period is acknowledged by Sobel (p. 23) and described in detail in Thomas Kellein, Approaching the Art of Clyfford Still, Clyfford Still, 1904-1980 The Buffalo and San Francisco Collections, pp. 16-17.

6 “A great free joy surges through me when I work.” Clyfford Still quoted in Neal Benezra, Clyfford Still’s Replicas, Clyfford Still Paintings 1944 -1960, p. 87.

7 “There have been occasions when I have painted, deliberately, replicas… to clarify or refine a specific work.” Ibid, p. 92.

8 Sobel, p. 37