Eight Painters

Curated by Paul Behnke

Kathryn Markel Fine Arts, New York

January 4, 2014 – February 1, 2014

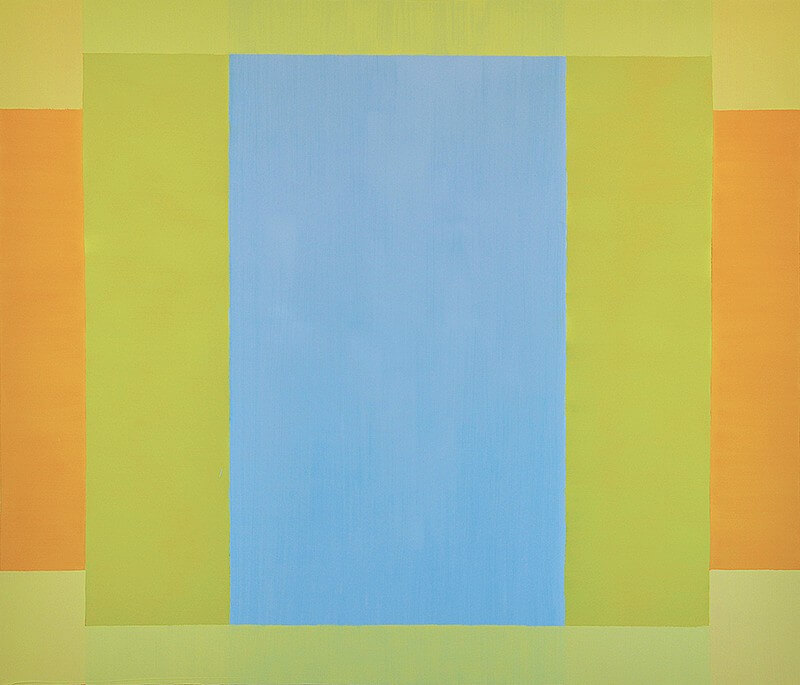

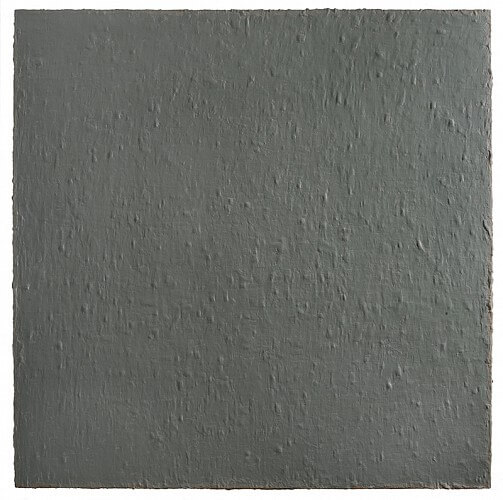

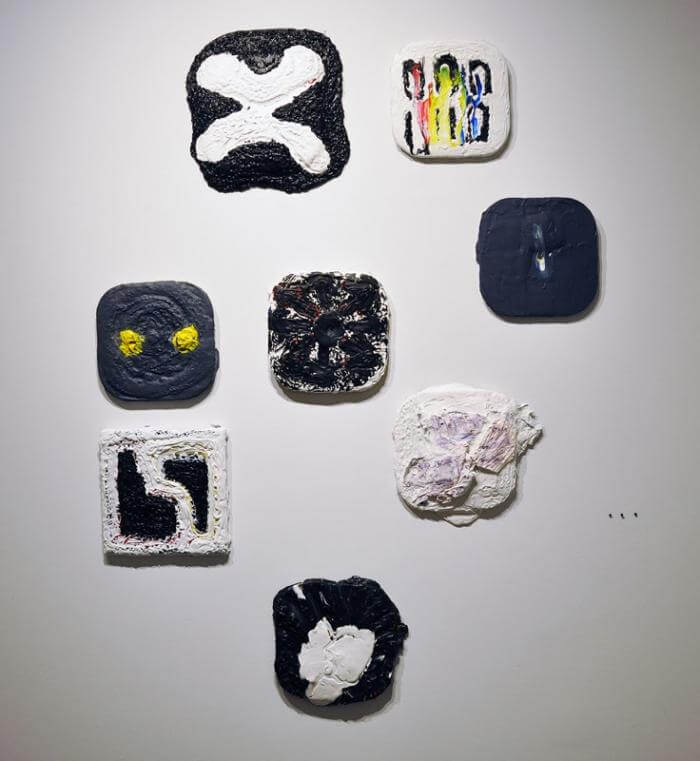

Featuring paintings by Karen Baumeister, Paul Behnke, Karl Bielik, James Erikson, Matthew Neil Gehring, Dale McNeil, Brooke Moyse, and Julie Torres.

Paul Behnke’s curatorial criteria for the show Eight Painters are compellingly straightforward: “an individual, rigorous vision; a certain ambition without regard for scale or a specific way of making a painting; and an abiding belief in the ability of paint – and specifically, the genre of abstraction – to best communicate the artist’s appetite and inventiveness.”

In other words, the show features painters deeply engaged with the medium of paint. It’s a powerfully simple premise. Eschwing trends and labels, the tools of the art market, Behnke puts the focus where it should be – on the paintings themselves. He generously agreed to discuss the show with Painters’ Table. —Brett Baker

Painters’ Table (PT): Your decision not to organize the show around a visual “theme” is uncommon these days – even somewhat radical. Can you expand a bit on how you came to believe that the commitment of each artist to the internal language of their work was the most worthy organizing principle?

Paul Benke (PB): I think as a painter I’ve always felt this.

Recently, the predominant way that paintings have been presented and viewed has been in the context of a curatorial theme. The more in depth statement of the one person exhibit is being pushed aside in favor of a “hook” that I think art spaces feel they need to draw in viewers. These curatorial themes start to seem necessary to make painting feel relevant. To submit a body of work to almost any art space’s open call you must have a “project”, a hook, and it’s even better if your idea involves some sort of play on Relational Esthetics or is community based. All of these approaches have their place but this type of exhibition has become prevalent at the expense of a deeper, more encompassing experience of the painter’s work.

Good painting is as varied and multi-layered as the person who made it. Thoughts, memories, visual associations – the sum of a painter’s daily life – personality and experiences feed into a work. And that’s just the conceptual content. To say nothing of the subtleties or boldness of a paintings formal qualities and the staggering number of decisions that go into realizing a piece. To reduce all of that to a fragment of its intent runs the risk of doing the medium and painter a disservice, especially if the viewer is easily swayed or lazy.

I did what I could to negate this approach in Eight Painters. I intentionally kept the number of exhibiting artists under ten and asked for one piece or a concise grouping of work from each. I wanted something closer in feel to a museum display rather than an over-hung, chaotic presentation. Within those parameters I felt I had the best chance of giving the work, the painter and the viewer the kind of experience they deserved.

PT: The title of your essay for the show catalogue is “The Ability of Paint.” It’s a beautiful thought in and of itself, suggesting painting possesses (and always will) an innate capacity for cultural accomplishment. What accomplishments remain for painting in your opinion?

PB: In a way I resent that painters and the medium are burdened with ideas of cultural accomplishment. It seems we lay this task at painting’s doorstep more so than any other medium or creative endeavor.

That being said, I’m not sure what else painting can accomplish or needs to. I’m not sure any medium will ever be able to change the way we look at the world around us the way paint did in the hands of Seurat, Cezanne, Braque, af Klint, or Pollock.

But paint can still be a means of deep connection between the painter and the viewer in the same way poetry forges a personal connection. It is a way to make the artist’s experience real and compelling, and when this is accomplished in partnership with a kindred audience that’s all the accomplishment that’s required. To do this, today, is more than enough.

PT: You also acknowledge in the essay the acceptance of a certain iconoclasm, a willingness on the part of the artists to make objects that risk obscurity by refusing to cater to a culture defined by technological advance. You even go as far as to suggest that viewers “must be susceptible” to appreciate the “full power and subtleties” of the work.

PB: Yes, painting isn’t for everyone. I see painting, today, as a radical act. And despite what we see, in our corner of the art world in Bushwick at the moment, the type of visual experience that abstract painting provides seems to be less in demand. But this is true with many good and important things. Poetry and Jazz are two. That doesn’t mean that these things aren’t vital or shouldn’t be valued. Of course they should.

Look, painting is difficult and it requires effort of the viewer. It requires work and enough interest and curiosity in what you are looking at to go out of your way and to invest something of yourself.

Luckily, there are viewers out there who are susceptible and open and hungry for the power, subtleties, and connection that abstract paintings offer. And even more importantly, there are many, many artists who are drawn to paint and feel that it best conveys their intention and vision.

PT: Although each artist in the show has been selected for the individuality of their approach, they all make abstract paintings. There is an implicit enthusiasm for abstract painting in your selections. Not everyone would agree that abstract painting merits the popularity it currently enjoys. Holland Cotter, for instance, was disparaging of abstract painting in a recent article, condemning it for the supposed ease with which it can be experienced online – one of the very reasons you champion it in this show.

PB: Holland Cotter is obviously not a painter. And that article makes me question his sensitivity and his ability to effectively write about painting. His view couldn’t be farther from my experience. I’m in daily contact with abstract painters who are deeply committed to their medium and to abstraction. We believe in paint and devote countless hours and money and mental energy to it, often with little or no return. But it gives our lives meaning.

I think critics like Cotter (in this instance) and Saltz (in many) spend too much time and ink bemoaning the vacuity of the art and artists presented in Blue Chip spaces and too little time outside the borough of Manhattan writing about artists and galleries that make and show sincere, good, and genuine work because they have to.

Thankfully, in Brooklyn, painters have been able to count on the support of champions like John Yau (Hyperallergic Weekend), James Panero (The New Criterion), and Michael David (painter and Director of Life on Mars Gallery) and some others.

I think the resurgence of abstract painting reflects dissatisfaction with our machine made, instant gratification culture. There will always be a segment of the population no matter how small that values the hand made and the slow.

Whether abstraction is in or out of favor has nothing to do with my work’s trajectory or the work of the others in Eight Painters. Worrying about trends or what the larger art world and market are doing or valuing is like obsessing about the events of a party that I was not invited to. What people do there has no bearing on my life or the kind of work I make.

Abstract painting is in the blood and luckily, so far, I’ve found no shortage of relatives.