Life in Death: Still Lifes and Select Masterworks of Chaim Soutine

Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York

April 2014

The 1950 Chaim Soutine retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art was arguably the most influential museum exhibition of that decade. Numerous artists, including Willem De Kooning, Jack Tworkov, and Milton Resnick, found in Soutine’s paintings the “qualities of composition” and “attitudes towards paint” they were wrestling with in their own work. 1 Perhaps more importantly, Soutine connected their concerns with the tradition of western art, something particularly important to de Kooning. 2

Despite his clear impact on New York School painters, art history has been especially two-faced when it comes to Soutine; nearly every critic of his work feels obligated to gush about his unparalleled abilities before pointing out that Soutine’s achievements were the wrong ones at the wrong time. What Soutine stood for – the power of painting to derive essential truths through direct contact with nature – was at odds with modernism, which increasingly privileged artifice and irony over nature. Reviewing the 1950 MoMA show, Clement Greenberg observed (solemnly and with the utmost regret) that Soutine pursued an expression “more like life itself than visual art.”

Although museums like MoMA (who not long ago deaccessioned a Soutine painting) may be severing their ties with Soutine, Chelsea galleries have given viewers and opportunity to see his work in recent years. This past summer, a modest, yet riveting selection of paintings by Soutine was on view at Paul Kasmin Gallery. The Kasmin show not only highlighted the artist’s feverish dedication to “sensations-in-paint,” (Andrew Forge) but also helped clarify the artist’s distance from, and perhaps disdain for, the artistic approaches of his contemporaries and the succession of ephemeral movements that comprised modern art.

With brush in hand, Soutine charges headlong at the world; he is willing to risk being overwhelmed. His intensity is ultimately overrun by the reality he seeks, but he stands his ground just long enough to create a moment for us to see things as they are.

This intensity was particularly evident in the Kasmin show in Landscape at Céret (c. 1922-23), in which Soutine succeeds at holding his own in the midst of an uncontrollable, whirling nature. There’s no composing in this picture, no balancing of elements – there is simply the rush of paint, a direct response to the ordering attention of the eye. The entire composition of Table with Skinned Rabbit (c. 1923) is ordered by the struggle of flesh in a twist of decay that warps and strangles everything around it.

In Hare with Forks (c. 1924), Soutine indulges in an obvious metaphor for his own obsessive approach. He, like the forks, is a type of predator, ready to tear open the reality before him to see whether the nourishment of a greater reality exists beneath. The melodrama of the motif is relieved by the variety of attack and completeness of realization. Up close the roving brushwork is a gestural map of visual attention; from a distance, the exactitude of the spatial description echoes the plight of the subject, the table cloth is stretched to its limits in sympathy with the hare.

Although no painting in the Kasmin show disappointed, several pictures faltered in comparison to the best works for various reasons. The extra wide format of The Rainbow, Céret (c. 1920), for example, proves too expansive a surface to apply to, or receive pressure from, the forms within. Likewise, the passage of red, intended to hold the left foreground, fails to provide chromatic structure. Yet the painting has spectacular moments: the ravine between two houses on the right plunges, squeezing space, and the light-filled clearing near dead center surprises in the clarity of its spatial hollow.

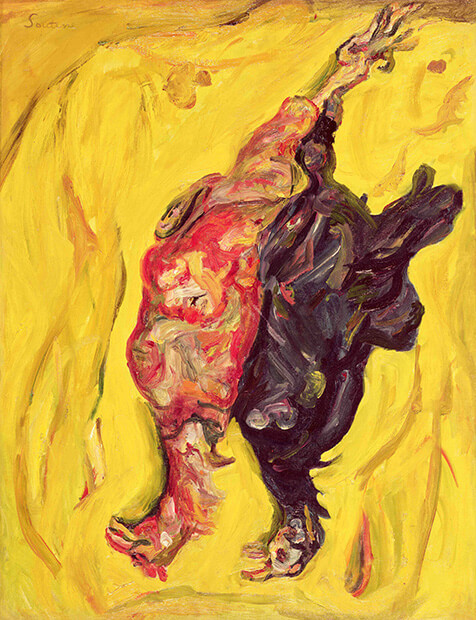

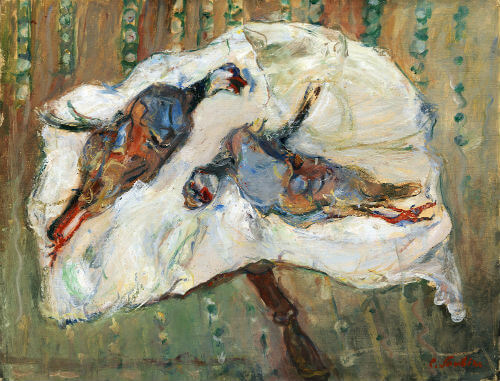

Soutine also seems less engaged with more standard still life arrangements, such as Still Life with Fruit (c. 1919), than he does when painting dead animals. He is at his best in works such as Plucked Goose (1932–33) and Two Pheasants on a Table (c. 1926). He clearly finds his true purpose in pathos. When Chardin paints a dead fowl, we feel the brokenness of its form as if we could reach out and touch it. When Soutine does the same, we feel the brokenness even more vividly; we clutch the limp, fading warmth as if we ourselves had done the breaking (we must then wonder how we might feel about that).

Hung in the darker back gallery are the earliest and latest paintings in the show. The former, Landscape with Donkey (c. 1918), shows Soutine working through a more geometric structure informed by cubism. The lively undulating foliage seems to call on him to renounce the cubist trope of the red roofs, one can almost hear nature whispering in his ear to do away with the ridiculous “little cubes.” A small red donkey anchors the left bottom corner of the painting signifying, perhaps, both the ineptitude of more intellectualized approaches to painting and a longing for a return to simple basic instincts.

If Soutine’s late paintings (as is often argued) are products of diminishing intensity, Maternity (1942) fails to make that case. The nervous mother stares blankly, overwhelmed by the shock of her new responsibility. Her child is splayed across her lap, a malleable, tenuous form that may either thrive or slip away. The paint of the woman’s lap surrounding the child reads as shadow but also emphatically remains a swath of paint. This inchoate potential clearly weighs on the mother. She is paralyzed, it seems, with the realization that, having given birth, she is now also charged with forming a life. While the mother is rendered in warm tones, the child in her care is illuminated by the coldness of fate.

The shifting light that filtered through the skylights at Kasmin gallery was a fitting reminder of the vital, yet fleeting quality of life that Soutine attempted to grasp. One sees that Soutine achieved the “slipping glimpse” that informed and inspired the work of de Kooning. It was during the run of the 1950 Soutine retrospective that de Kooning threw himself into the painting that would become Woman I (1950-52). One hopes that more than a few contemporary artists who visited the Kasmin show are similarly energized and moved, perhaps, to once again create art that is “more like life.”

Notes

1 Jack Tworkov quoted in Soutine and Modern Art, Cheim & Read, 2006.

2 Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, de Kooning: An American Master, 2004, p. 312.