Babie Brood: Small Paintings and New Paintings

David Zwirner Gallery, New York

November 8 – December 15, 2018

Uptown, Lisa Yuskavage’s large paintings adorn a grand brownstone the tony couples she depicts, exuding comfort in their uncomplicated skin, might live in. Powerful impulse and hand are instead featured in the retrospective of small paintings downtown, where scores of artfully clueless babes splayed across huge walls uncomfortably cue feminism.

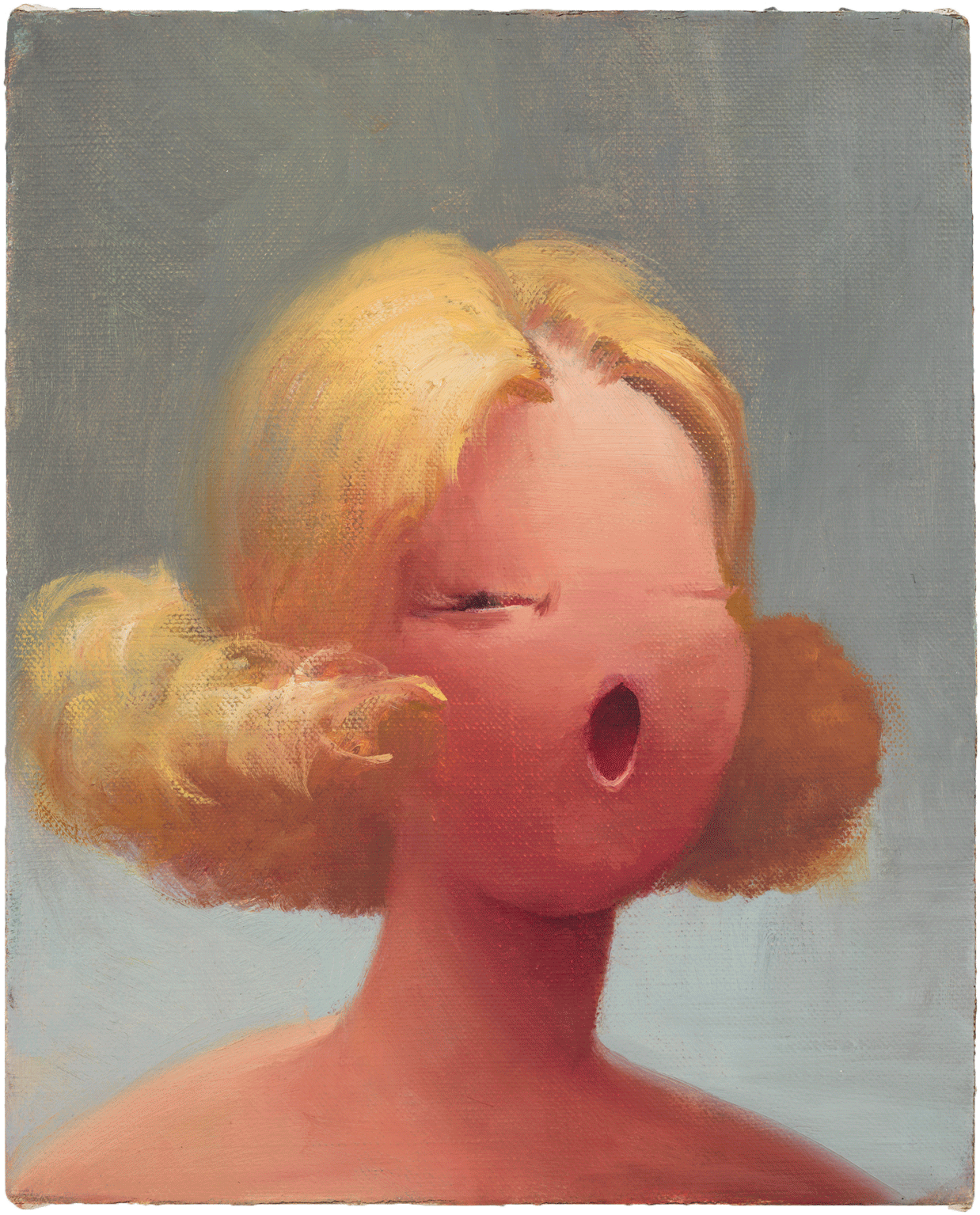

Yuskavage’s early figures, like John Currin’s, smartly deferred to minimalism as the figure, shamed for dubious political collusions during the Cold War, reentered the New York centered art world. The compliant, open-mouthed “Oh” is a Betty Boop cum blow up doll. As usual, dark humor and acrid color are mitigated by luminosity and sensitive execution. Specific yet shorthand rendering lets tightly closed eyes suggest invisible raised eyebrows and a subtle wince. Mirror neurons fire as the brush touches tresses, conjuring memories of grooming dolls. Aggression is feminized as form turns soft, round, and pink.

Women have been painting women in earnest only since The Pill bequeathed leisure time, but the female form has been represented at least since paleolithic sculpture as mother, goddess or occasional ruler. After Greek realism was applied to Christian iconography, women in western painting abounded. Spiritual purity versus earthy detail embodied contrasts of nude and naked in representations of the Madonna, her wayward ancestor Eve, and various saints masochistically imitating Christ’s self-sacrifice.

Like those archetypes, Yuskavage’s females fall short of self-awareness. “KK” approaches it, without reaching the existential cusp of Munch’s “Puberty”. Like Eve post-Eden, she turns away from her nakedness but keeps a sharp eye on the viewer. Rembrandt-like chiaroscuro grants her both prospect and refuge from the protective shadow which flattens toward the picture plane like a shield.

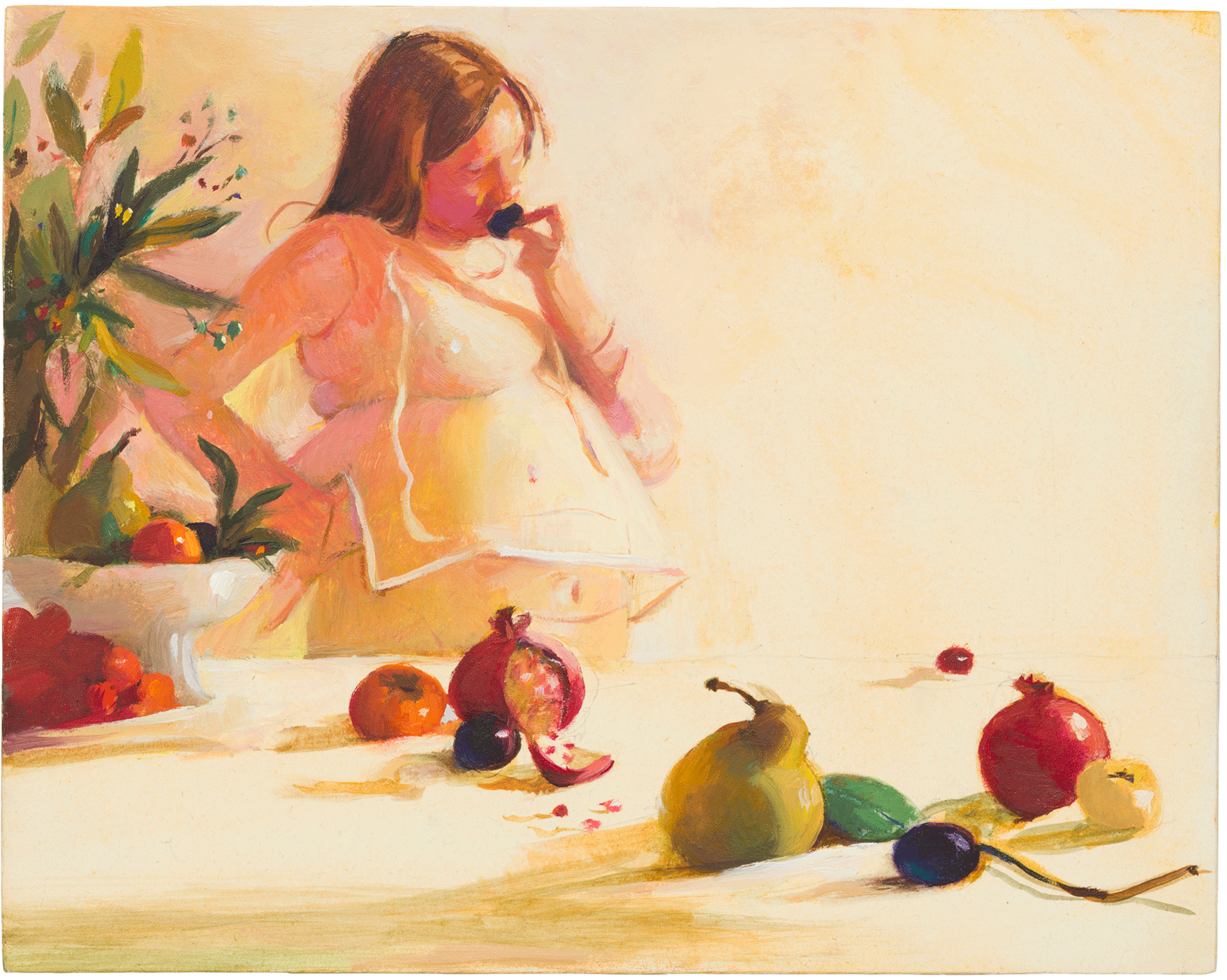

Yuskavage’s oblivious females are masterfully directed by light’s evocations, from sinister to cheerful. In “Small Morning” a pregnant and/or chubby young woman innocently eats small fruit behind a histrionic still life with portentous long shadows, light illuminating all but her perception.

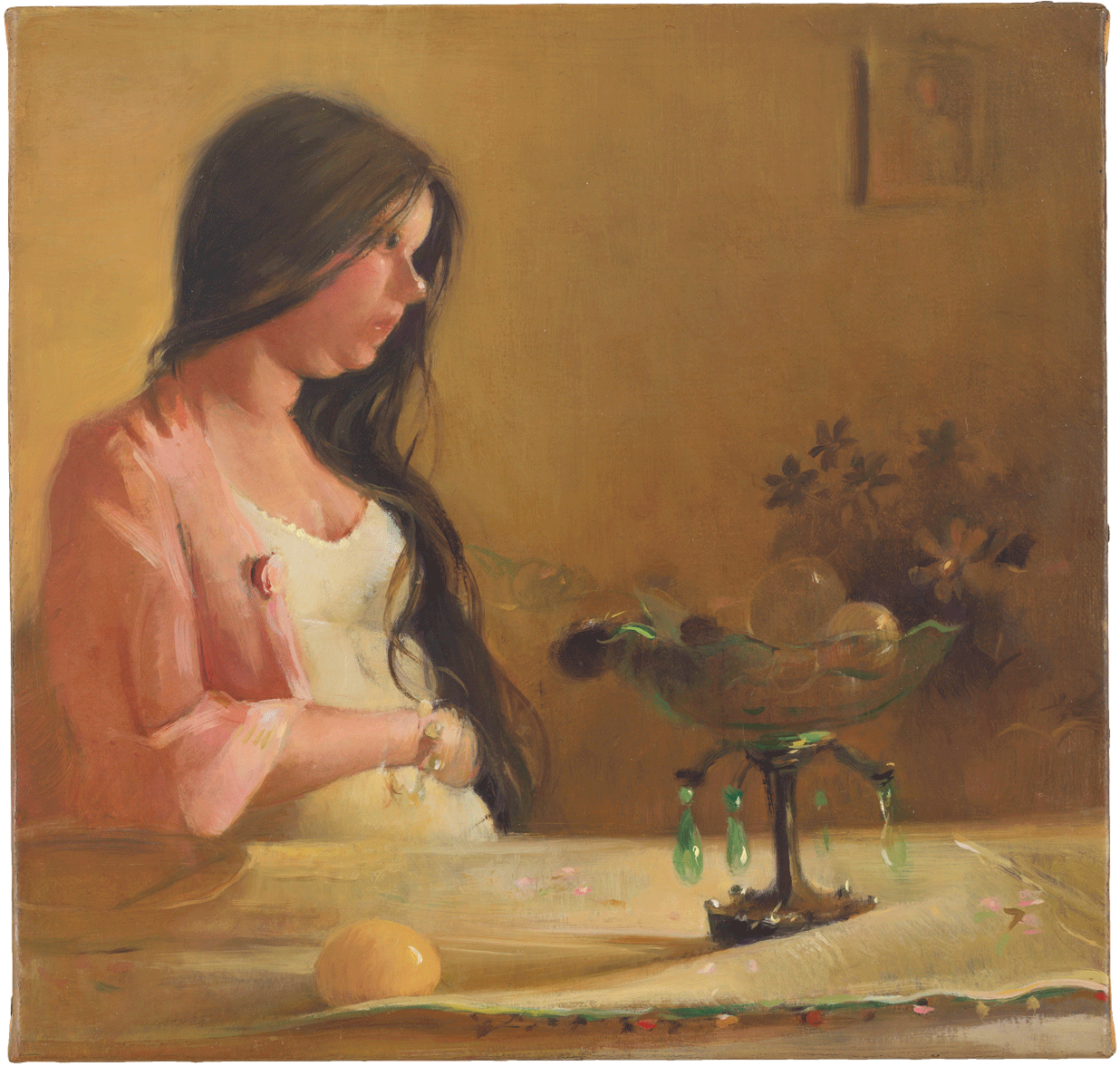

“Wee Morning” resembles De la Tour’s “Penitent Magdalene” but lacks that character’s sin-grappling depth. Haloed in expectant light, she is both virginal and daffy, too descriptive to be an unquestionable icon, too cartoony to think for herself. Michael Baxandall in “Painting and Experience in 15th c. Italy” explained the proto-psychological stages that annunciations put Mary through. A spectrum of female reaction was acknowledged – disquiet, reflection, inquiry, submission, merit – yet Gabriel’s offer could not be refused.

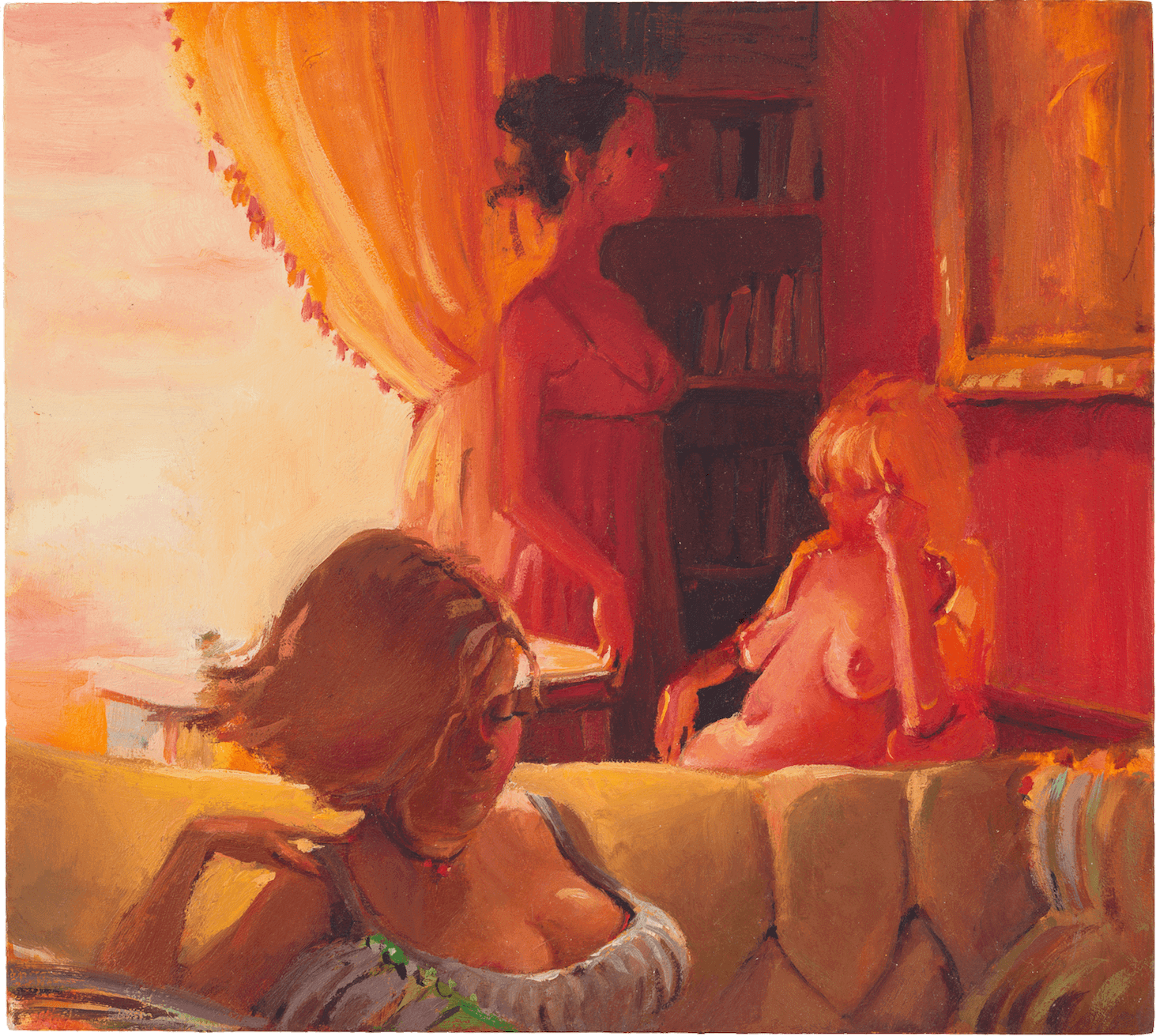

Yuskavage’s girls similarly lack agency, people pleasers who can’t help but expose themselves. Slivers of cognizance repeatedly fail to launch from the Id. Flagrantly acting out artistic whim, they are like Cindy Sherman’s females eternally stuck as objects of the gaze. Another unnecessarily dramatic (and thus humorous) deep space in “Northview Afternoon” contains a buxom blonde lounging in the foreground, probably leafing through “Vogue.” Behind her another relaxes in inappropriate toplessness, her mysterious self-possession nearing that of a devotional figure or classical nude. A girl passing by in back notes the viewer with mere deer-like vigilance.

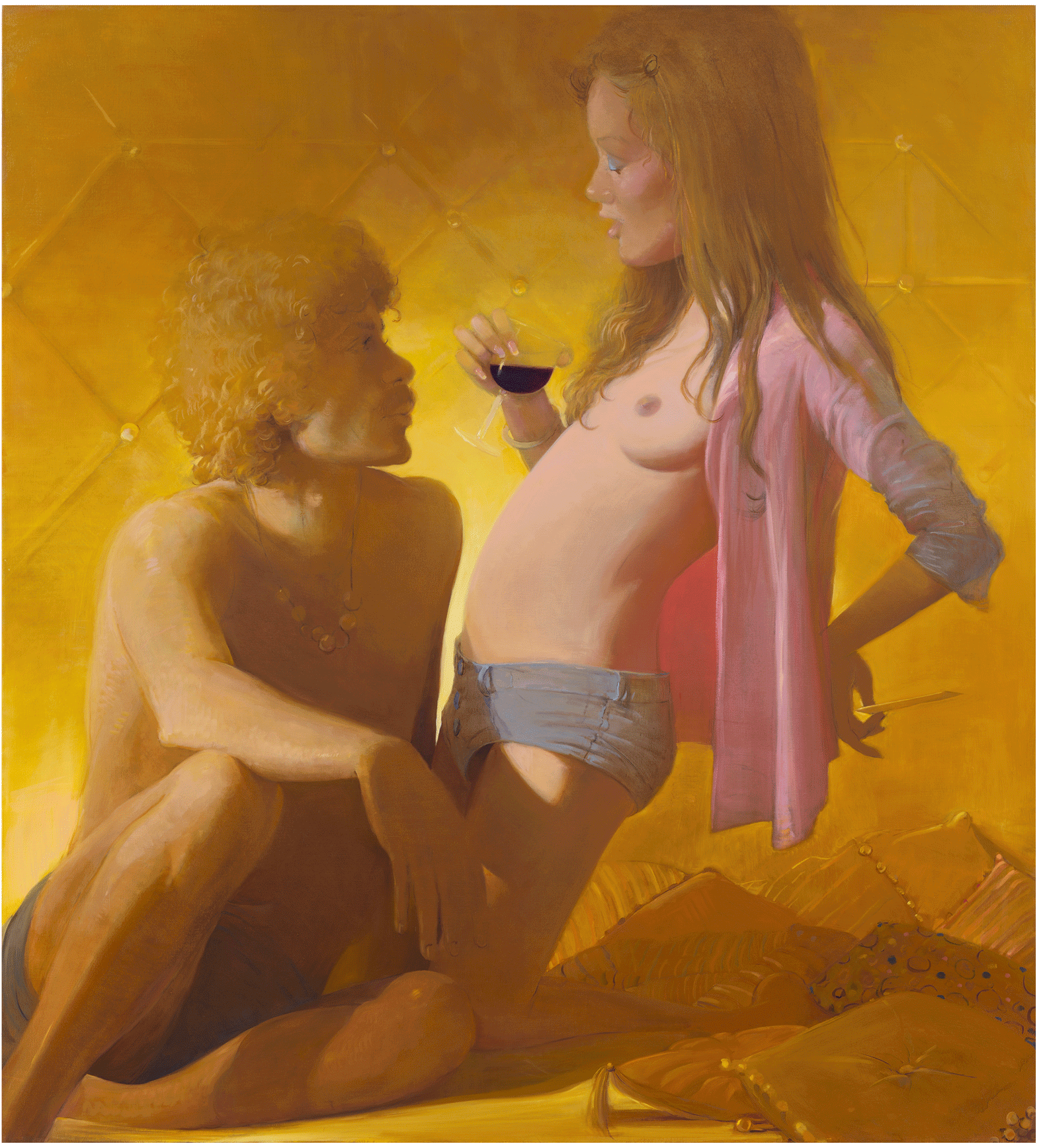

Yuskavage’s jaundiced eye is gender blind, as the more reasonably painted uptown work shows. Jokes go more formal, like the wedge of strong yellow bracing an impossibly leaning half-naked and assertive young woman in “Golden Couple,” who could be explaining feminism to her attentive companion between sips of wine.

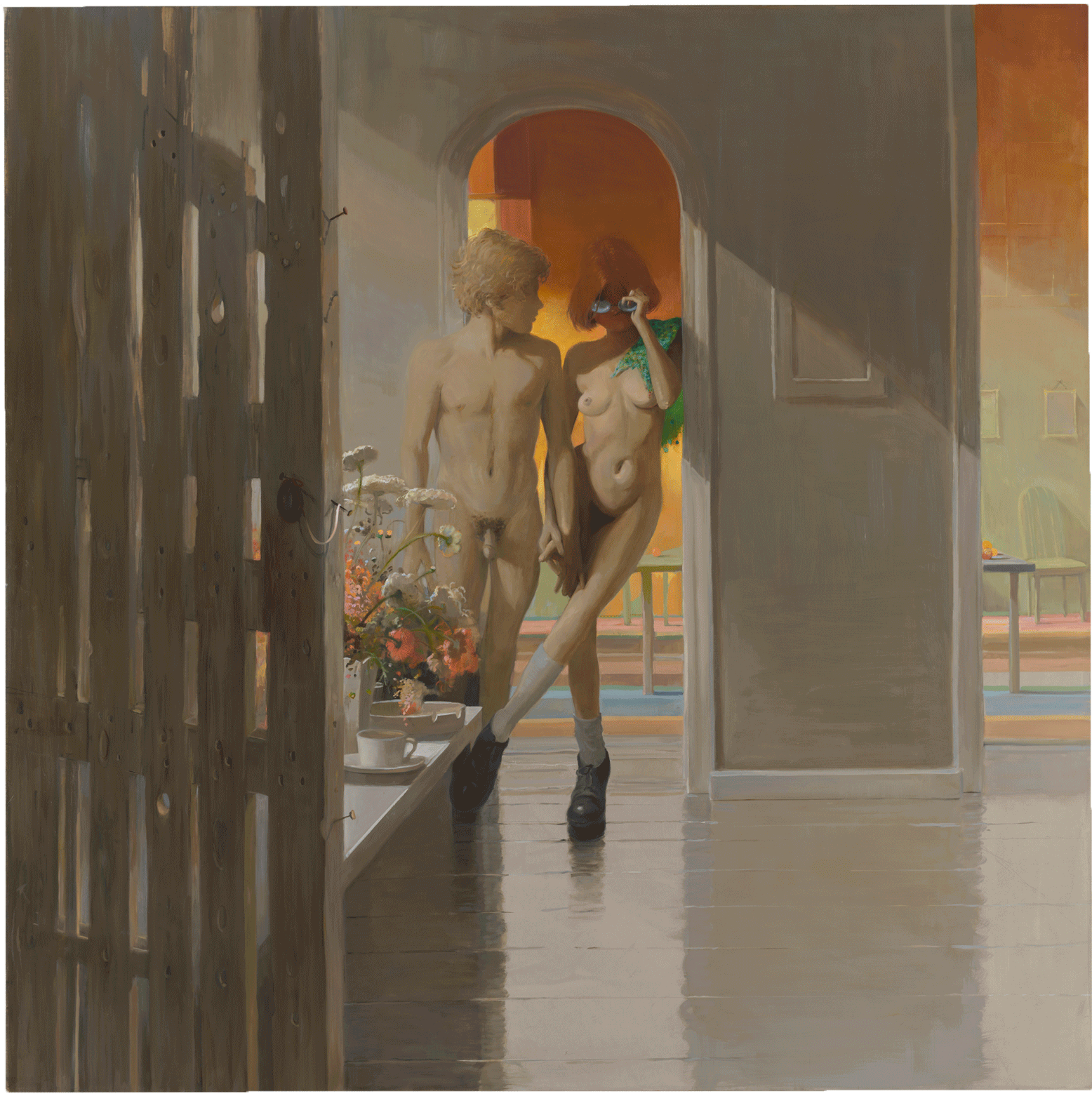

Like an Adam and Eve who evaded a Fall, the Abercrombie-ish couple in “Home” advertise a rustic chic lifestyle, she with a casual fierceness, he with metrosexual contentment. Sarcasm is offset by particular, light-wrought textures.

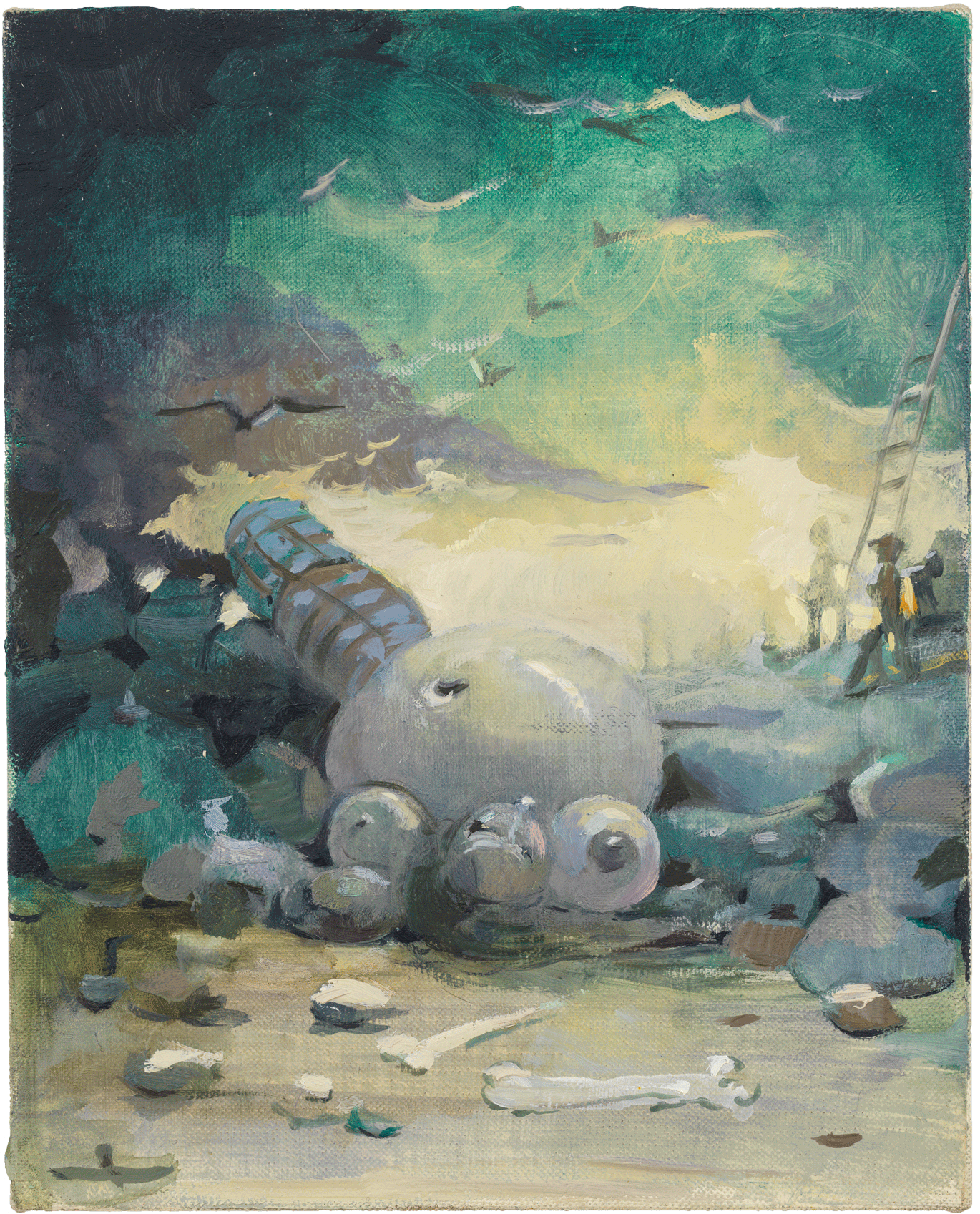

In the small, diaristic works Yuskavage shows more of her hand, in both senses. In the cruel, clever “Ditch” a foreshortened female lies bloated, about to give birth alone in the desperate, bone-strewn landscape, or maybe just digesting cannibalized competitors. Brushwork tracks nuances of the painter’s emotions and imagination in action. Gentle veils of color hover over the pathetic protagonist almost apologetically, leaving hope on the horizon. Atmosphere provides informed context, expressing circumspection her figures lack.

As religious iconography went out of fashion, 19th c. painting’s females adopted ordinary roles – washerwoman, entertainer, lady of leisure, etc. – mainly painted by men. Laura Mulvey’s influential 1973 essay regarding the oppressive male gaze censored even female painters of the female form. But as neo-expressionism from ex-fascist countries helped revitalize a non-servile figure, painters like Yuskavage, Jenny Saville, Julie Heffernan, Anne Harris, and Hillary Harkness combined abjectness or female fantasy with unapologetic representational skill.

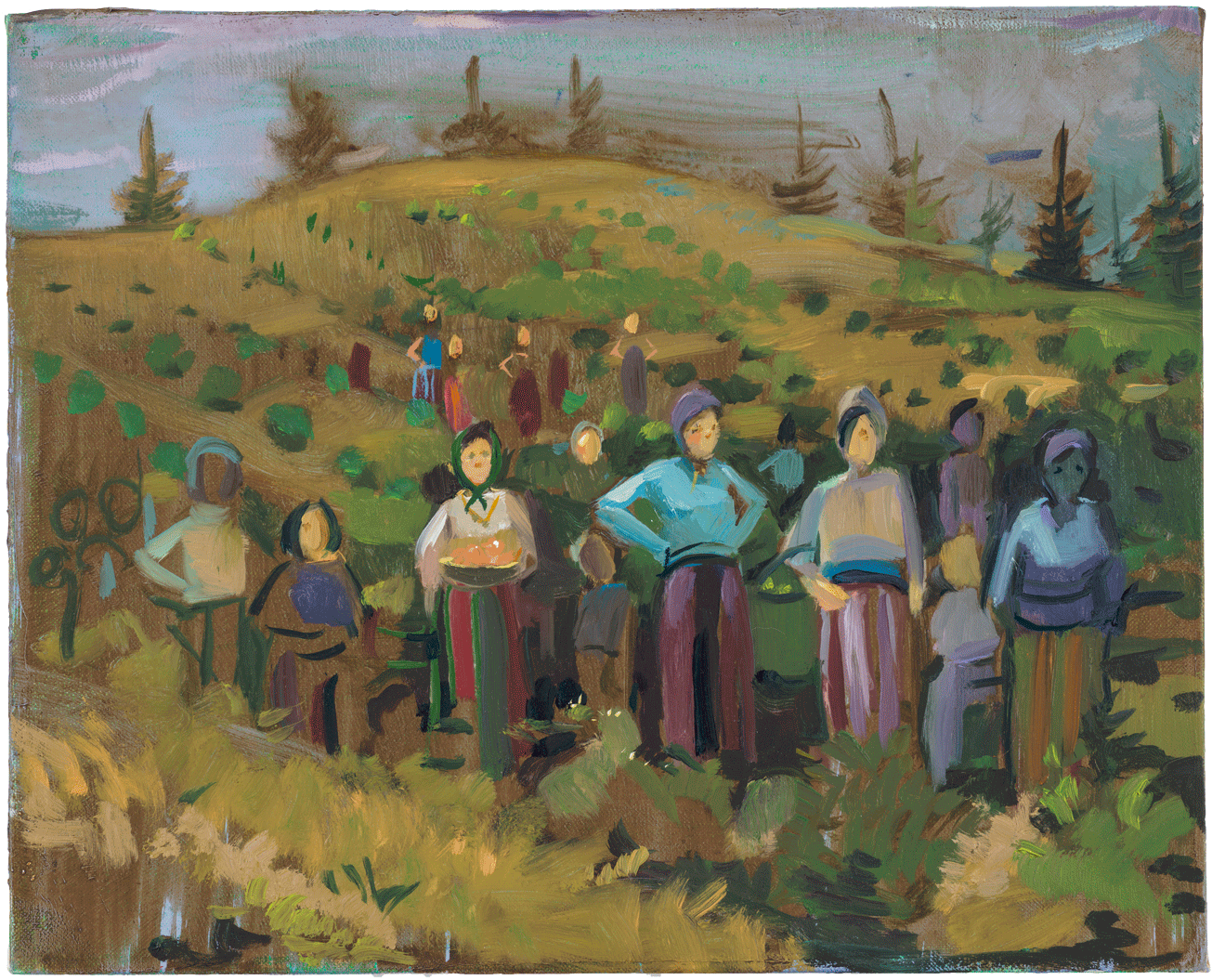

Women depicting strong women navigating reality in a man’s world, however, despite the examples of Alice Neel, Tamara Lempicka, or Kathe Kollwitz, largely went east during the Cold War. In “Peasants” and elsewhere, rows of babushka-ed women emerge from the landscape like nagging reminders; Yuskavage’s indulgent girls show no interest in meaningful activity, let alone work. Despite Cosmo savvy, they partake in the timeless congeniality recommended for females – drinking tea, offering wine or food, gathering flowers or gardening, looking hot. Girlpower poses shrink to the shallow comity and eroticism of fashion spreads.

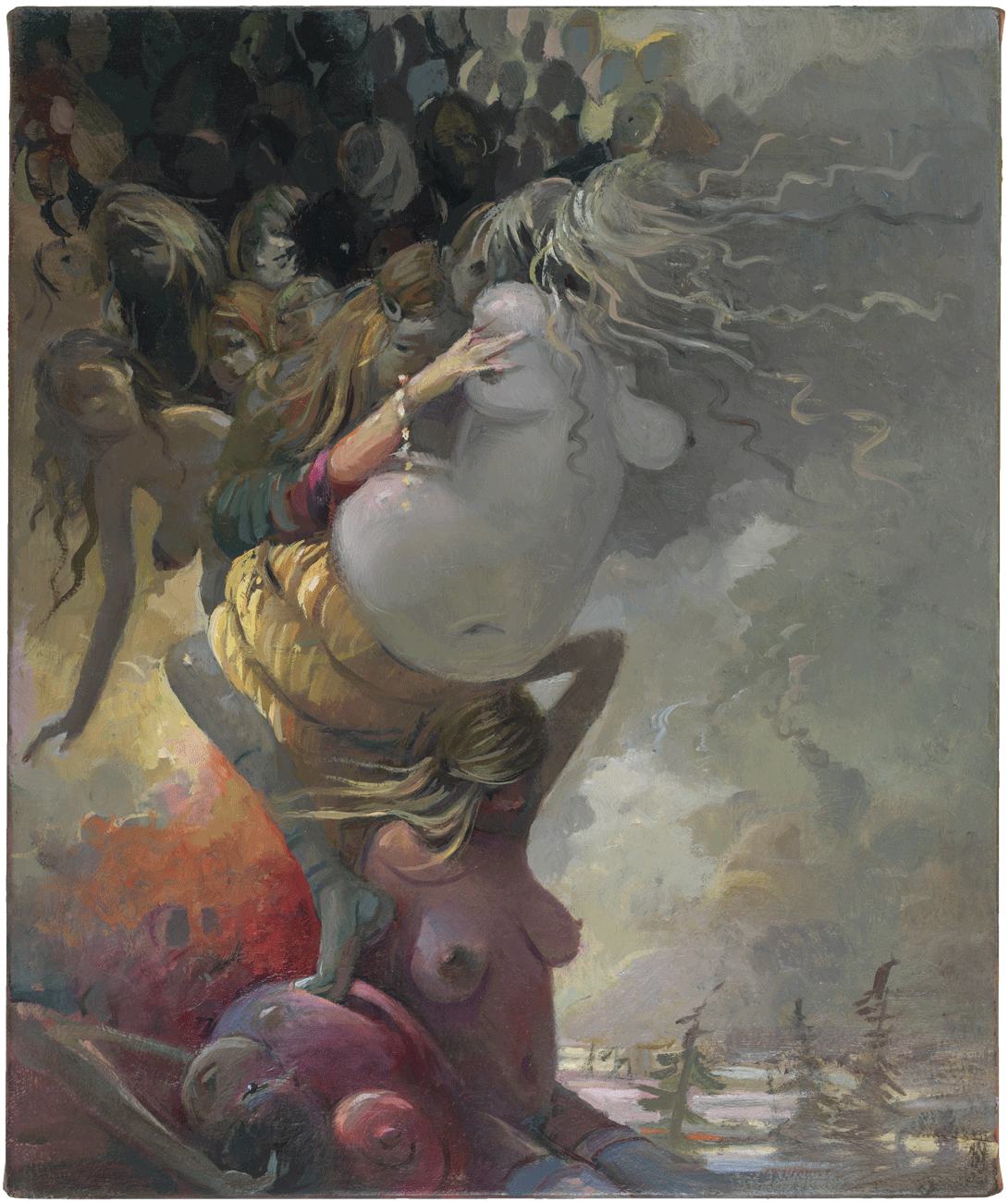

In the more recent “Pile Up” they aspire to heroism, a heavenward assumption into at least notoriety, the composition’s spiraling baroque complexity and symphonic tonality secured with cogent maneuvers of the brush. Seen en masse, Yuskavage’s addled girls slowly prod through passive-aggression toward far-off redemption.