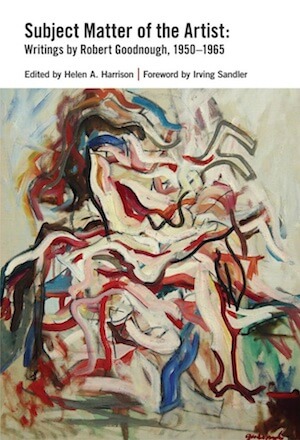

Subject Matter of the Artist: Robert Goodnough, 1950-1965

Edited with an Introduction by Helen A. Harrison

Foreward by Irving Sandler

Soberscove Press

Subject Matter of the Artist: Robert Goodnough, 1950-1965, a new book published by Soberscove Press, is a time capsule of sorts. It unearths a lost primary source, penned by a significant artist, one that sheds first-person light on some of the most iconic artists of the New York School. It also conveys, through the enthusiasm of its author, a palpable sense of the excitement of a painter consciously aware he is in the midst of a significant avant garde moment.

Irving Sandler, in the foreward, describes the ethos of this moment (1949-1950) and its influence on Goodnough. It was a “lively avant-garde ferment,” Sandler writes, “in which [Goodnough] was introduced to the latest and most vital art and ideas, and all the fresh options in contemporary art.” (p.9)

As a graduate student and protege of Tony Smith at NYU, Goodnough embraced these ideas. He sought out avant garde painters, not only making the acquaintance of key artists of the New York School, but also visiting their studios and interviewing them for a research paper. This important, nearly unknown piece of writing, titled Subject Matter of the Artist: An Analysis of Contemporary Subject Matter in Painting as Derived from Interviews with those Artists Referred to as the Intrasubjectivists, is the centerpiece of this new collection.

Goodnough is known primarily as a second generation Abstract Expressionist, the generation that included Joan Mitchell, Grace Hartigan, Sam Francis, and Norman Bluhm among others. He also penned the seminal ArtNews article, “Pollock Paints a Picture,” a first hand account of Jackson Pollock’s novel drip painting technique (also included in this new volume – along with an interesting new revelation about that text).

Pollock, we learn, was not the only important painter observed and interviewed by Goodnough. In Subject Matter of the Artist, he turns interviews with key icons of the New York School, including William Baziotes, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman, Adolph Gottlieb, and Willem de Kooning, into succinct, individual prose portraits. Historical and technical anecdotes from these portraits flesh out our understanding of these artists at the very moment they are making their mark on the history of painting.

In one interview, Rothko admits an initial aversion to visual art and discusses his relatively new effort to “eliminate any distracting awareness of paint by applying his colors without texture.” (p.47) In another, Goodnough offers a summary of Newman’s observation that “the act of painting and the bringing into existence of an art object are one and the same process. In music, a diagram is first created, then it is played on an instrument. The painter plays his instrument while he is creating it.” (p.53)

The interviews reveal shared ideas among these artists, yet opposing views also emerge, supporting the notion that the New York School was not as much a shared vision of a school of like-minded artists as an ethos arrived at through a variety of artistic motivations. Gottlieb, for instance, tells Goodnough that painting is “not only a matter of colors and shapes on canvas, but images made visible and integrated” (p.58) while Baziotes gives a contradictory statement, remarking that “reference to existing objects is not particularly helpful in contemporary painting.” (p.44)

It is this issue of subject matter, “an understanding of what is involved in approaching painting with no reference to existing objects” (p.42) that is Goodnough’s focus. His thesis resurrects for a 21st century audience the term “intrasubjectivism,” introduced in 1949 by José Ortega y Gasset to describe a non-objective painting approach. (p.42)

This approach, editor Helen A. Harrison explains, “lies at the core of what was then being defined as the new American painting, although many artists would replace ideas with even more subjective stimuli such as experiences and emotions. The artist was liberated from representation, but also unmoored from it.” (p.17)

It is clear the intrasubjectivism Goodnough explored as a writer informed his painting as well. Though he painted more and less overt subject matter throughout his career, he always seemed to privilege an improvisatory approach. As Goodnough recalls in a 1958 statement that concludes the current volume:

“the domination of the object to be looked at, always saying that a certain line should go in this direction or that, a red had to be here and a blue there because that was the way it was on the model, began to be limiting…” (p.75) Goodnough never accepted limits in his painting, embracing in his own work what he describes as the “feeling in the best work of American painters of the ‘wild’ which has been the heritage of this country.” (p.76)

Goodnough’s writing, newly presented in this book, allows the reader to feel the the excitement of being part of a small group of New York artists discovering and exploring entirely new territory in painting. To read his account is to be there the moment (characterized by Harrison) that American “wildness” succeeded French “finish,” as New York replaced Paris as the center of the art world.

Subject Matter of the Artist: Robert Goodnough, 1950-1965, Edited with an Introduction by Helen A. Harrison, Foreward by Irving Sandler, will be available from Soberscove Press May 15, 2013.

SHIFTER and Soberscove Press will hold a joint book launch, celebrated through a series of short artist presentations entitled Proposals for an Impractical Education. Speakers include: Corin Hewitt, Riley Duncan, Valerio Rocco Orlando, Adelita Husni Bey, Abdullah Awad, Tyler Coburn, Jesal Kapadia, Brian McCarthy, Malene Dam, A.K. Burns and Steven Lam.

The event will take place May 11, 2013 from 5-7pm at Parsons, 25 East 13th Street, 5th Floor (NYC).