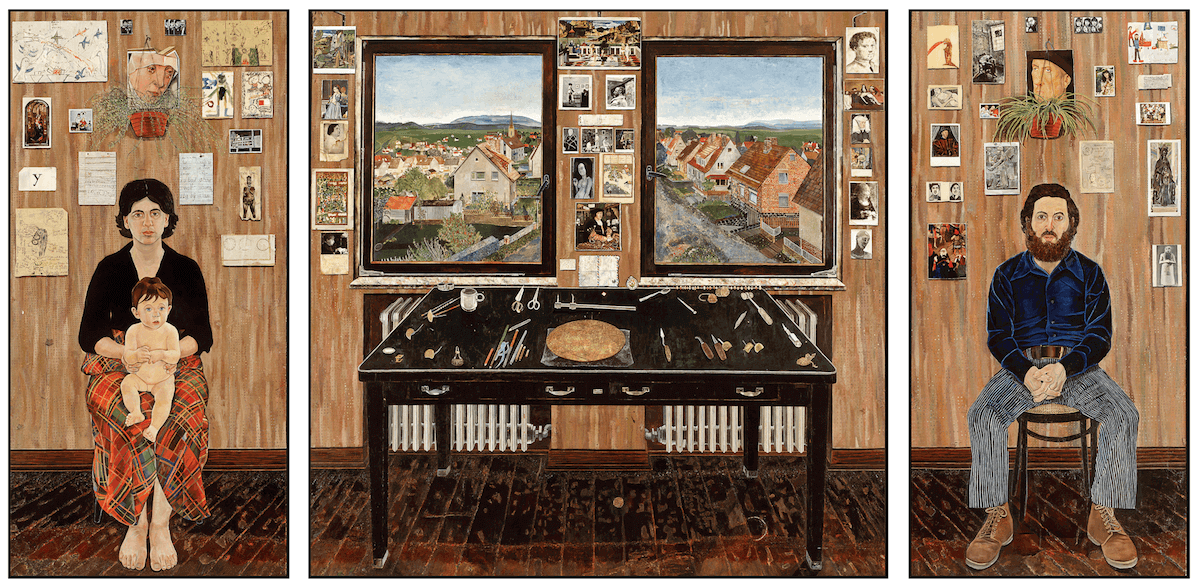

This is an edited transcript of a talk I presented at the occasion of the Perspectives on The Lasting World Symposium on Saturday, September 23, 2017. The symposium explored the work of Simon Dinnerstein in an exhibit, titled The Lasting World: Simon Dinnerstein and The Fulbright Triptych. This exhibition at the Museum of Art and Archaeology in Columbia, Missouri, runs through December 22, 2017 and then travels to the Arnot Art Museum, Elmira, New York (March 9 – June 30, 2018) and the Nevada Museum of Art, Reno, Nevada (July 21, 2018 – January 7, 2019).

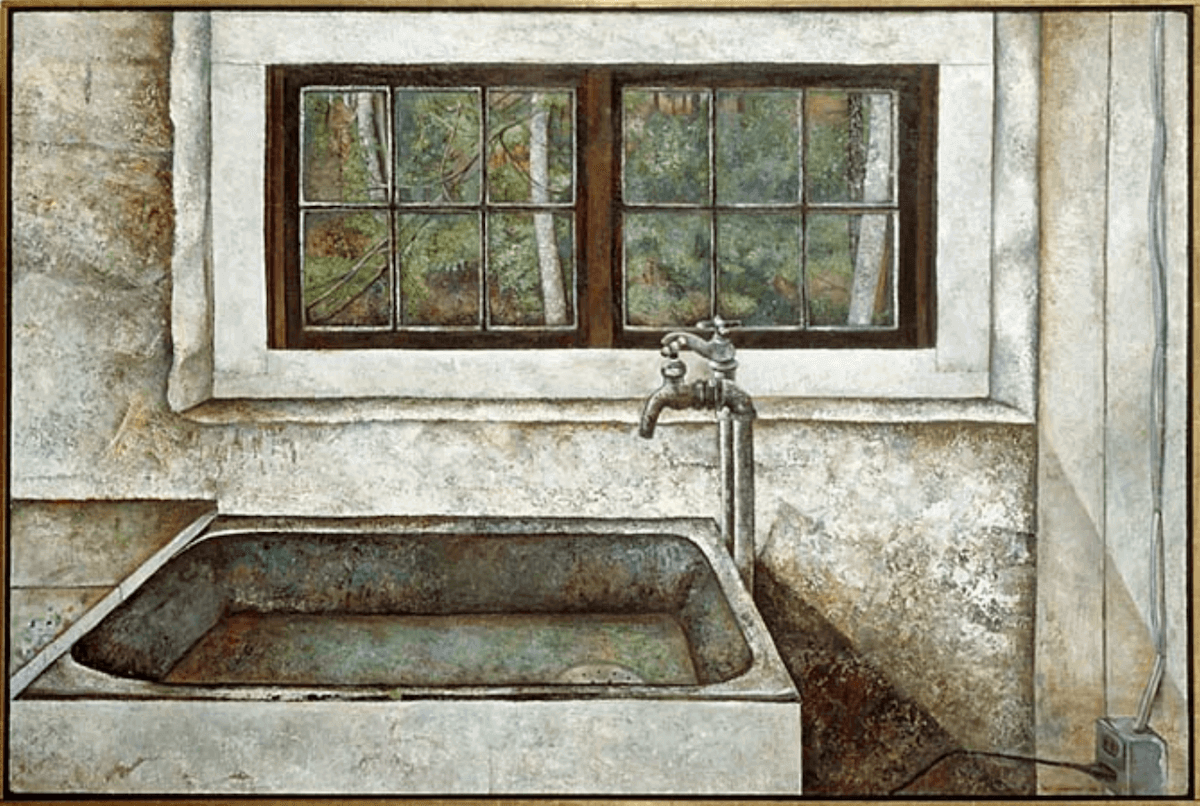

In this brief exploration I am going to try to turn our collective attention to sinks and windows, to see if we can think along with two great artists who have found remarkable ways to span the strange distances between spaces, centuries, and experiences. Simon Dinnerstein and Antonio López García have built their careers on tenacious attention. People, places, objects – as well as their overlapping associations and meanings – have come alive under the gaze of these two artists. In a time when our attention is called away incessantly, the works of Dinnerstein and García stand as exemplars of the great value our focused minds may create.

There is far too much material between these two artists – and the constellation of artists who surround them or who have been influenced by them – to give the topic of attention within their work its full due. Instead, I want to look at a cross section of just a few works that demonstrate the evocative affinities these two artists share. Let us consider sinks and windows.

The Sink: a place where artifacts of our consumption are purged. It is a site where we return certain tools to an original state, a zone of physical renewal or reconstitution. Where cleanliness reigns. The Window: a place where we see and dream. Where we find a stable site from which to take in the rushing spaces beyond. Through windows we can experience the daydream reverie or the notational fact – sometimes simultaneously. We look out to see if the mail has come and – sometimes, like happened to me recently – are instantly reminded of childhood. These are liminal zones. They are thresholds, membranes. Transitions happen across these surfaces, just as they do in paintings. Good artworks never resolve into just windows or doors. They always present a different kind of oculus: a relational conduit through which we may move.

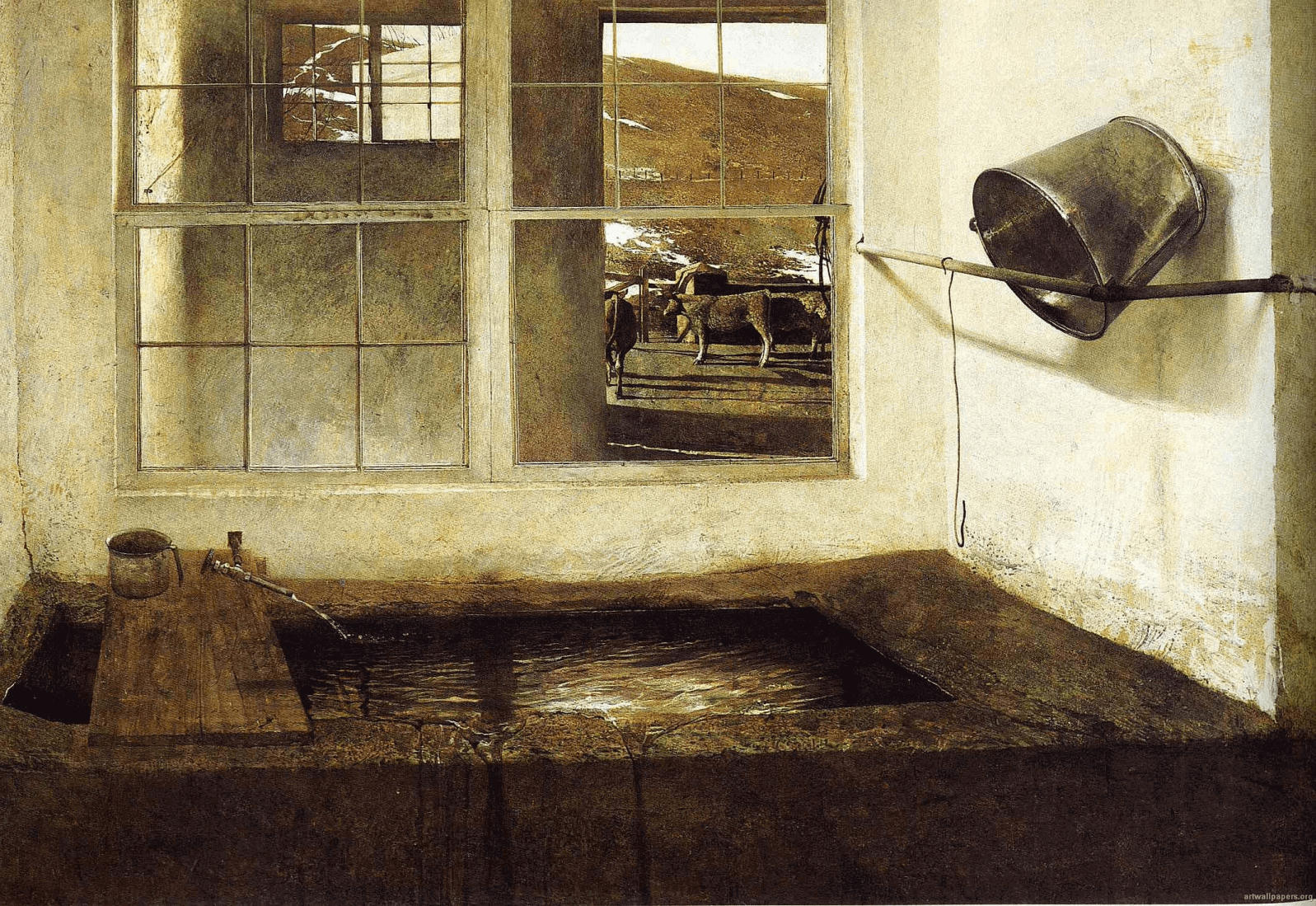

Critic Robert Storr famously dismissed Andrew Wyeth’s work ahead of his massive retrospective in 2005 1 and again after the artist’s death in 2009 2. The charges that Wyeth’s works were “anti-modern” or “illustration” 3 could, and have, been leveled at both Dinnerstein and García. Of course, there is nothing wrong with illustration as such, but these artists are doing something quite different. They are evoking the poetry of experience. Illustration amounts to a one-to-one relationship between the image and the narrative it tells (or, as the case may be, the product it sells). Artworks such as ones created by Dinnerstein and Wyeth are not illustration because they do not tell us any one thing. Rather, they remind us of beingness. They manifest the mysteries of the human condition. Thus the plain, everyday objects among which we make our lives must feature in their work.

As to the “anti-modern” accusation, we must assume that what is really meant by this wording is that these artists resist the pressure to be overtly political. But does this mean their work is definitely not political? Far from it. To depict an orderly, hopeful tableau dedicated to family and history, as Dinnerstein did in his Fulbright Triptych, was certainly political. To create it in Germany, where the wounds of war were ever-present, was political. To create it in a time when the carnage of Vietnam was blatant was political. Family is political. Parenthood is political. Deep looking is political. I would argue that the Fulbright Triptych resounds with Dinnerstein’s recognition not merely of his own time, but of the deep historical time of human engagement. It is a visual salve and balm, every bit as necessary and symbolic as were other, more directly political artworks in the 60’s and 70’s.

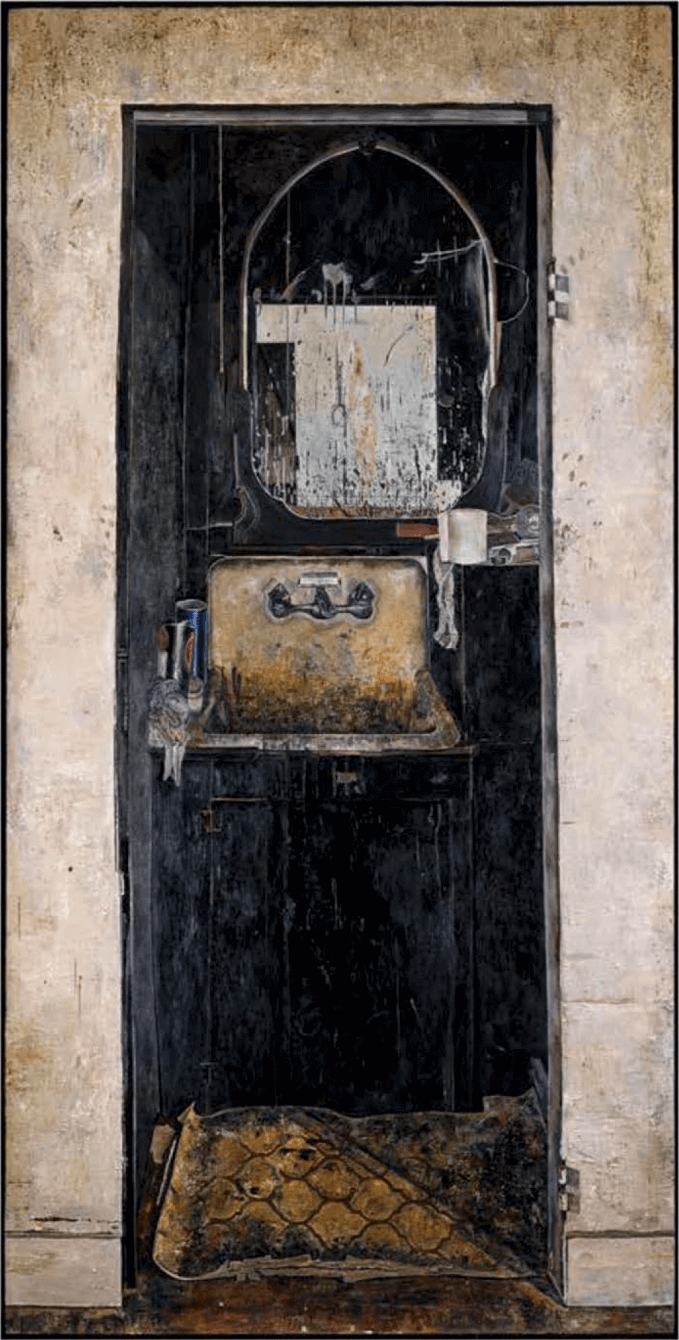

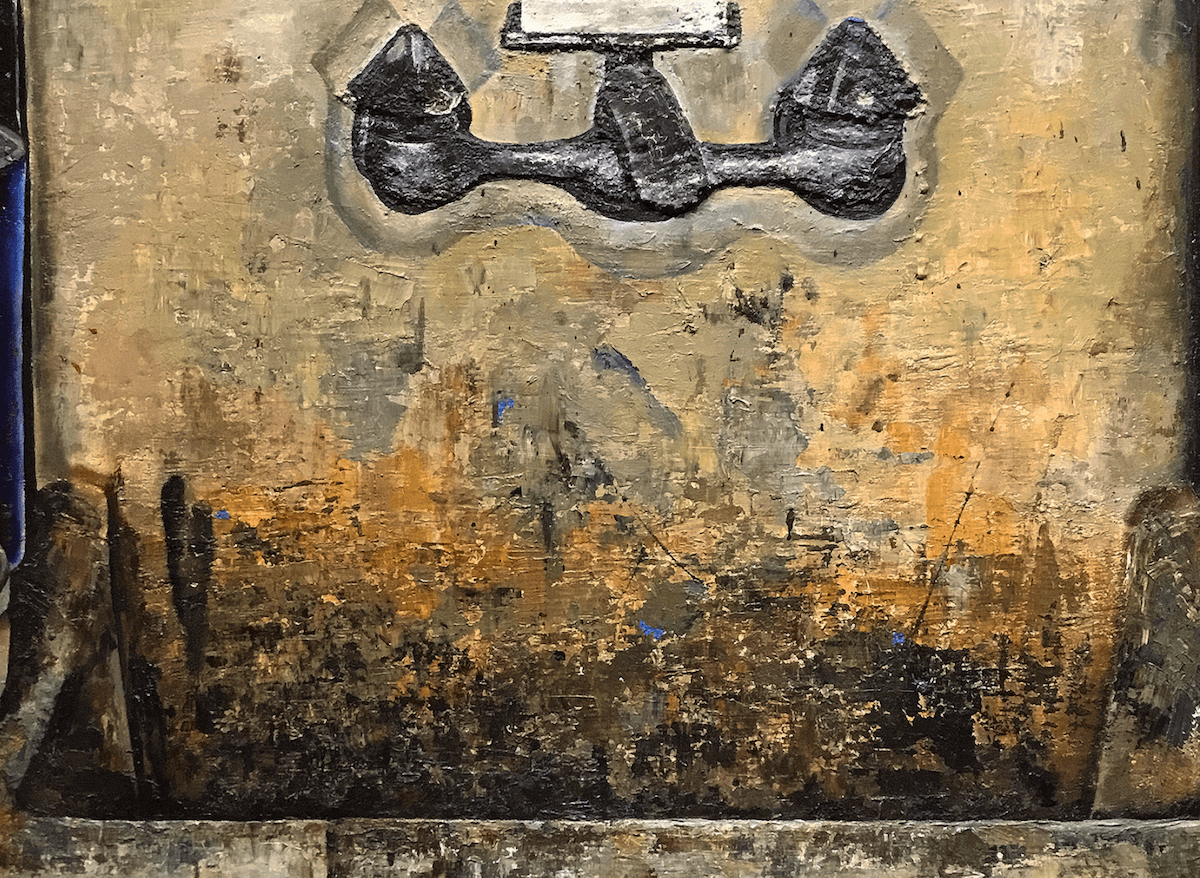

In the eyes of Dinnerstein, García, and Wyeth, darkened windows and dirty sinks become embodiments of profound understanding. What is happening in the artist’s mind as they pay attention and ask us to pay attention? How do banal, everyday objects and spaces take on trans-mundane importance?

We see the build up of certain types of marks – some in service of the illusion, some in service of the design. In a sense the aim here is to be more real than real. How? By going beyond the depiction of the plasticity of the form and suggesting to us what our hand would feel if we were to touch it. That haptic aspect is huge in Dinnerstein’s work. There is an experiential shift happening. It is not merely about passively receiving. The mirror neurons in our brains fire in recognition. The artist’s incisive and insightful observation translates something more than what is seen. We get the feeling of seeing beyond simple description. It is the sensation of living over time. Pushing beyond the facts of the object or space, the artist is leading us to a core reality beyond those things. The act of looking at what is there allows us to see more than what is there.

Is it oxymoronic to suggest that pragmatic gaze can function as an entrance to poetical understanding? No, because it is use that leads us to the resonance of meaning that accrues over time. It is not contradictory to suggest that distilled attention in the service of translating a four-dimensional experience into a two dimensional format results in poetry. Dinnerstein used those tools he depicted in The Fulbright Triptych. García used that famous bathroom sink – for decades. And we use their paintings – much as an adept might use a mandala or other contemplative form – to focus our own minds. Like all great wisdom, artworks crafted from acts of observation and translation cause the banalities that surround us to blaze with transformative power. Through attention they transcend the facts and move toward an associative, constructive truth.

Attention is an act of radical presence. We live in an era – one that started around 2004 with the advent of Facebook – where increasingly people find themselves physically dislocated from their social experiences. The Pew Research Center began tracking social media usage in 2005 and at that time they estimated that 7% of adults in the US used social media. Currently the estimate is nearly 70% 4 and growing. There has been a cosmic shift in how we attend to our surroundings, the manner in which we engage with them, and the quality of the experiences we have in them. Certainly this is not all bad, but it ought to give us pause.

“Art making is, at its core, about paying attention. Likewise, good viewing of artworks – regardless of their form – requires contemplation of that to which artists have paid attention. The modern proliferation of images and information and the layers of technology between our knowledge and our physical experiences can be avenues through which we may choose intense, attention-demanding engagement” 5but all too often they are not. We say, “paying attention” for a reason. Real focus costs us something, whether the situation is spending time with loved ones, students, or artworks. It costs us time, intention, and presence, yet it rewards us with genuine experiences.

That is why works such as Dinnerstein’s are so important. They challenge us. They posit a connection between representational attention and symbolic – yet very real – intent. That is, they suggest that the gaze of an individual can catalyze into transcendent, meaningful vision, crafting an image that is more than the sum of its parts. It can be more iconographic and designed – such as Giotto, van Eyck, or Pontormo – or it can be more perceptual – like Giorgione, Ribera, or Freud. I see Dinnerstein and García bridging the distance between these two groups. García defaults to observation, Dinnerstein to design, yet both operate with powerful meaning-making attention. Whether to observe or design, the strenuousness underlying the work is palpable.

To what end, we might ask? Why all of this obvious effort?

Painter and educator Roberto Rosenman, in his wonderful essay about Antonio López García, talks about the necessary fiction inherent in representational art. It’s a fiction done in order to “make the unstable world stable.” 6 García and Dinnerstein have both engaged in this stabilizing action through their attention, but they also undertake what Werner Herzog calls “the ecstatic truth.” 7 That is, they go beyond simple reportage, beyond documentation, and present a fiction that is, in a sense, truer than true.

That realization is what I hope viewers take away from seeing this work. The sink is more than a sink. The window is more than a window. The attention of the artist evokes the attention of the viewer, and their shared attention results in a powerful, resonant poetry of experience.

The exhibition catalogue for The Lasting World: Simon Dinnerstein and The Fulbright Triptych, featuring essays by Rudolf Arnheim, Alex Barker, Tom Healy, and an interview with Lynn F. Jacobs on the Triptych form is available through Alibris and simondinnerstein.com

Notes

1 Deidre Stein Greben. Wyeth’s World. ARTnews. October 1, 2005. Available online: http://www.artnews.com/2005/10/01/wyeths-world/

2 Larry Rohter. For Wyeth, Both Praise and Doubt. The New York Times. January 17, 2009. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/17/arts/design/17deba.html

3 Timothy Cahill. A new window on Wyeth. The Christian Science Monitor. November 10, 2005. Available online: https://www.csmonitor.com/2005/1110/p11s02-alar.html

4 Pew Research Center data sheet, January 12, 2017. Available online: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/

5 Mathew Ballou. The Art of Mediated Attention. Neoteric Art, January 16, 2015. Available online: http://neotericart.com/2015/01/16/the-art-of-mediatedattention-by-matthew-ballou/

6 Roberto Rosenman. Beyond Realism: The Drawings and Paintings of Antonio López García. Available online: https://www.robertorosenman.com/antonio-lopez-garcia/

7 Daniel Zalewski. The Ecstatic Truth: Werner Herzog’s quest. The New Yorker, April 24, 2006. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2006/04/24/the-ecstatic-truth