Susan Lichtman: In My House

Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects, New York

June 14- July 15, 2017

Susan Lichtman’s paintings situate roughly midway along the stylistic spectrum from representation to abstraction continuously mined since the 19th century, despite Cold War polarities, and bring a novel female perspective to Intimist iconography. With Fairfield Porter and David Park she shares formal emphasis, a sense of light informed by Impressionism, and a descriptive shorthand that echoes primitive appropriations by Picasso and Matisse. But Lichtman’s work shows a denser cubist fragmentation of experience that explores personal subject with judicious reservation.

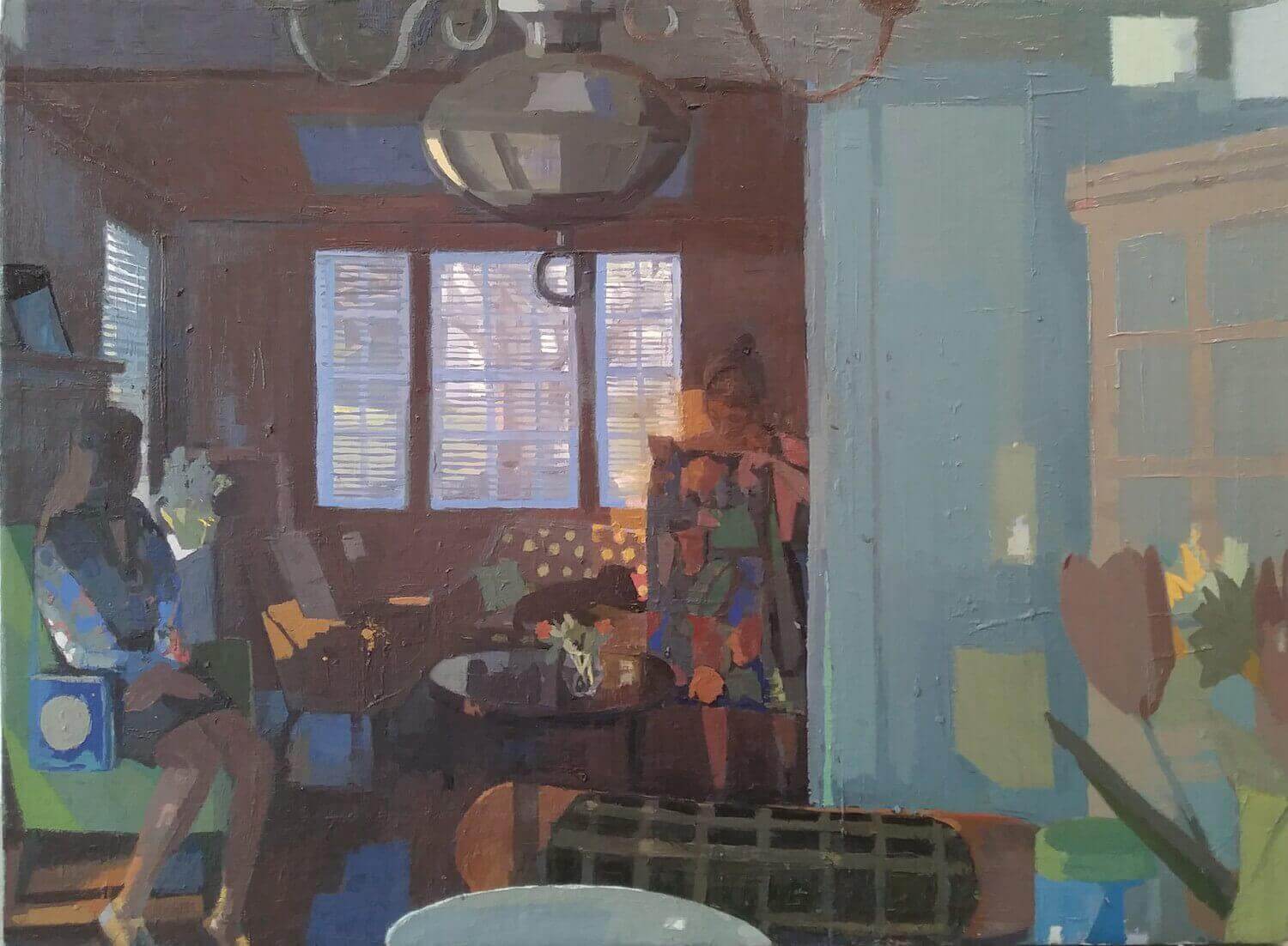

In Floral Jacket, one girl waits for another’s decision regarding a clothing option in the dim, red recess of a room framed by green-blue shapes. They are as engrossed in their considerations as they are absorbed into the lush abstract pattern on the picture plane. Slowly, the foreground – hanging light, flowers, and bowl – pans out, implying the table and the observer seated there, regarding them.

More is known about Cubism’s empowering of formal language toward unfettered abstraction than about its impact on perception, such as the divergent tenors of disquiet Giacometti and Dickinson reached. Lichtman’s uncertainty, set in proximal, peopled spaces, soothingly lit, is comfortable. As a motif, the interior’s shallow but dynamic space limits variables to expected objects; darkness is mysterious yet knowable and easily tempered by artificial light. When the interior is a home (as with Las Meninas), comportment as defined by human function is predictable. 1 Narratives meaningful to the painter but opaque to the viewer, invite speculation.

In Equinox Meal, wider than its more colorful gouache study, the seated group (one of whom looks at the observer) doesn’t interact with a woman strolling past who glances their way. Somehow not out of place, perhaps prefiguring those unaware of her, she seems at ease in her business attire and casual posture, reminding the viewer of the roles women play and model in both keeping and funding a hearth and how they present themselves to the outside world. Descriptive development of the table area renders things less like types: how a fork is held, the transparency of a Brita pitcher, are careful moments of private optical truth that play delicately off bold abstract shape and texture.

This dream-like woman has a stronger role in the study for Equinox, where her contrasting contour balances the pointed yellow table at the opposing edge. Lichtman’s paintings express construction in action – the behind-the-scenes visions Cézanne imparted to Cubism, which AbEx would place center stage. This open compositional process, in Lichtman’s case also perceptual, responds to conditions as encountered. Lichtman explains, “It’s as if I was zooming out from a close-up of a particular form, slowly revealing what might be in the periphery… I can only do this with places I know very well, where I know how light falls and how figures interact with things… I don’t start with that positioning of shapes; I discover them.” 2

When the hierarchy of genres established by the French Academy was overthrown by the avant-garde, Baudelaire encouraged the depiction of “the passing moment and all the suggestions of eternity that it contains,” and painting focused on hobbyhorses – Degas’s dancers, Toulouse-Lautrec’s demimonde, Morandi’s bottles, etc. 3 As photography sidled onto painting’s turf, painting increasingly valued invention over imitation. Each prospect of Mont Sainte-Victoire by Cézanne represented a unique compositional experience and innovation.

Because Lichtman’s preoccupying motif is also actually familiar, looking provokes memories stored in passing – not only of the daily rituals of life measured out in coffee spoons, but former versions and actions of the home’s occupants – that might also populate her pictures. (Palaces were no doubt employed in mneumonics because associating memories with familiar interiors happens easily.) 4 Aside from males in their libraries or studios, Intimist interiors, mostly by men, show women in erotic or domestic roles – as unavoidably Other. In contrast Lichtman descriptions are first person, merging the mother/artist’s surveying eye. Her interiors favor the middleground from a position just out of earshot but easily monitored, the unconscious awareness parents scan across their visual fields.

Rosa Moves Out conjures the architectonic, textural and tonal aplomb of Motherwell and late Braque atelier paintings. Beyond surface drama we see familiar poses, gestures, attitudes or activities, the near figure presumably a daughter assuming her mother’s summary gaze before leaving.

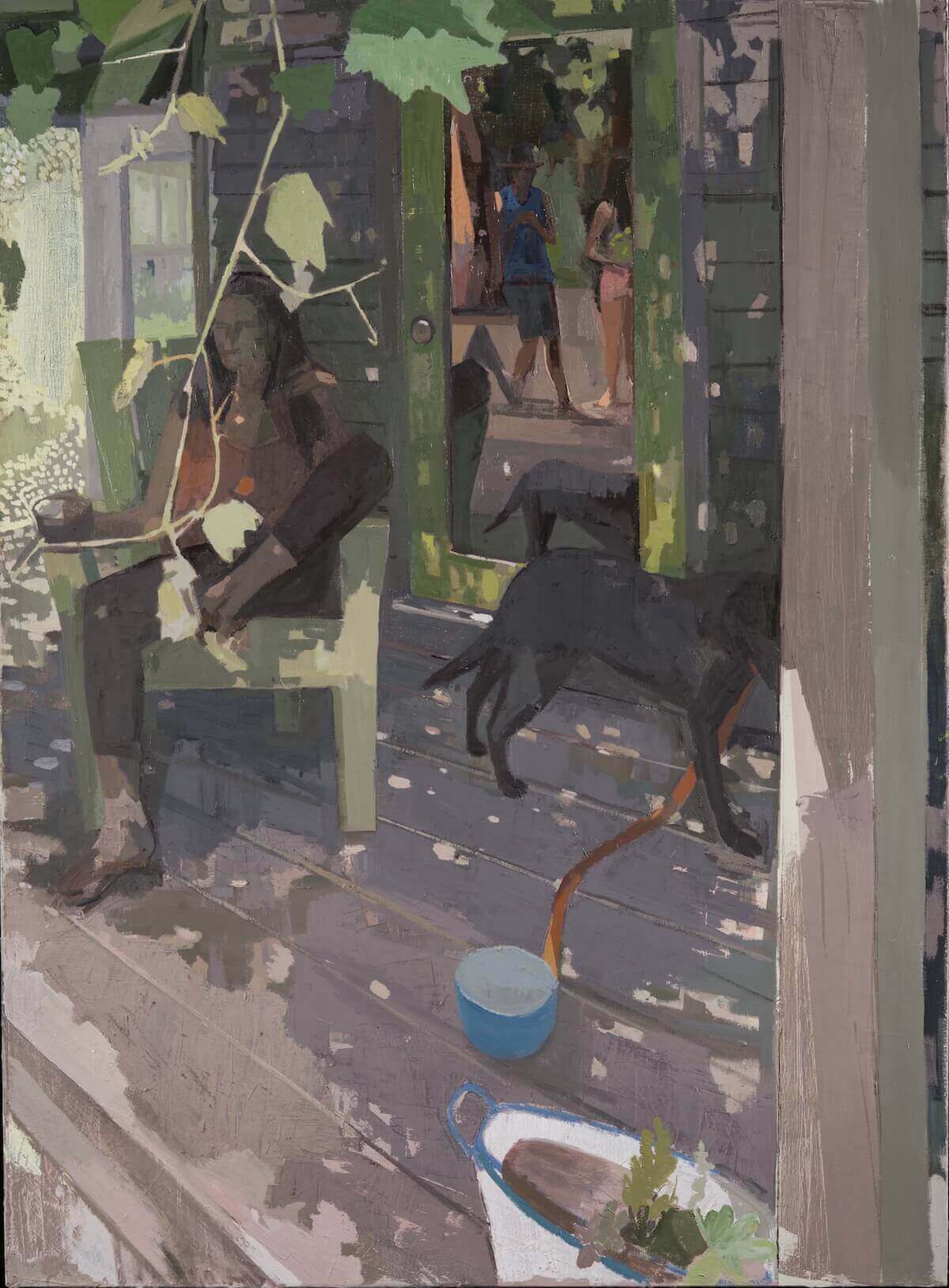

If “every age has its own gait, glance and gesture,” painting can thank photography for collecting micro-poses for later examination. 5 Lichtman seamlessly folds this information into her perceptual process; Under Grapes and Coffee Outside apparently utilize the same shot of a girl in a chair though their tonal ranges, station points, and reflections differ. The complexity, scale, and perspective here is reminiscent of Vuillard’s late portraits in interiors while the accentuated, closer leaves left as negative shapes and spots of light even invoke Clyfford Still’s searching marks.

Dappled patches hold differing spatial locations and also flatten. It’s hard not to be reminded of Monet’s shifts between his pond’s surface, its depths, its reflections, and when he lost the horizon and bent the water nearly perpendicular, up to the picture plane. These effects are especially captivating in Coffee Outside. Its Balthus-like palette quiets the scene, which includes an enigmatic foregrounded girl who seems friendly, yet remote as a caryatid. Lichtman achieves her goal of avoiding sentimentality, but happiness still comes through. 6

Notes

1 https://paintersonpaintings.com/margaret-mccann-on-diego-velasquez

2 http://paintingperceptions.com/interview-with-susan-lichtman/

3 Baudelaire, The Painter of Modern Life, 1863

4 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Method_of_loci

5 Baudelaire, The Painter of Modern Life 1863

6 “I have liked this sense of distance, especially when painting my own home and family, as a way to avoid sentimentality.” http://paintingperceptions.com/interview-with-susan-lichtman/