The following essay is the third in an occasional series featuring important but under-known writings by the painter Sargy Mann (1937- 2015). This series is made possible by the generosity of the Sargy Mann estate. Learn more at sargymannarchive.com

The exhibition Sargy Mann: Suffolk 1976 will be on view at Cobbold & Judd from Saturday 21st October – Saturday 4th November 2023.

In the catalogue, Peter Mann notes that “In the early 1980s Sargy wrote a series of essays for different publications on Bonnard, Cezanne and Dufy and these are perhaps the best way of understanding his own work from the late 1970s. Central to everything he wrote was a disagreement with the concept of ‘Realism’ as it was, and perhaps still is understood in art history. In essence it was becoming increasingly clear to him that the ‘reality’ he experienced in the world and also from the work of great painters was too rich and too personal to be described by some universally understood pictorial convention.” Sargy Mann’s essay on Dufy is presented below with a new introduction by Peter Mann.

Introduction.

Almost all of Sargy Mann’s writing on the work of other artists came initially from his desire to understand something about their paintings which might help him with his own work. He only wrote about painters he loved and who he felt were working in essentially the same mode as he was.

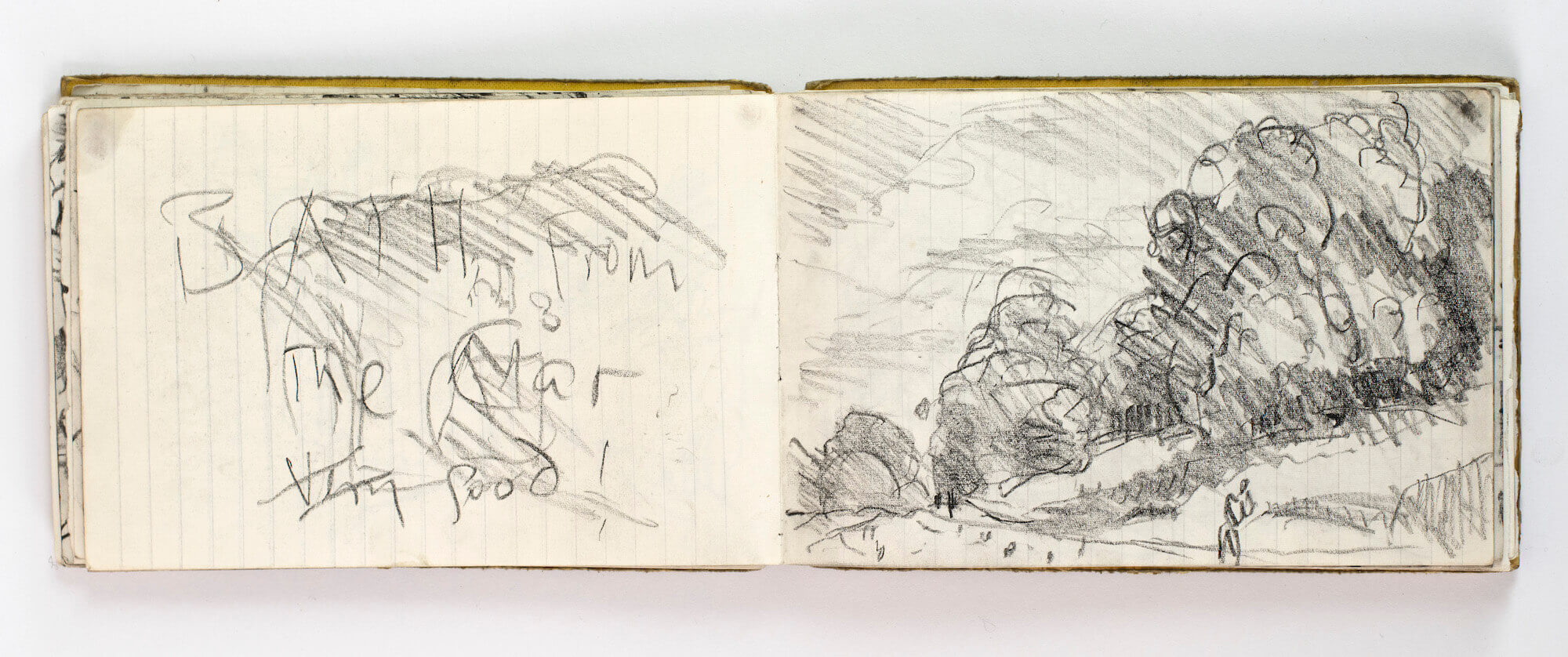

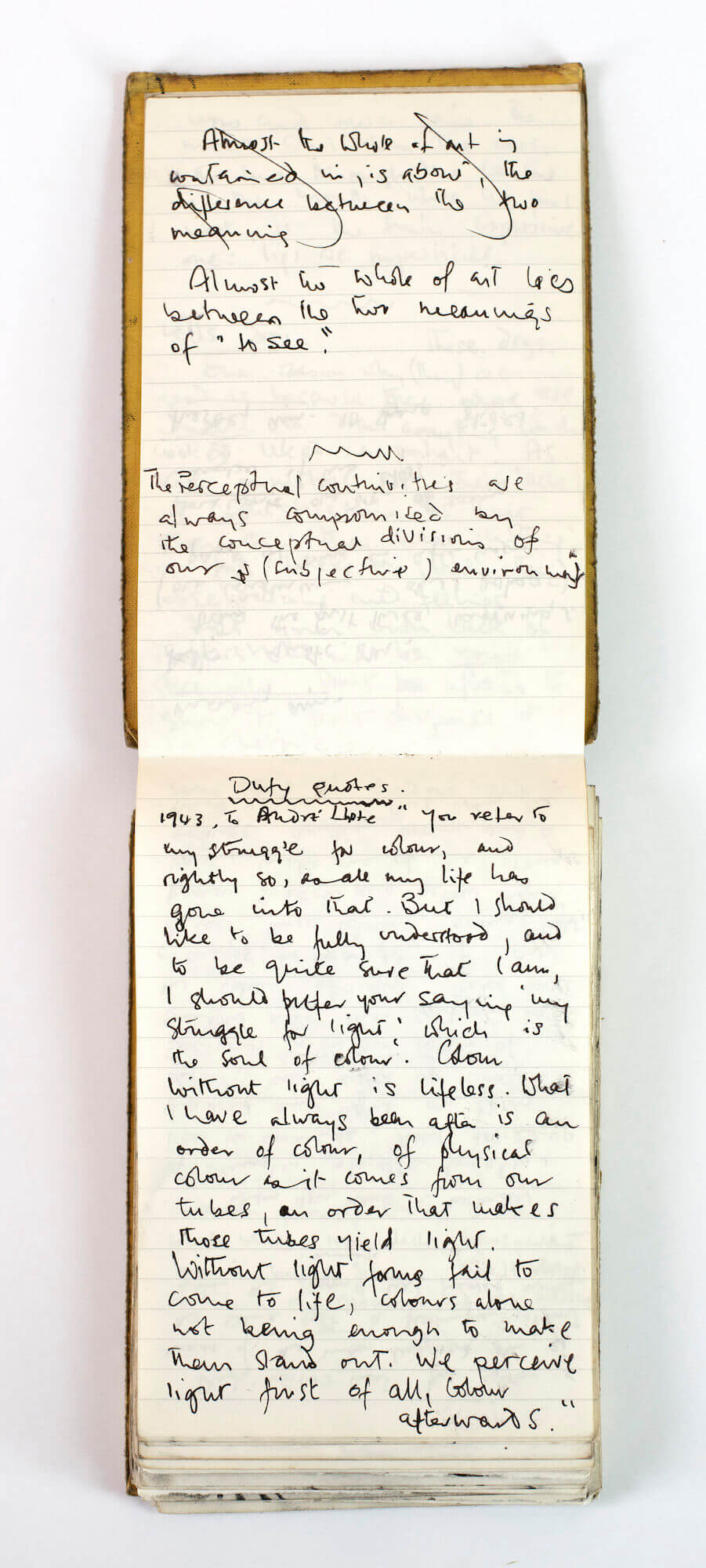

There is a central theme in his writing which is a disagreement with the way ‘realism’ was and perhaps still is understood by most art historians. He felt that the work of many great painters was misunderstood because influential people writing about them didn’t have a sufficient grasp of the more subtle aspects of perception. Which led to what Sargy felt were brilliant inventions being talked about only for their decorative qualities. These ideas ultimately came together in an easy called ‘Shared experience’ written in the 1990s but many of them appear in embryonic form in his sketchbooks from the 1970’s.

In the early to mid 1970s Sargy had been painting in a way that was totally driven by searching for patterns of colour that gave off sensations of light, “Drawing had taken very much a back seat” in his paintings and he regretted this fact. Writing about this period much later he said “The problem was, how could there be drawing and colour in the same painting?… When searching for a spatial experience the eye moves very fast, it is like flying. Your eye hits some grasses near your feet, skims the field, dipping and banking, climbs up the bushes, up and over the poplar and willows and off into the sky to circle and dive like Hopkins’s Windhover. These rushing, dizzying circuits explore and build to an ever greater experience of the whole articulated space in which one finds oneself. Lines can mirror these movements; a line can make that equivalent journey across the rectangle. But every point on that journey is giving off a different sensation of coloured light and requires a different colour at that place on the canvas. How can one do both?”

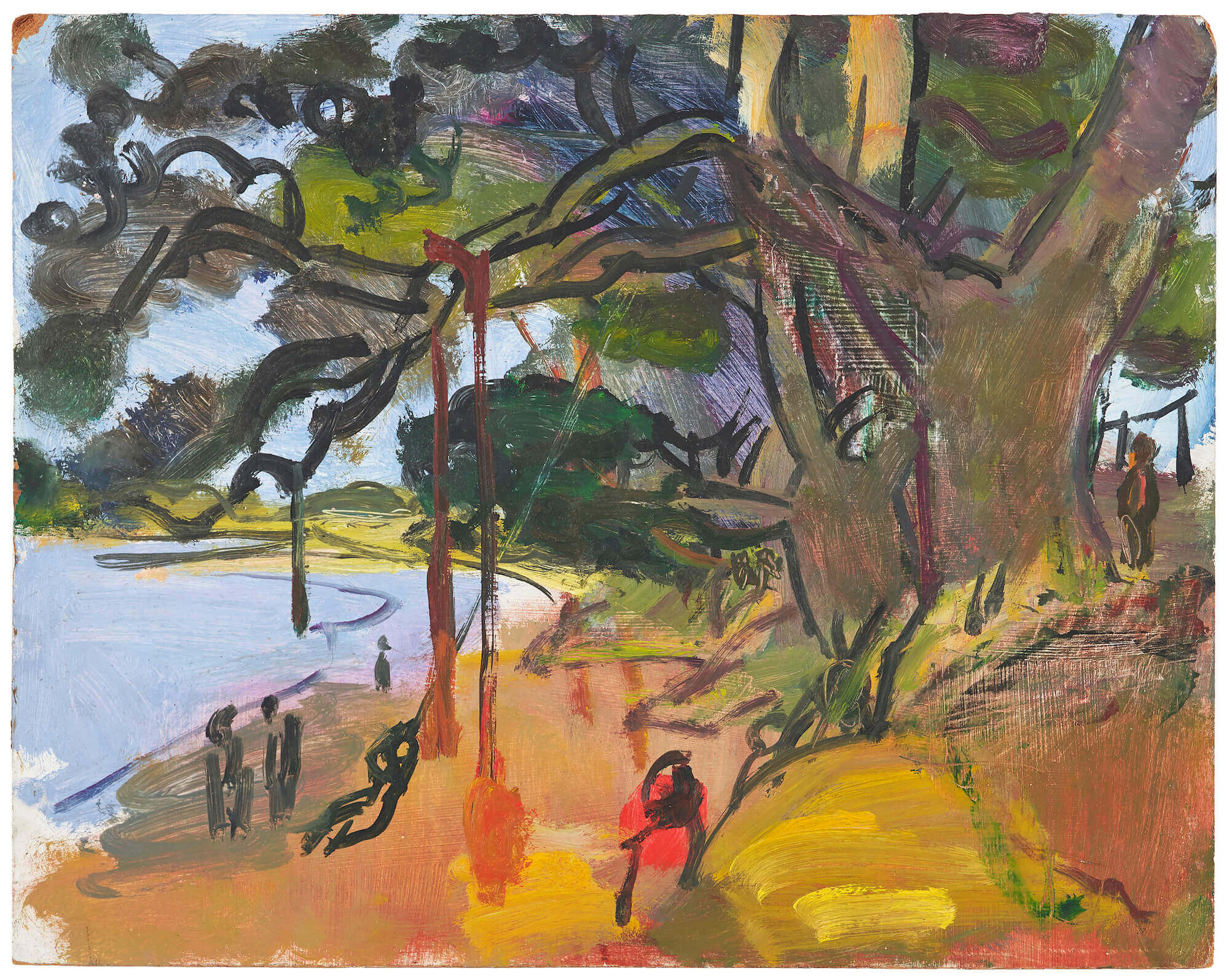

Thinking about the work of his favourite painters Sargy realised that Dufy was the most extreme example of the separation of line and colour and with much trepidation (as he had ‘a hatred a fear of any style-conscious way of painting’) he tried working in a way that was undoubtedly heavily influenced by Dufy, The Swings at Iken and Thorington Hall are two examples. This way of working lasted only perhaps a few weeks in the Summer of 1976 but Sargy always talked about these paintings as having been important to him and the Summer of 1976 in general as having been a very significant moment in the development of his work.

Raoul Dufy was an example of a painter Sargy felt deserved much more serious consideration than he was generally given. The essay by Sargy you are about to read was written in 1987 for the catalogue of a Dufy exhibition at JPL Fine Arts in London. On the surface it is an essay about Dufy and some of the works in that exhibition but it is also an attempt to define a particular mode of figurative painting which Sargy was engaged in himself and felt sure was what the masters he admired were also doing.

—Peter Mann

On Raoul Dufy

by Sargy Mann

Looking at “Village de Normandie”, we wake to a dazzling world of light and space, a bit cold for it has been raining. Bricks blaze in the low sun, and from the massive chimney stack of the near house we soar, via soaked slates and the clean geometry of spire and transepts, to the high sky, where wind scattered cloud remnants disperse. Far further the bank of rain cloud withdraws, its vast forms lit by the same low sun. We swing away to left down the village street, only to climb, roof behind roof, into the sky again. Or, to right, we drift far down to rest on the still river, or go deeper, into its reflections. Late on we discover the bank at our feet and we are fully convinced. This ravishing effortless decoration (“with the tip of a brush a curve or spiral can easily be made; it’s not an unpleasant sensation”) has become an intense experience of being somewhere – of being somebody: Dufy! Here is the gift of a great realist. “What I wish to show when I paint is the way I see things with my eyes and in my heart … ”

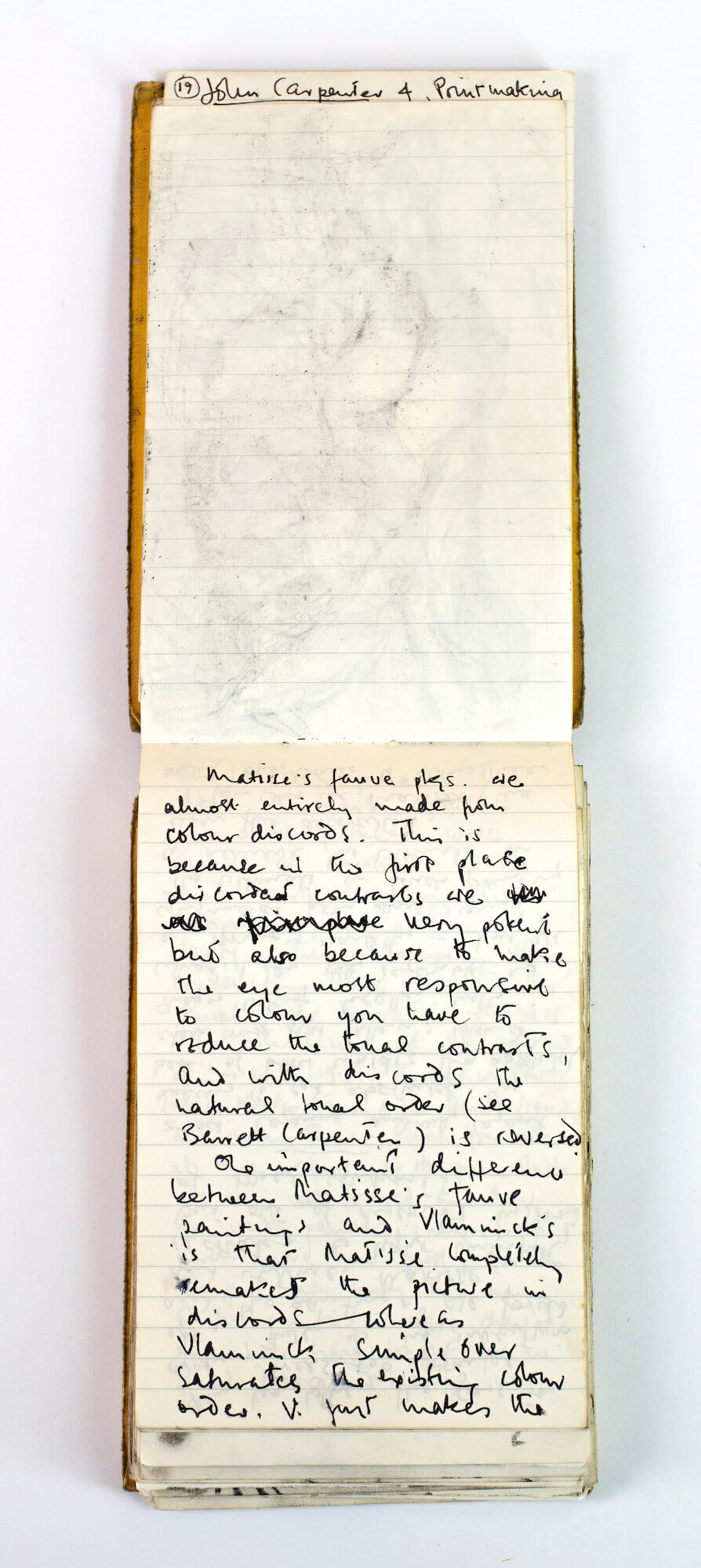

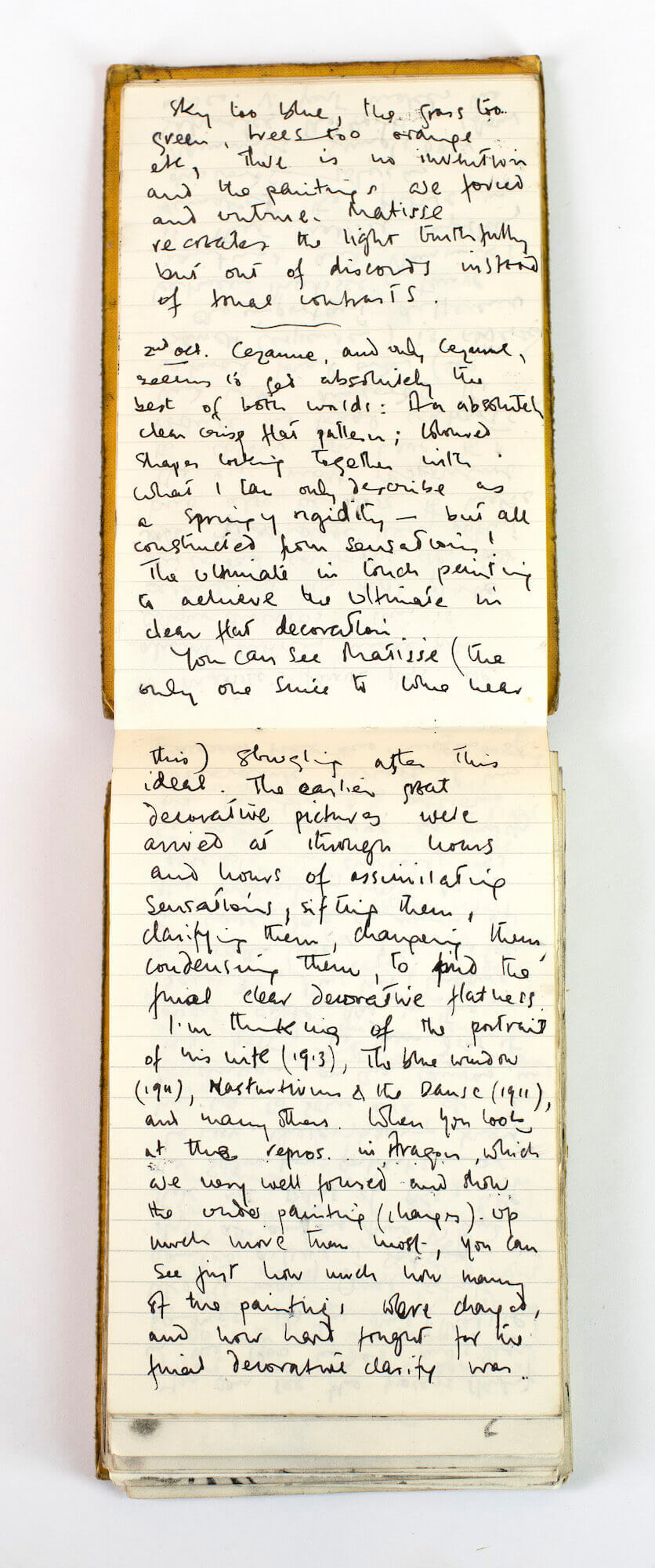

Dufy was a brilliant draughtsman and an inspired colourist. A mature Dufy is an astonishing balance of radiant colours across which is drawn a line of speed and precision and particularity. The pattern is so engaging, so decorative, and the references to reality so charming and witty, that too few go deeper or believe that depths are there. This is the fate of modern realists; of Bonnard and Matisse as well as Dufy.

The reason for this is the changing role of “appearance” painting. From Giotto onwards painters sought to understand and represent the appearance of the world; for its own sake, and to increase the dramatic possibilities of their compositions. When the Impressionists dispensed with literary subject matter and gave their undivided attention to their visual perception of nature. Monet finally got to the bottom of appearances. This and the fact that the camera was beginning to make its representation of appearance commonplace meant that appearance began to lose its interest and excitement for painters. Paintings had had to provide “common experience.” The viewer recognising the world he knew, was disposed to believe what was going on in it: a Baptism or a Bacchanal. Everyone recognised his own experience in paintings, some might find that this had been replaced by the true subject of the painting which is the artist’s experience. When, as with modern realism, the medium of expression is no longer essentially “appearance”, the viewer who fails to receive the artist’s experience tends to see, not his own, but the flat pattern of the painting itself. This leads the faint-hearted to say that such paintings are “merely decorative”, and the more seriously misguided to speak of “the affirmation of the picture surface at the expense of an illusion of reality.”

Dufy arrived at his mature style gradually and via many influences. He was very thoughtful and reasoning, as well as sensual and intuitive. While working as a clerk for a coffee importer in his home town of Le Havre, Dufy painted beautiful firmly made pictures with Corotesque tonality. “l revelled in the light peculiar to estuaries, comparable only to the light I later found in Syracuse; radiant until about the 20th August; from then on it grows more and more silvery.” At twenty three, in 1900, he got a scholarship to study full time at the Beaux Arts in Paris. He became influenced by Impressionism and his paintings got lighter and more obviously coloured. They also began to sell.

In 1906, as soon as he had seen Matisse’s paintings of the previous year, he began painting with much stronger and more arbitrary seeming colour, though his Fauve harmonies were never as radical as Matisse’s. As with Matisse this use of colour was an attempt to get nearer the truth – the truth of light – not turning his back on it. Years later he wrote to Andre Lhote, “You refer to my struggle for colour, and rightly so, since all my life has gone into this. But I should like to be fully understood, and, to be quite sure that I am, I should prefer your saying, ‘my struggle for light’, which is the soul of colour. Colour without light is lifeless. What I have always been after is an order of colour, of physical colour as it comes from our tubes, an order that makes those tubes yield light. Without light forms fail to come to life, colour alone being not enough to make them stand out. We perceive light first of all, colour afterwards.”

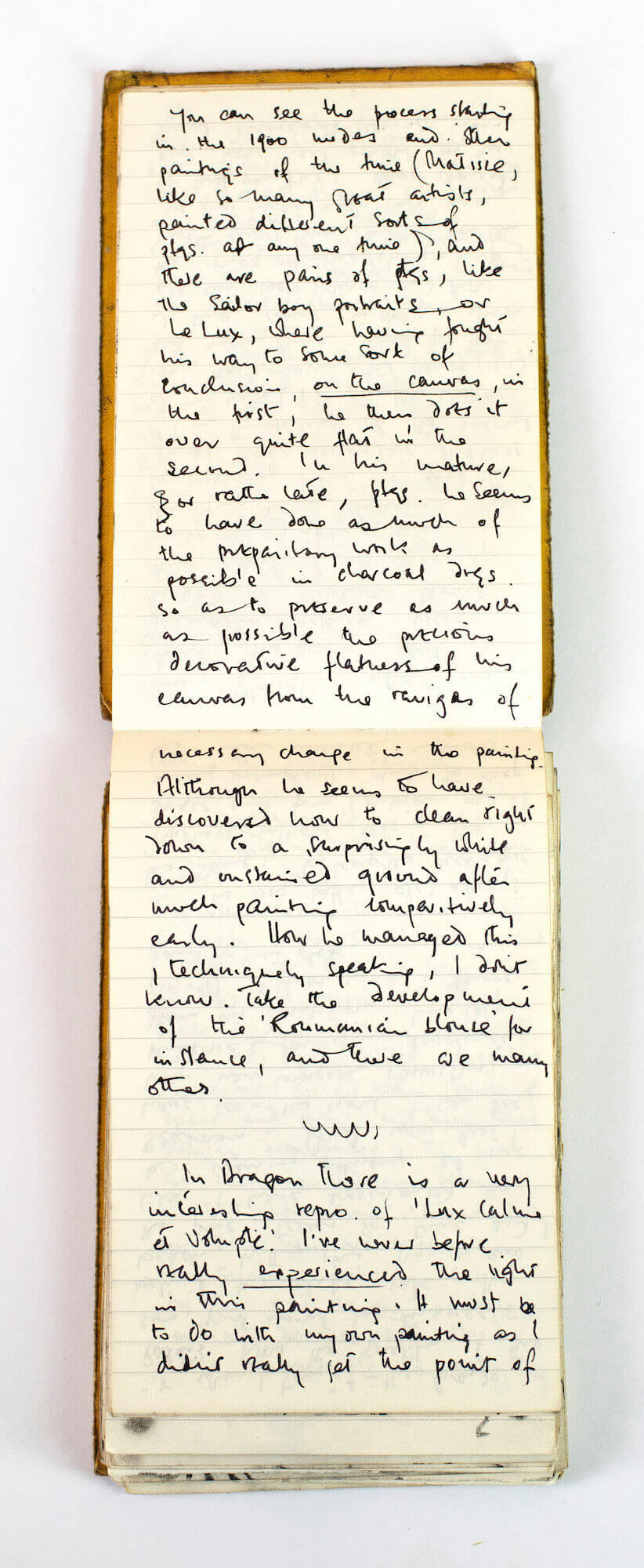

Fauvism only lasted a couple of years, but it did for colour what the influence of Cézanne and Cubism was to do for drawing, that is liberate its use in design from the constraints of “appearance”, leaving the painter free to invent whatever pattern seemed most powerfully to evoke his experience. 1907 was the year of the Cézanne Memorial Exhibition at the Salon d’Automne (and of Picasso’s “Demoiselles d’Avignon”). In 1908, Dufy and Braque went to L’Estaque, scene of so many of Cézanne’s heroic struggles, where they gave themselves entirely to a new way of drawing, of painting from nature. No bright colours in these fierce, uncompromising, difficult canvases (Dufy’s paintings did not sell and his dealer, Blot, dropped him). In “Le Port,” c.1910, we see Dufy learning all he can from Cézanne. The wonderfully sonorous colour creates brilliant sunlight (coming from left, and right, and behind!) and the pattern locks into the rectangle with a new almost physical (as opposed to optical) precision. Already Dufy’s interest in a much wider angle of vision is noticeable.

Cézanne brought line back into painting and this was probably his most important gift to Dufy for it gave him the most direct way of expressing his truly remarkable understanding of forms in space. Dufy had that rare ability (like Tintoretto. Rembrandt, Turner, Cézanne, Bonnard and Matisse) to look at a flat surface and “see” behind it as it were – in fullness and clarity, the space filled with forms that he had just been looking at (or imagining), so that to draw with a line – for it is an essentially linear comprehension – was just like reaching out to touch and move around or across the forms that were so clearly there in his imagination. It is this spatial imagination, this perfect sense of scale, of the size of things in relation to oneself and their distance away, that makes him such a fine architectural draughtsman, and makes him, with Turner, one of the very few artists able to give scale to mountains. “When you stand before a landscape motif, measure it like a surveyor and you will find that it may well have an area of many acres. If you add to that all the sky above your head, you get the extent of the area you propose to render on a very small patch of canvas. This is the problem you face…”

If you look at a pen and wash drawing by Rembrandt or Claude Lorrain, or a watercolour by Cézanne or Dufy, you see line and colour in counterpoint, like two instruments combining to make the one music. Line, the violin, perhaps, and colour, the piano. Mostly the line holds the melody accompanied by the colour. There are rich passages where they are thickly interlaced. Sometimes, one or the other plays alone, sometimes they play in unison. This quality lost from painting for so long but brought back by Cézanne was taken up by many of the twentieth century realists but nobody gave it such expression as Dufy. One day whilst idly watching a stroller on the pier at Le Havre, Dufy had a strange experience; as the man stopped for a moment and then moved, his colour mass seemed to detach itself for an instant from his form. This gave Dufy the idea of allowing line and colour to become even more divorced, especially when forms were moving.

Dufy was always trying to extend the expressive possibilities of the elements of decorative design – of line, of tone, of colour, of local drawing, and of the drawing of the whole, that is composition, and what he did was separate them more and more so that each could be used to the full in its own most powerful way, without any unproductive redundancy. If the relative importance of a form could be established by line alone, then there was no need to weaken the light and space (and emotion) giving possibilities of large areas of colour by breaking into them with the particular colours of that form, and when the colour of a form was sufficiently assertive to warrant doing this, it would make a far greater impact. “When you have a number of similar objects together, trees for example, don’t divide up shadow and light on each object, but make up whole sections with the colour of shadow and other sections with the colour of light. Take three oranges, for example; if you detect three colours, orange light, brown shadow and yellow highlight, make one of the oranges orange, one brown and the third yellow. In this way the sum total of shadow and light is the same as if you had portioned them out on each orange. Assume the proportion of light, shadow and highlight to be as follows: light 3, shadow 2. highlight 1: then on the canvas these proportions will have to be maintained by varying the size of the oranges.” ln the same sort of way he would represent foliage with broad areas of colour for its light and shade. and then draw leaf symbols over the top in line (different for different species). These lines set up optical vibrations which combine with the overall light-giving colour chord to evoke the diversity of light moving through the mass of foliage. He does the same thing with wave “signs” on the sea.

By separating the elements of his design into at least three modes: ambient colours, particular colours assertive enough to break free from the ambient colour, and line, each with its own different ordering within the whole, Dufy was able to tackle new subjects. “In spreading a local colour over all the canvas, I neutralise the object and this colour no longer personifies such and such an object. Thus for the other elements of the painting, I free myself from the restraint of imitation and the field is clear for the imagination of colour.” In the thirties he painted wheat fields and race tracks with passing showers, the whole spatial particularity of the scene going on within the simple vertical divisions of the canvas into blue, green and yellow. ln “Le Champ d’avoine,“ c. 1933, there is no passing rain but huge summer clouds are moving their shadows across the undulating landscape, and the sense of that which endures, and that which does not, is poignant. The almost invisible violet shadows stepping back through the yellow foreground are exquisite and reminiscent of Bonnard. This separation of linear drawing from colour also enabled him to tackle subjects of great complexity such as the race tracks that he enjoyed, where the intricate weaving of horses, jockeys, owners, trainers, punters, mostly moving, among stands and track, and paddock and trees, were all presided over by the indifferent light and weather. In late life, Dufy turned against these paintings, because of their extreme popularity with people who liked their “subjects,” but “did not see them.”

Dufy had prodigious decorative talent but he was also highly analytical, and he did not like things that came too easily. Possibly because of this he painted with his left hand even though he was right handed and, it seems, could not write left handed. To Dr. Homberger, the American specialist who treated Dufy’s arthritis, he wrote, “I apologise, dear doctor, for not having written in my own hand the reply to your letters. I paint easily enough with my left hand, it’s an old habit, with my right hand I write, clumsily. In his Notebook he writes, “One must always break something to be true and alive, break without violence, but with firmness; the thing that must be broken is the overworked form too well known and familiar to such an extent it has lost its signification, its symbolism. Inspiration is a guide that needs no control. If it leads us away from the classic forms, we must not be afraid to lose ourselves, for in the uncertain and unknown lies part of the looked for treasure. We must not let our taste turn us away from our adventure; let us rather use it to enjoy the beauty in the works of others, but for our own work we must not use it for it would incline us to moderate our inspiration, to choose, instead of sending us headlong down our path.”

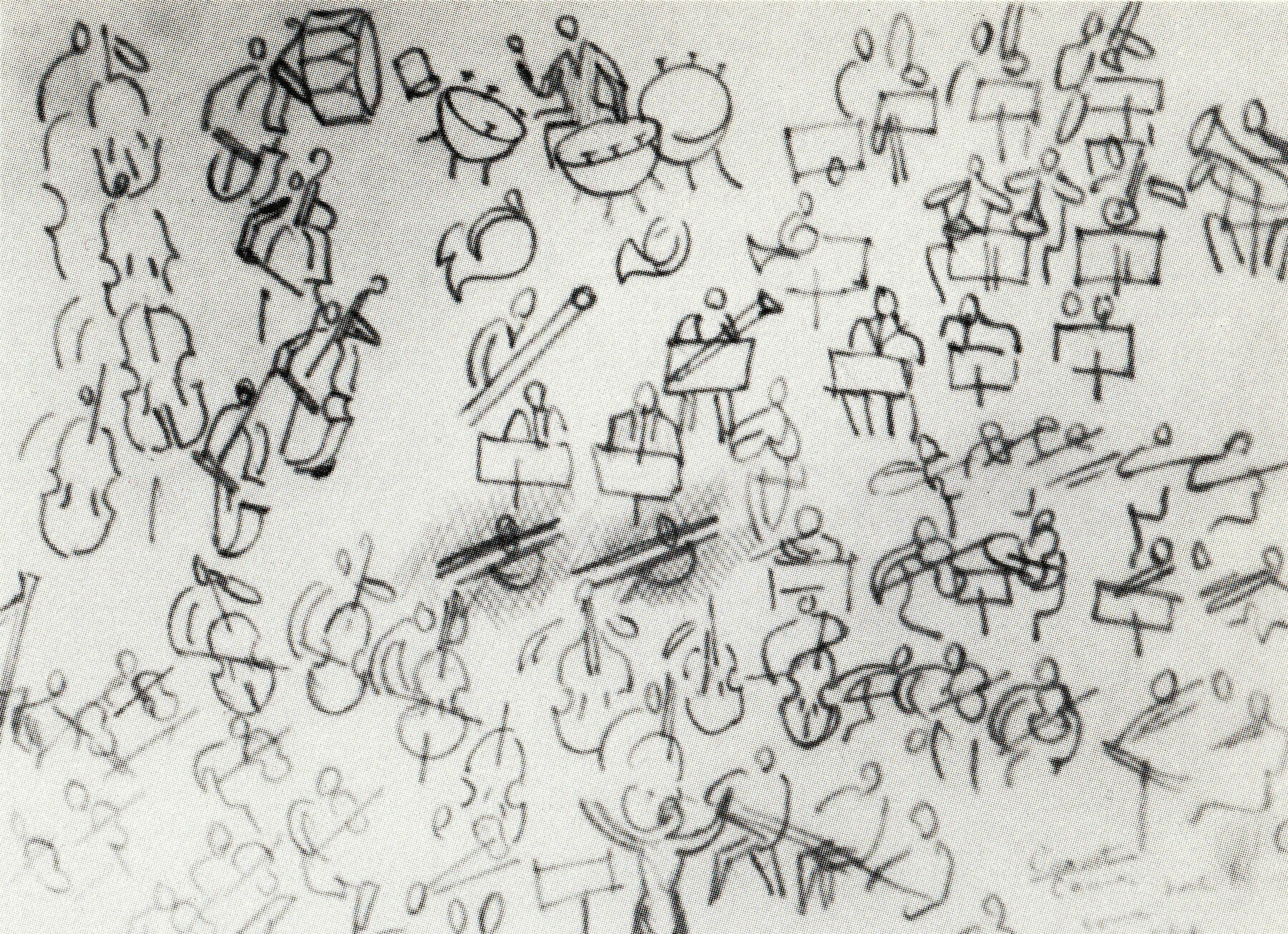

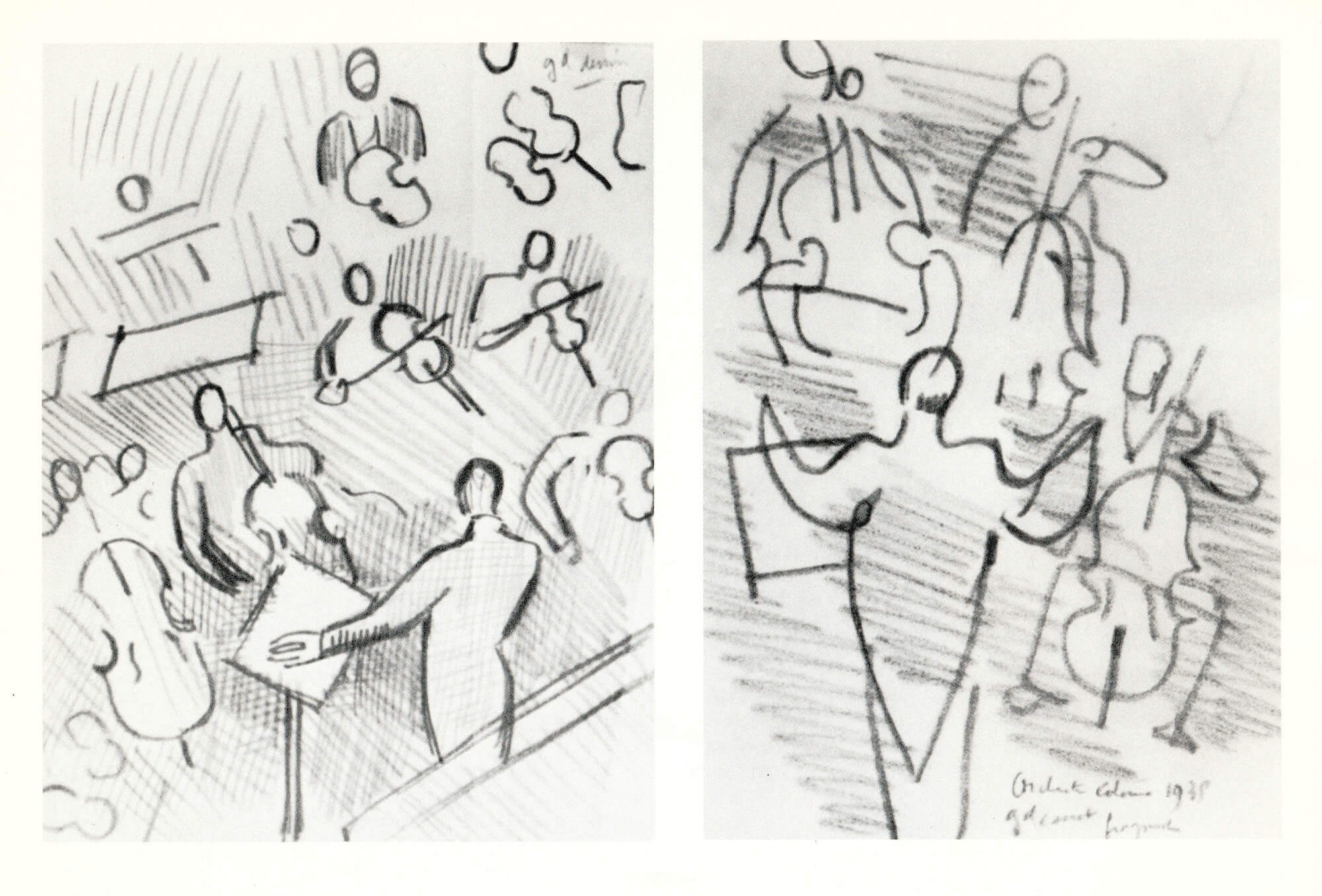

In 1938 Dufy had his first attack of the arthritis that was to dog the rest of his life, leaving him unable to paint at all for quite long periods. In 1940 he moved to Perpignan, away from the German occupation, and to where the dry climate was good for his arthritis. In 1942 he painted many canvases of his studio there (I assume from direct observation; his normal practice was to paint from drawings, watercolours and memory), and began his paintings of orchestras and chamber groups for which he had made hundreds of drawings at rehearsals in Paris before the war. Music had always been a part of his life. His father played the organ, and all eight children played an instrument – Raoul, the violin. “Imitate the main theme and the timbre of the instrument playing it, which stands out against the overall sonority of the orchestra, by imparting a particular light effect to a group of instruments and giving it a peculiar form and stamp that have nothing to do with the instrument or players, but which stand as an abstract sign interpreting the music at a given passage. We can see this in practice in “Orchestre a la Pianiste.” The rearing conductor, pianist, and leader are locked together in design and we know the horns are to the fore, also the flutes. But look at the three cellists, the indescribable richness of their colour the blue reflections tell us it is a daytime rehearsal – and the lines making their generous resonating volumes, soak into our eyes to make … sounds! These music paintings were the most extreme extension of Dufy’s pictorial language.

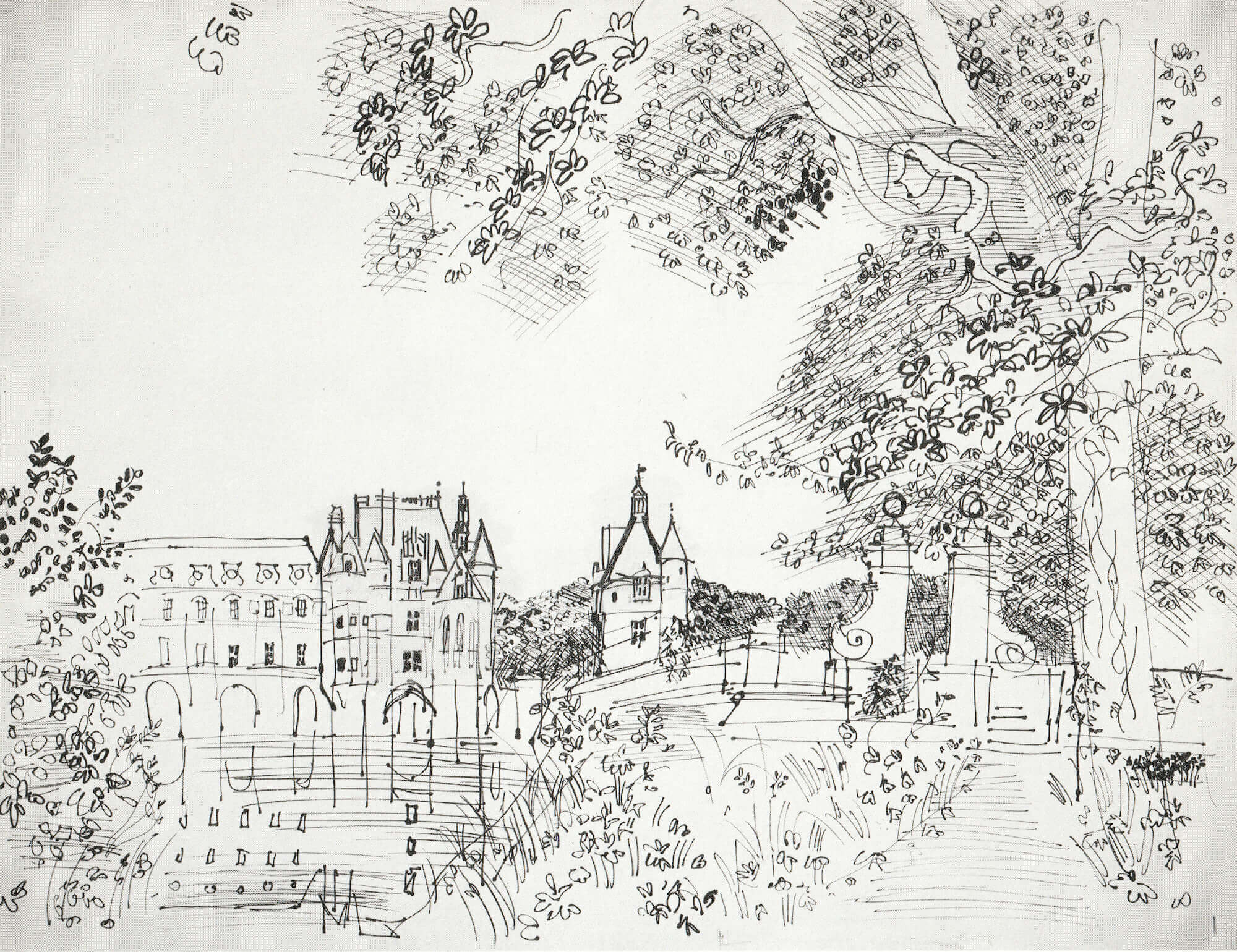

From 1910 onwards, Dufy was an active designer as well as a painter. He illustrated numerous books, and until 1925 designed textiles for Poiret and Bianchini. He was also personally responsible for revitalising tapestry weaving for which he made many large and wonderful designs. The drawings, watercolours, oils, and designs in this exhibition are some of the fruits of a great artist and we are very lucky to be able to enjoy them here. Look at the drawing of Suzy Maze. It is so marvellously the portrait of a whole person; of her hands holding a pencil (is she drawing Dufy?) as much as her head; of her plump little body and just how it wears her dress; of the dress itself, the one she chose, and it is all so French. One day when Dufy finished a portrait he said to the sitter, “Now go home and try to look like it.” “Chenonceaux,” is one of his Chateaux series, drawings which revel in the ink marks made by a steel pen. Looking at this drawing you can almost hear the pen’s progress as it whistles and snatches and snags. This delight in his medium, and in its intransigence, is so completely at one with his delight in being there, that every time our eyes are held for a second by a surprisingly fat and liquid line, or a razor grid of hatching, we experience with increased intensity the look of a turret against a summer sky, or reflections seen through water seen through grasses. Dufy drew and painted wider angle views than anyone (except possibly Bonnard), and although this drawing is not extreme in this respect, the pull to the extraordinary knotted branch of the plane tree high above our right shoulder could give one a crick in the neck. We are back where we started: being Dufy. “Painting,” he said, “is seeing for other people.”