William Bailey

The Century Club, New York

2018

Through June 1, nearly forty of William Bailey’s quiet works from two decades are on view in the Century Club’s smoothly skylit gallery. Despite stylistic differences, his figure and still life paintings share affinities with Intimist painting, whose objects “tend to take on the role of characters [and] people have the permanence of objects.” 1 Subtle tensions in Bailey’s oils and temperas between rendering and flatness play off those of saturation and temperature, resonant of Morandi. But observation informs Bailey’s only indirectly; his carefully remembered forms recall Morandi’s circumspect pittura metafisica more than the painterly empirical work.

In “Pianello,” a saturated, slim blue vase is pressed behind a beige bowl overlapped by a larger, precisely dulled orange urn. The complementary color drama, echoed by adjacent hues in supportive roles, stretches across the surface. Slowed by a bold enamelware pattern, composition extends toward a purpley gray background, where its temperature fluctuates against the ochres and blues.

Bailey’s fresco-like palette favors the unsaturated, where temperature resounds. In “Poggio Manente” the contest from opposing sides of the color wheel pushes a white dish to green against the warm reddish background, which then approaches purple beside yellows. Shapes again more or less expand from the grouping’s center; anchor-like, a flat blue stripe stills movement.

The invocation of scale contrasts is one reason Bailey’s sensitive still lifes keep their distance – notwithstanding the feminine genre’s “domestic iconography,” writes Bryson in his superb “Looking at the Overlooked.” 2 Landscape space is even conveyed when ellipses are flattened as though located at the horizon, rather than enlarging below it to reveal their interiors – and so intimating still life’s inherently proximal space, and thus bodily gesture. 3 Indeed, Bailey thinks of his still lifes “in architectural terms… like imagined towns.” 4 Their profiles suggest those of the Italian hill towns Bailey has regarded regularly since the 70s.

In the worldly “Turning,” an optimistic blue vase establishes eye level – yet ellipses below it lower, not increasingly as would occur in perception, but uniformly. An array of objects along a circular table at the bottom lies perpendicular to relatively huge overhanging rectangles of light and shadow, dwarfing them in a scale drama not unlike people to skyscrapers.

Interplaying sizes and volume of shapes vis-à-vis their color weights is perhaps the prime formal impetus here. Exploiting its position as “the genre at the furthest remove from narrative,” 5 the modern still life, discarding its traditionally lowly status, has had vanguard aspirations, evident in those of Cubists Braque and Gris. Bailey admits, “[A] narrative would have to be completely assimilated into the formal language of painting before I could use it in a way that would allow me the artistic freedom, honesty, and authority I need.” 6

Before teaching at Yale himself, Bailey studied there with Albers, whose color pedagogy has become fundamental to American art education. As a teacher Albers barely discussed tonality, 7 so key to the French optical experiments that impacted American modern art. Perhaps more influential than light, however, was Impressionist fracturing: the equity granted to light and shadow on the picture plane was extended to figure and ground, opening toward abstraction.

Bailey’s closed forms reflect another trajectory, that of Italian chiaroscuro (“light/dark”), crucial to neo-classical certainty, which modernists since Picasso (Léger, scuola romana, Rivera, Tooker, early Gorky and Guston, etc.) have also utilized. Advanced by Masaccio, Leonardo moved chiaroscuro in the direction of timeless, sculptural solidity – so different from ephemeral Impressionist light (or the emotive variability, thus temporality, of Rembrandt’s). Modeling forms from recollection, as Bailey does, is a modern echo of the mimetic drawing of plaster casts to build up a visual memory bank.

Bailey’s Piero-like forms are never weighty but engage the equivocal interface of flat shape to volume (which the Italian word forma encompasses). They are subject to the movement of light, but never swiftly. In “L’Attesa,” (“Waiting”) a woman’s shaded face gazes from the window. Light breaks dramatically on her body, though the transition to direct illumination along her parallel arms is incremental. Similarly, the light in “Night, Niccone Valley” behaves variously; a woman’s face, close in tone to the sky behind it, gives gradual way to her lightened body against a darker background, while the table’s cast shadow is strong and clear.

Never contentious enough to contradict, Bailey’s manipulations of light convey varying speeds of discernment – from near-certainty to conjecture and backward toward memory. “Empty Stage I” and “Empty Stage II” witness the same shifting shadows of a piazza within different geometric schemes and canvas shapes, conveying the passage of time metaphysically, a “nostalgia of the present” that stops short of melancholy. Bailey’s architectural forms and still life objects, like Mondrian’s colored rectangles, are types whose proportions can be adjusted to compositional requirements, as in those between the study “Studio in Rome” and larger “Imaginary Studio II (Rome).”

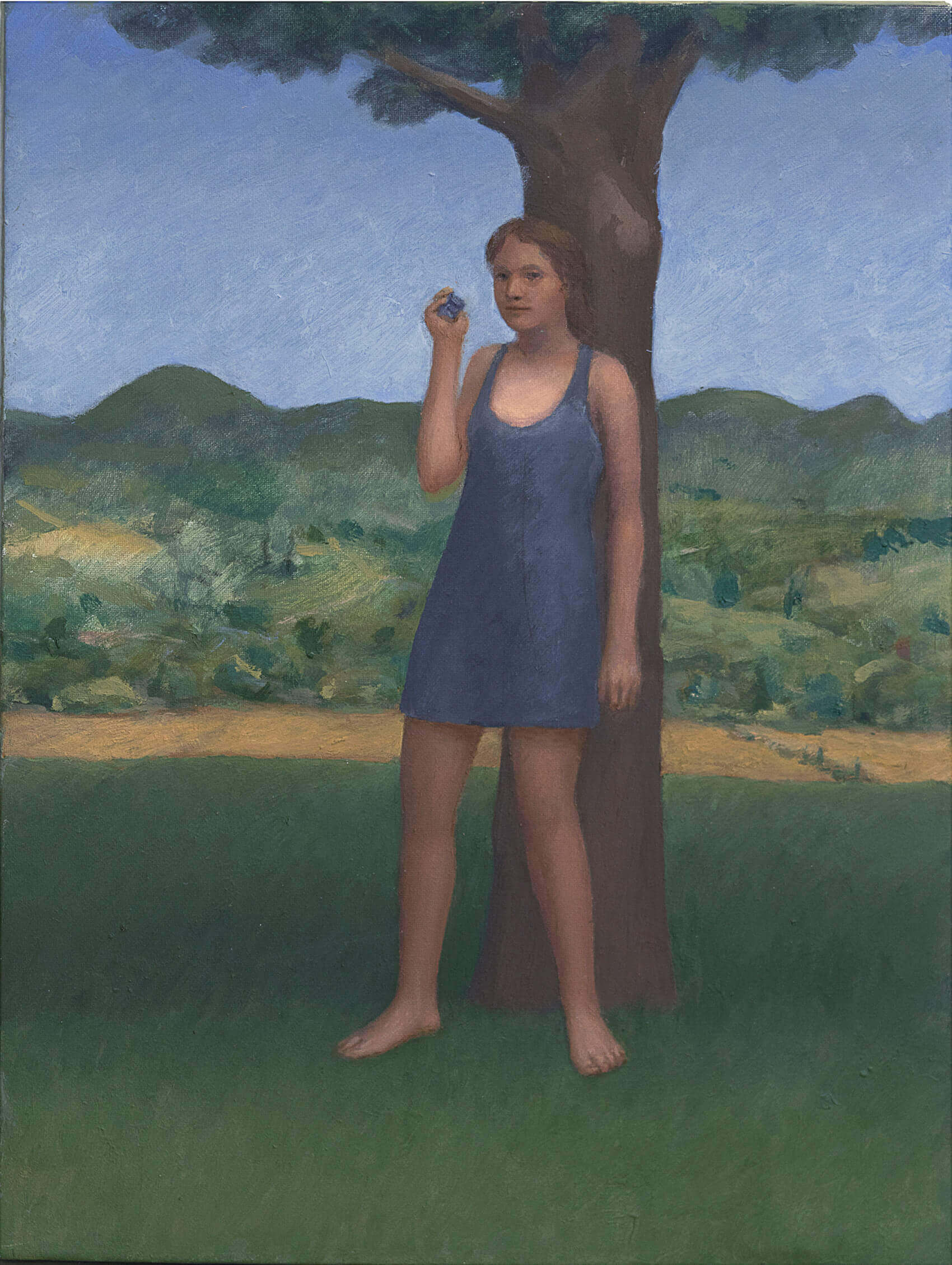

Figures’ proportions can’t be altered so easily, though anatomical liberty is taken in the relaxed rendering of the near figure’s contortion in “Afternoon in Umbria.” Bailey came to international attention as a figure painter through controversy in 1982, when his breast-baring “Portrait of S” made the cover of the widely circulated Newsweek magazine. Reminiscent of Balthus’s “Young Girl in a White Skirt” (1955) it’s more provocative than his usual figures, who disclose little and remain meditative even in confrontation, as in the iconic “White Robe”. Levity might give way to unbearable lightness, so humor appears obliquely in Bailey’s pictures, only overtly in attentive measure in “Cellular,” a small painting of a girl standing in the shadow of a tree, a tiny, cupped cell phone watchfully heeded.

Descriptive suppression, affective discretion, and technical subtlety may be why Bailey’s development survived the Cold War, when so much figurative art was considered slavish copying, if not potential totalitarian propaganda. Perhaps “mentally interesting to the spectator, and therefore usually…emotionally dry,” as Lewitt described conceptual art 8, is a safe tone for anxious times – a familiar return to the minimalist, aniconic bias of America’s Protestant fundamentalism, intolerant of Mediterranean excess. In any case viewers are now free to roam exhibitions with both figurative and abstract associations, without ideological guilt. Bailey’s poetic equivocations invite this in peaceful contemplation.

Notes

1 Robert Hughes, “Nothing if Not Critical,” p. 282

2 Norman Bryson, “Looking at the Overlooked”

3 Bryson, “…Still life is in a sense the great anti-Albertian gesture [opposing] the idea of the canvas as a window on the world, leading to a distant view… [It] proposes a much closer space, centered on the body… It’s “principle spatial value: nearness. What builds this proximal space is gesture:…of eating…laying the table, but also… the gestures which create the objects out of formless clay…” p. 71

4 Mark Strand, “Art of the Real,” p. 32

5 Bryson, p.9

6 Strand, p. 37

7 Strand, p. 16

8 Sol Lewitt, “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art” (1967)