John Walker: Recent Paintings

Alexandre Gallery, New York

October 2 – November 15, 2014

Tomorrow (November 15) is the last day to see an exhibition of recent paintings by John Walker at Alexandre Gallery, New York. If you haven’t seen the show yet, you should. On view are the latest in Walker’s series of plein air sketches and abstract landscapes.

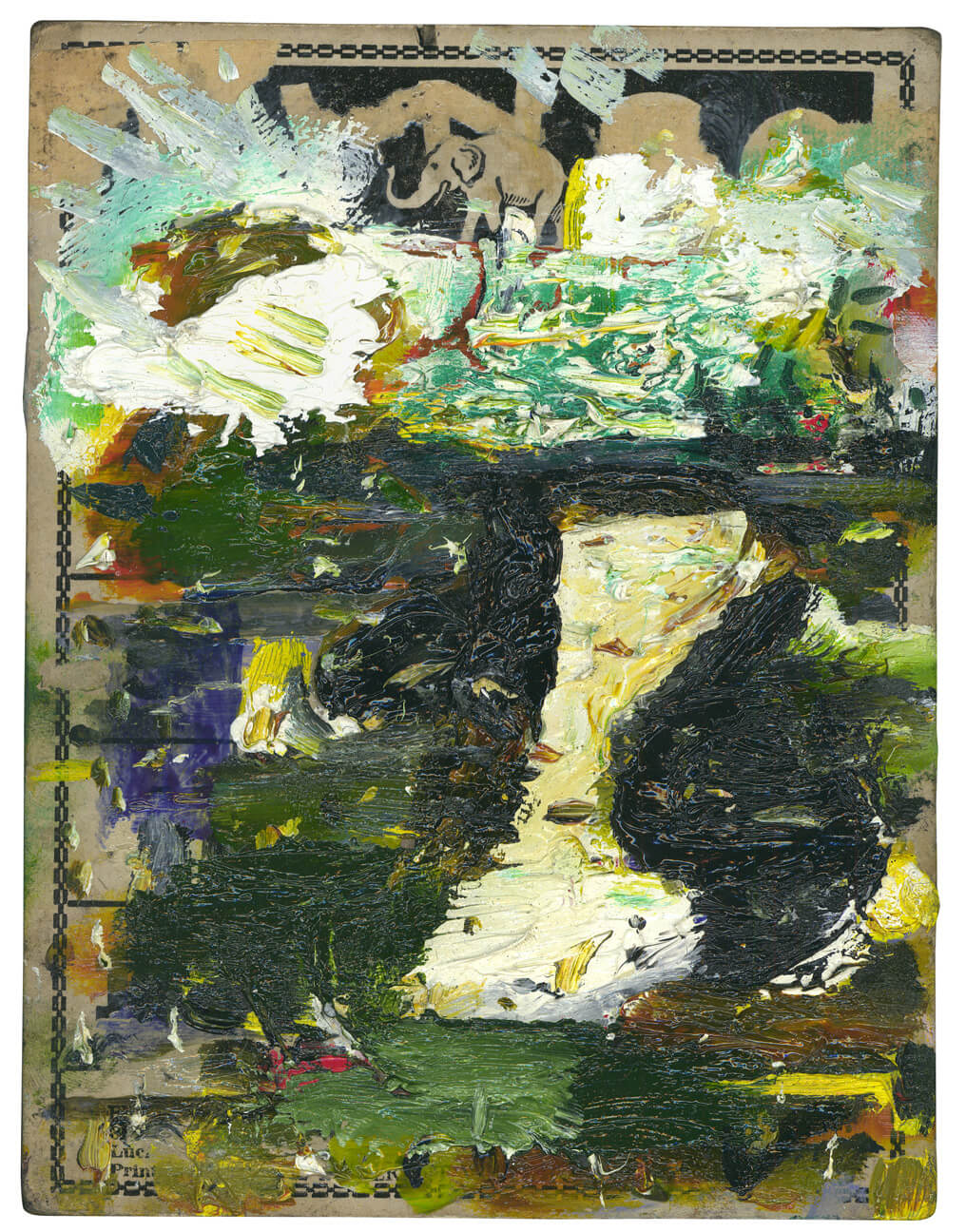

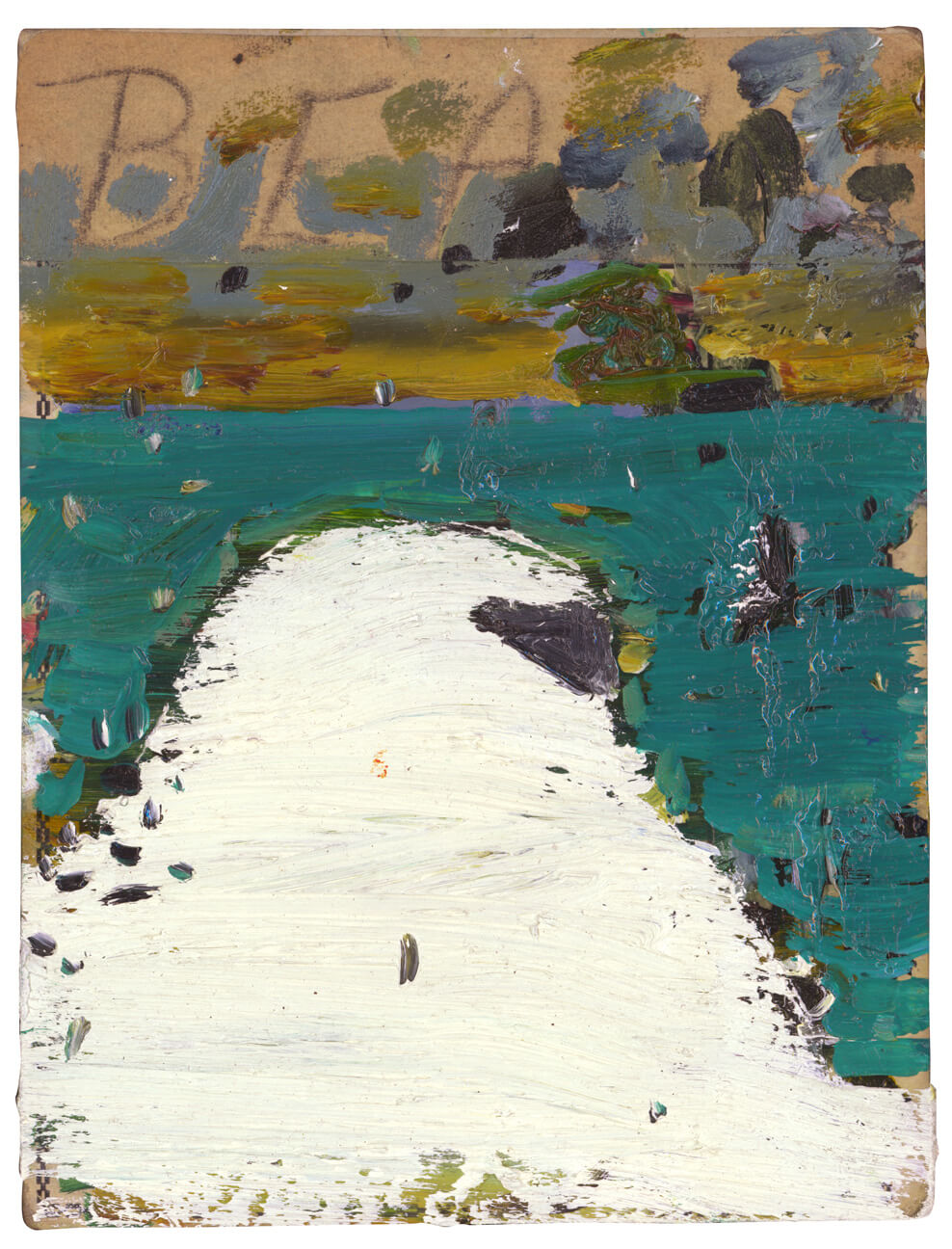

An ostensibly abstract painter, Walker has been painting the same spot in Maine for years, revitalizing abstraction through intense, prolonged immersion in nature. He has dirtied abstraction up with mud and salt air, exposed it to the rain, snow, and frigid wind. And with incredible results – never have abstract shapes been infused with such particular light and material specifics. Walker’s forms exist at a particular time on a particular day.

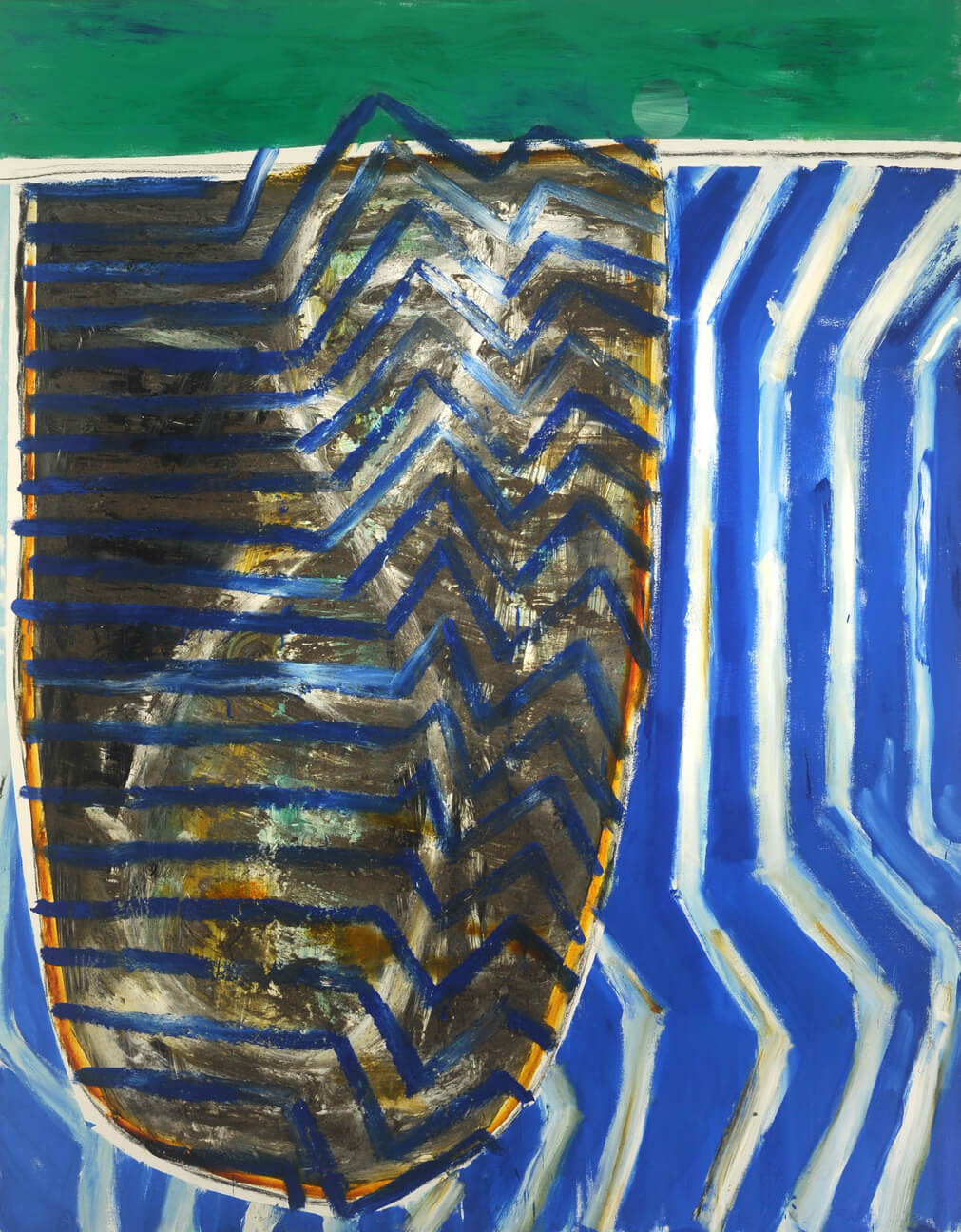

In each of the seven large paintings on view, Walker has distilled the major landscape forms he knows so well. Insistent, gestural jags dominate five of the canvases, merging the shimmer of light on water and the perpetual motion of the tides into a pure painterly energy.

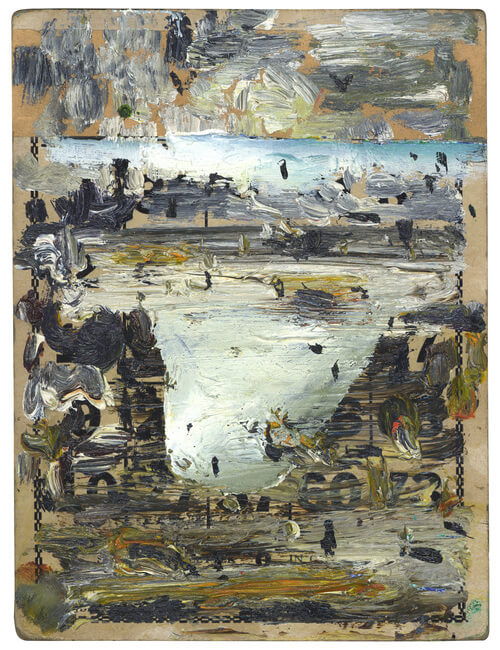

In Drift (2014), a figure 8 of light that suggests the reflective rim of a tidal pool, is overlaid with abstract horizontal and vertical shockwaves colliding like currents. The pattern is reversed in the adjacent picture, Brake (2014), suggesting a reverse flow out towards a brilliant yellow sky. A blue band at the bottom of the painting suggests the much gentler action of water lapping the shore.

Abstracted as they are, each painting is anchored by its horizon and an observational accuracy. In Island (2014), a true “dark sky” is evoked, dark enough for Walker to paint the color of the stars.

Any attempt to paint the Maine landscape inevitably raises comparisons to the work of painters such as Marsden Hartley and John Marin. Yet, Christopher Crosman, in his essay for the show, rightly identifies in this body of work a more significant dialogue with Matisse.

Crosman identifies a coloristic and rhythmic precedent for Walker’s new paintings in Matisse’s The Conversation (1908-12). True, but the relationship with Matisse goes further, Walker’s mood and method of construction also recall Matisse’s meditative Goldfish and Palette (1914) and The Piano Lesson (1916), both in the Museum of Modern Art.

To better understand the depth of the conversation Walker’s new work has with Matisse, it is worth quoting art historian Jack Flam at length. His commentary on Goldfish and Palette could describe almost verbatim a similar effect of any of Walker’s new large paintings:

“The whole of reality appears to be compressed within this mysteriously shifting space. The window offers only a stark blueness that calls to mind Stéphane Mallarmé’s azur––the all encompassing emptiness that underlies all the struggles of art and life. Within this sealed room, the still life represents not so much a kind of miniaturized nature but an ensemble of signs for things. The bowl, water, fish, plant, and fruit are rendered as compressed distillations of the things they represent. Moreover, these condensed images contain a surprising élan vital––in no small measure because of the the tightly sprung curves of the window grillwork, radiating out from the still life like abstract signs or the inner force of the objects.

It is not only objects that are translated into signs. The light itself is similarly transformed. The roles of black and white, the polarities of darkness and light, are intermittently reversed. The vertical black stripe that dominates the painting functions as a band of light as well as of darkness, and the whites that flank it also act uncannily as signs for shadow as well as light. Hermetic and introverted, this painting is perceived primarily as a projection of a state of mind. The fluctuant articulation of forms acts as a metaphor for thought.” 1

Compression. Loneliness. An “ensemble of signs” rendered with élan. Light transformed into vibrating visual polarities. A “fluctuant articulation of forms.” We need only change the still life references to those of landscape and Flam’s analysis applies to Walker’s paintings of Seal Point.

I believe it is also worth considering the achievement of these paintings in relation to Richard Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park series. Diebenkorn also paid close heed to the example of Matisse, but more importantly, he worked toward an art of pure abstraction sourced from observation. The light in the Ocean Park paintings is distinctively the light of Santa Monica, specific to the place the works were painted. Likewise Walker’s paintings, even at their most abstract, are characterized by an observational accuracy and attentiveness to place. The azure sky Walker observes in White Reach #2 (2014) blazes with a piercing northern glare. The abstractions of both Diebenkorn and Walker proceed from and profit by sensory overload.

Walker has stated that his original attraction to painting the tidal cove was that it was the place “where all the rubbish comes in.” 2 It is a place of action, of change, a constant influx of information. This influx of information is what Walker brings to abstract painting. Paintings like the cove are places of constant renewal. More than just a metaphor, his subject begs a question we as painters should all ask ourselves: is there enough stuff washing into our own paintings, not simply stuff off the mind, but stuff moved by the much greater force of nature?

What sets Walker’s “abstract landscapes” apart from others’ is that he pushes abstraction and perception equally hard; he allows them to grapple openly, each at full strength. The riskiness of Walker’s attempt to make a painting reverberate between the ruthlessly abstract and well-seen is clear, but so are the rewards. His work makes a convincing argument that painting can have it both ways, which is to say that the total potential of painting can still be employed to achieve a unified whole.

When I look around I see much abstraction that has become overly cerebral, or else influenced by distracted experiences of the world. Many insist that these are the only true experiences of our time, the only true things left to paint. But John Walker’s paintings remind us that other experiences of the world still exist, and can be painted. His canvases remind us we only need to walk outside and look around to find them. It is possible, and perhaps vital, to get away from the machines and the media, even escape from the studio. Painting is not just in the head. Artists have bodies that exist in space, legs on which to walk about. They have arms that reach out, skin that prickles in the biting cold, eyes that can be dazzled by the cobalt illumination of Maine in full sun.

Notes

1 Jack Flam, “Time Embodied,” catalogue entry in Matisse: In Search of True Painting, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012, pp. 82-83.

2 Beer With a Painter, John Walker, Jennifer Samet, Hyperallergic, May 18, 2013.