Faust and Other Tales: The Paintings of Jan Müller

Lori Bookstein Fine Art, New York

May 3 – June 23, 2012

A career shortened by an early death and a vision that flowed against the current of art history have undermined the contributions of painter Jan Müller (1922-1958). Banished from the official narrative, Müller is likely a to remain a footnote to the history of the New York School. Thus, an exhibition now on view at Lori Bookstein Fine Art in New York that showcases a number of Müller’s mature, large-scale paintings is a welcome, if short lived, opportunity to see his monumental Abstract Expressionist allegories.

Müller accomplished what more well-known New York School artists, Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko (at least in their early careers) could not – he made paintings that embraced myth and allegory while engaging issues central to the most forward-thinking painting of the time. While Newman and Rothko abandoned their mythological paintings of the early 1940s to pursue a purely abstract visual language, Müller took the opposite course. He renounced pure visual abstraction concluding “the image gives one a wider sense of communication.” 1

Müller remained a painter of abstract ideas, however, if not abstract forms. Without backsliding into still life or portraiture, he used allegory to address the question central to New York School painters: does an artist need to be a purely abstract painter to be “original?” 2 His paintings are original precisely because they take this question as their subject.

Müller’s allegorical paintings of Faust and St. Anthony are ultimately chronicles of his and his contemporaries’ struggle to create a new art.

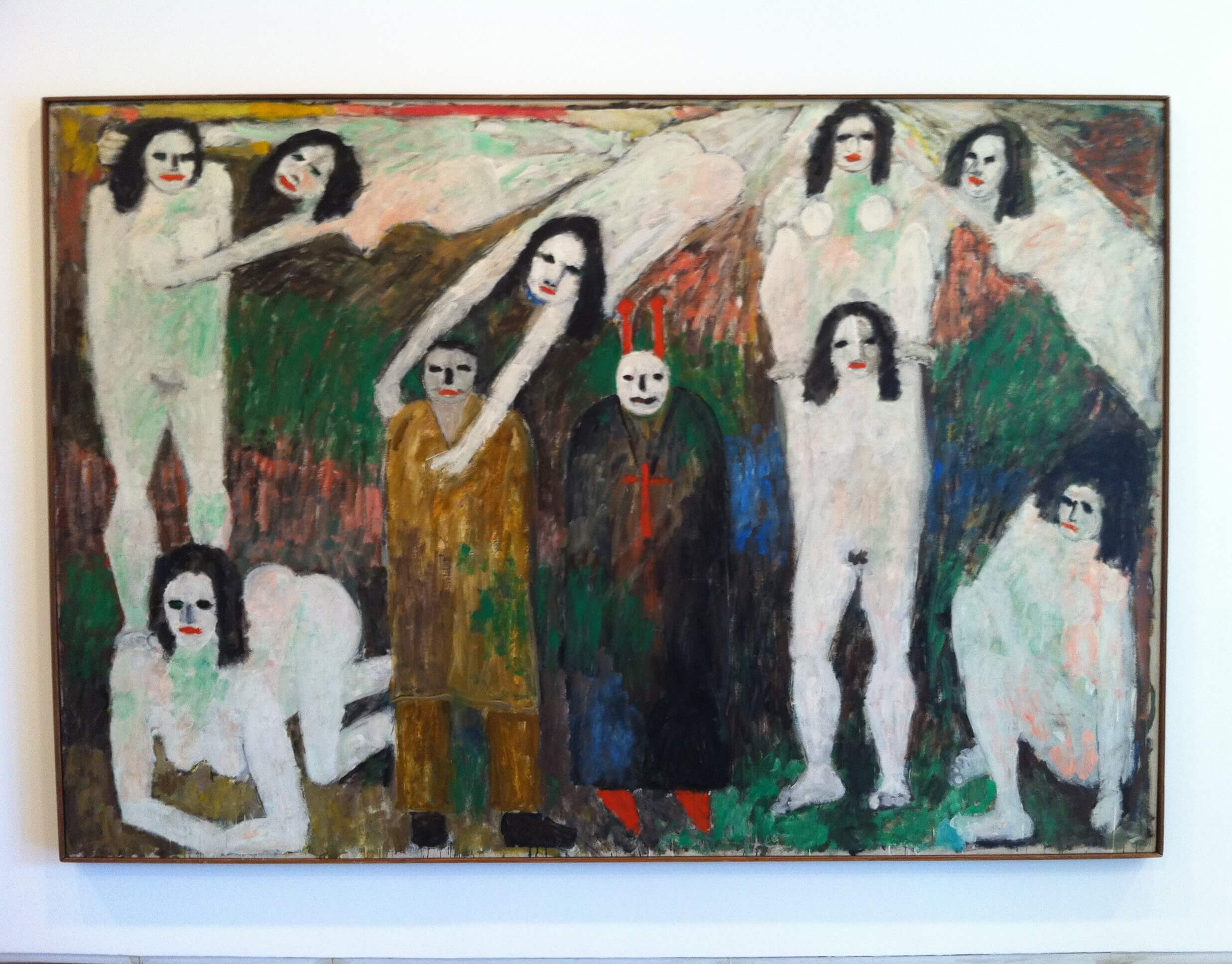

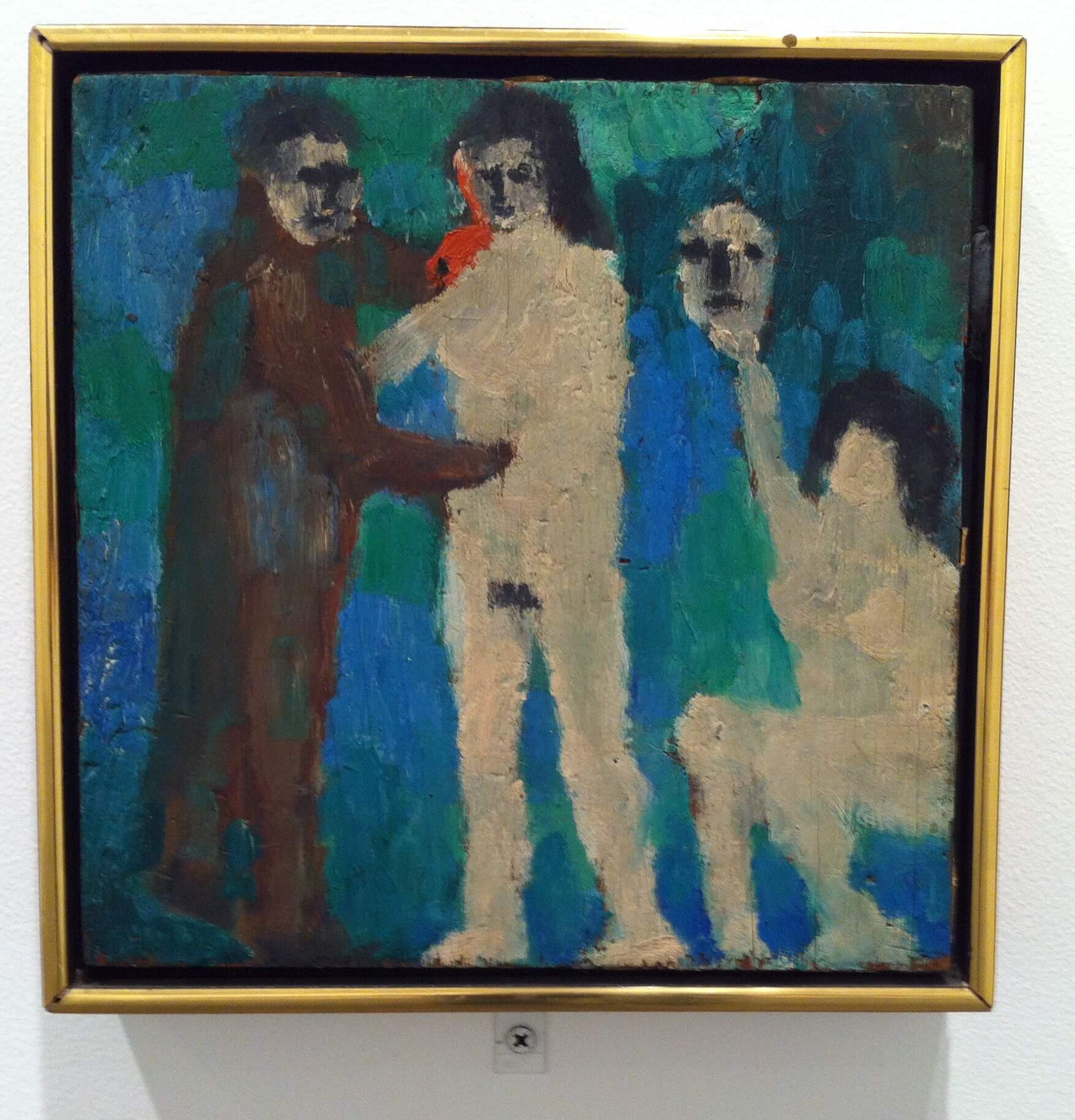

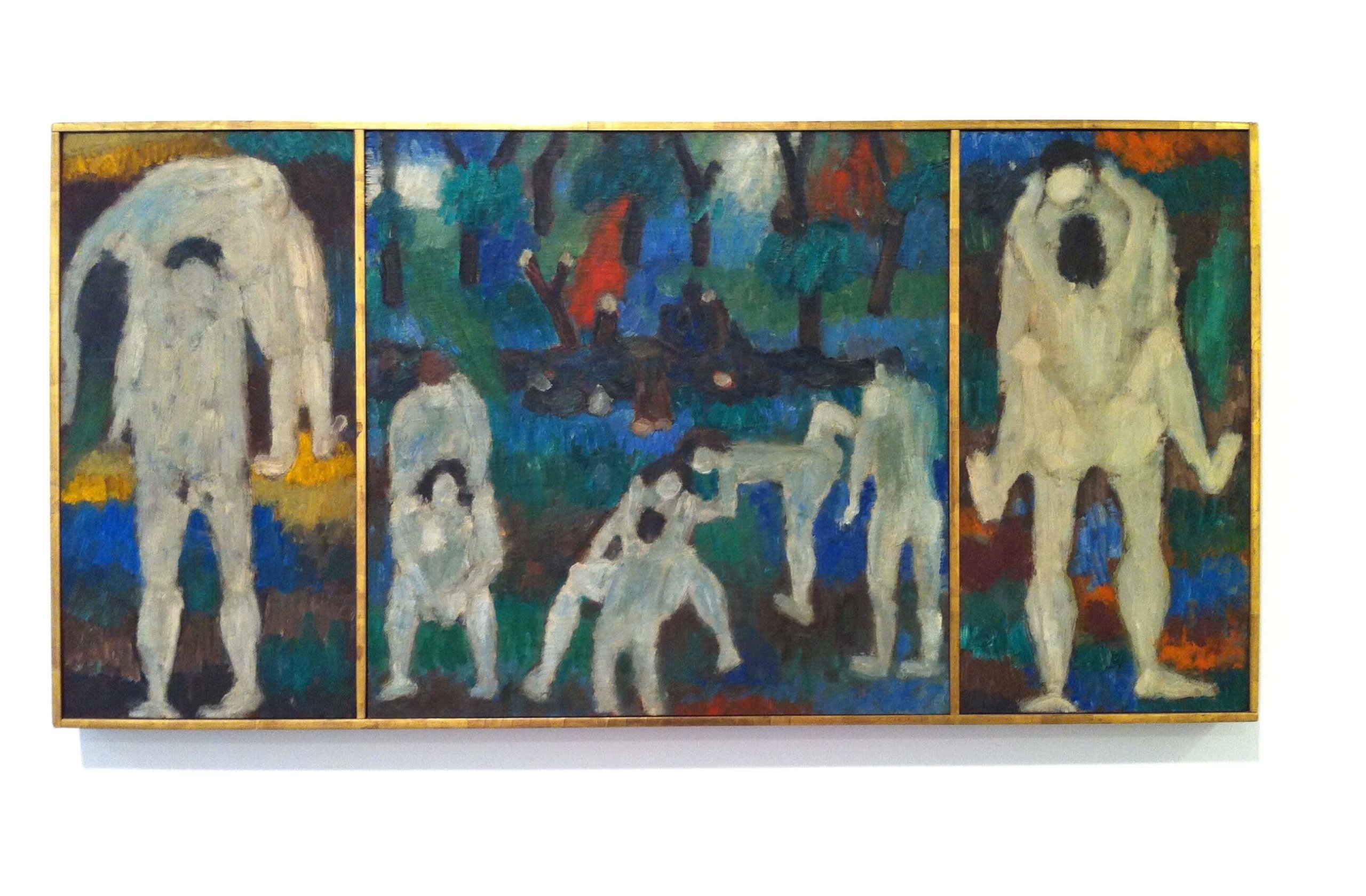

Müller first explored the potential of various legends to embody the struggle of the studio in smaller canvases, settling on Faust and The Temptation of St. Anthony for his grand scale works. Of the large paintings in this exhibition, Walpurgisnacht-Faust I sets the stage for Müller’s argument. The canvas is populated by simply but clearly modeled figures. They surround and protect Faust from Mephistopheles who, clad in black and wearing a red mask, lurks at the extreme left of the canvas. A single female figure at the opposite corner somewhat ominously lifts a green mask, revealing her face to be an orb of white paint.

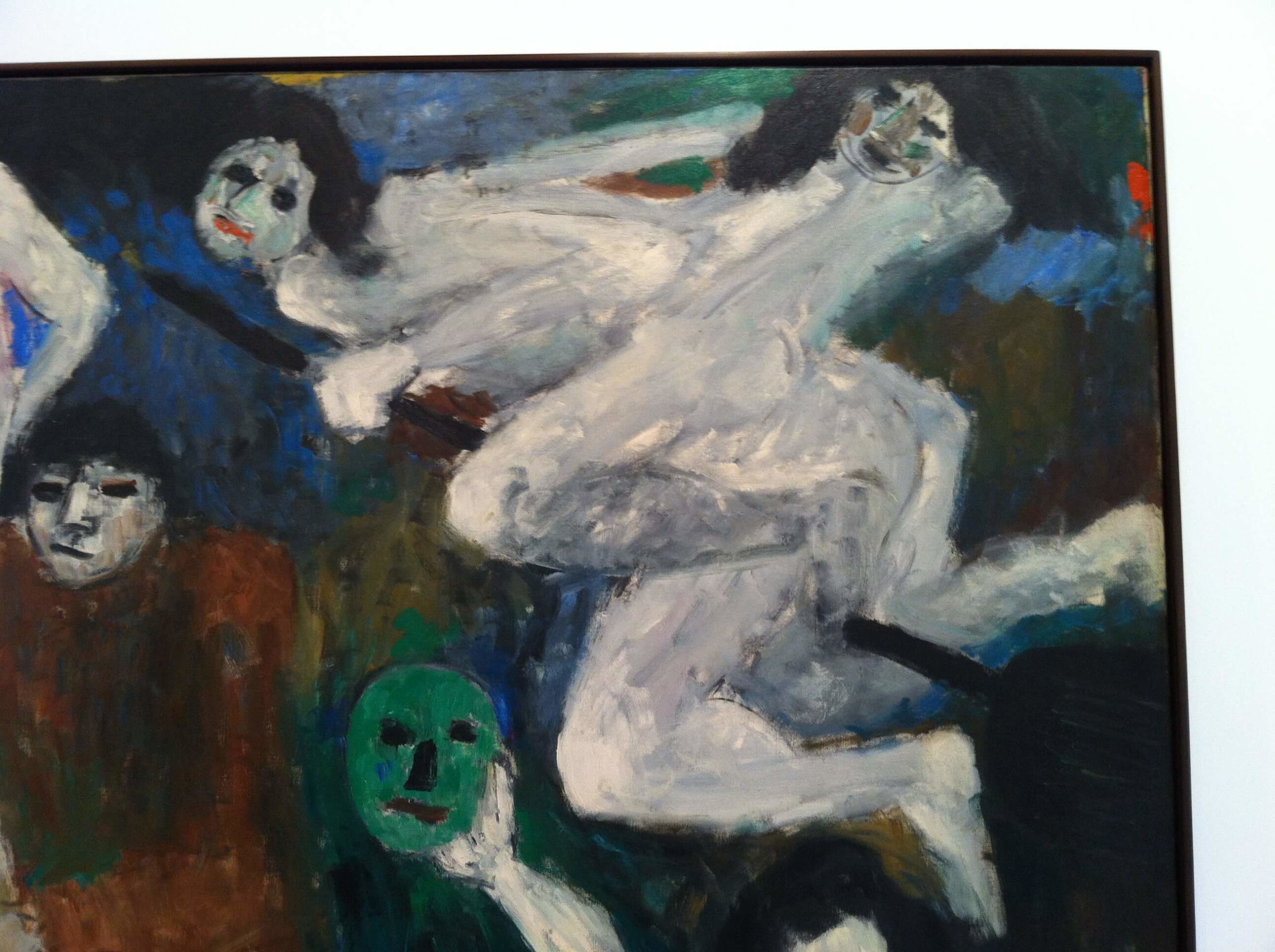

In Müller’s Walpurgisnacht-Faust II the figures have transformed. Now clearly a gaggle of witches, they enact a Matissian dance around the edges of the canvas. The witch figures are now primarily gestural; their sprawling bodies engage the edge, supporting the rectangle. They define the picture plane while simultaneously cordoning off and defending fictive space. They establish the possibility of the window while upholding the potential of the plane.

Mephisto now stands with Faust in the center, the heart of the painting. Müller’s Faust is now quite clearly a painter, his umber cloak streaked with paint, but he is less human. His body (and Mephisto’s) are less articulated – they are becoming abstract shapes. The female figures, too, are losing their identities as individuals. The entire scene is becoming ever more hieratic.

The last grand canvas, The Concert of Angels, does not bear the Faust title but seems to complete the cycle. A single figure in black with a dunce cap is surrounded by a chorus of figures, now completely stylized, described by simple blocks of color. Their flickering, rhythmic arrangement suggests harmony, yet a single female figure (perhaps Faust’s Gretchen) looks on, equally at home in the painting, supported by a kneeling red figure. Ultimately Müller’s painter, like Goethe’s Faust, is saved rather than damned.

To jettison the figure was a more traumatic issue for the Abstract Expressionists than official narratives convey. De Kooning never abandoned the figure and Pollock and Guston returned to it. Clyfford Still secretly continued to paint figuratively but chose not to exhibit the work. 3 Rothko might have found solace had he not felt his rejection of figuration to be irreversible.

For New York School artists of the 40s and 50s, the canvas was a battleground. As Harold Rosenberg famously noted:

the canvas began to appear to one American painter after another as an arena in which to act – rather than as a space in which to reproduce, redesign, analyse or ‘express’ an object, actual or imagined. What was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event. 4

Müller’s paintings, however, prove the event could, in fact, be pictured.

Müller is often grouped with other figurative painters from the 1950s including Fairfield Porter and Bob Thompson – painters who married abstract expressionist technique and earlier influences, most notably the Nabis. Müller’s vision and pictorial interests, however, align him squarely with Newman, Still, and most of all Rothko. Müller, like Rothko, embraced the canvas as separate from the world – a meditative space defined by color. Even Müller’s hushed brushstrokes, though drier and less sensuous than Rothko’s, evoke a similar weightless state.

In painting the classic tale of the deal, Müller stands alone in his portrayal of the artistic dilemma of his day. To view his paintings is to better understand The New York School. His allegories successfully and uniquely resolve figurative and abstract impulses. Müller’s vision, unlike most of his contemporaries, was generous enough to support both.

Notes

1 Jan Müller quoted in Judith E. Stein, “Figuring Our the Fifties,” The Figurative Fifties: New York Figurative Expressionism, Newport Harbor Art Museum, 1988, p. 41.

2 Robert Motherwell noted that the purging of the figure was the mark of originality saying that Clyfford Still’s paintings were “the most original. A bolt out of the blue. Most of us were still working through images… Still had none.” Quoted in Dean Sobel, Why a Clyfford Still Museum?, Clyfford Still Museum Inaugural Publication, p. 31.

3 Clyfford Still painted a traditional portrait of his mother (PH-420) in 1946, the same year as his breakthrough exhibition of completely abstract paintings at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of this Century Gallery. Still Life: Clyfford Still Museum Blog, http://clyffordstillmuseum.org/blog/happy-mothers-day

4 Harold Rosenberg, “The American Action Painters,” The Tradition of the New, Da Capo Press, 1994, p. 25.