It’s Sunday August 26, 2018 and 82 degrees Fahrenheit at 2 PM – sunny with a slight breeze. I’m back in Park Slope, Brooklyn walking toward Janice Nowinski’s studio. I always feel nostalgic for fall 1995 when I’m in Park Slope. That was my first season living in NYC after undergrad in Chicago.

The tree lined streets, brownstones, and Prospect Park haven’t changed much but the neighborhood feels different. The way a painting can feel different year after year, making a person aware by contrast of how he or she is growing and changing. Janice was here working and living in the same studio and apartment that she’s in now for a long time before I arrived. Maybe we passed each other on the sidewalk, ate in the same restaurant, or rode next to one another on the same subway car at some point in ‘95 or ‘96, but we didn’t know each other then.

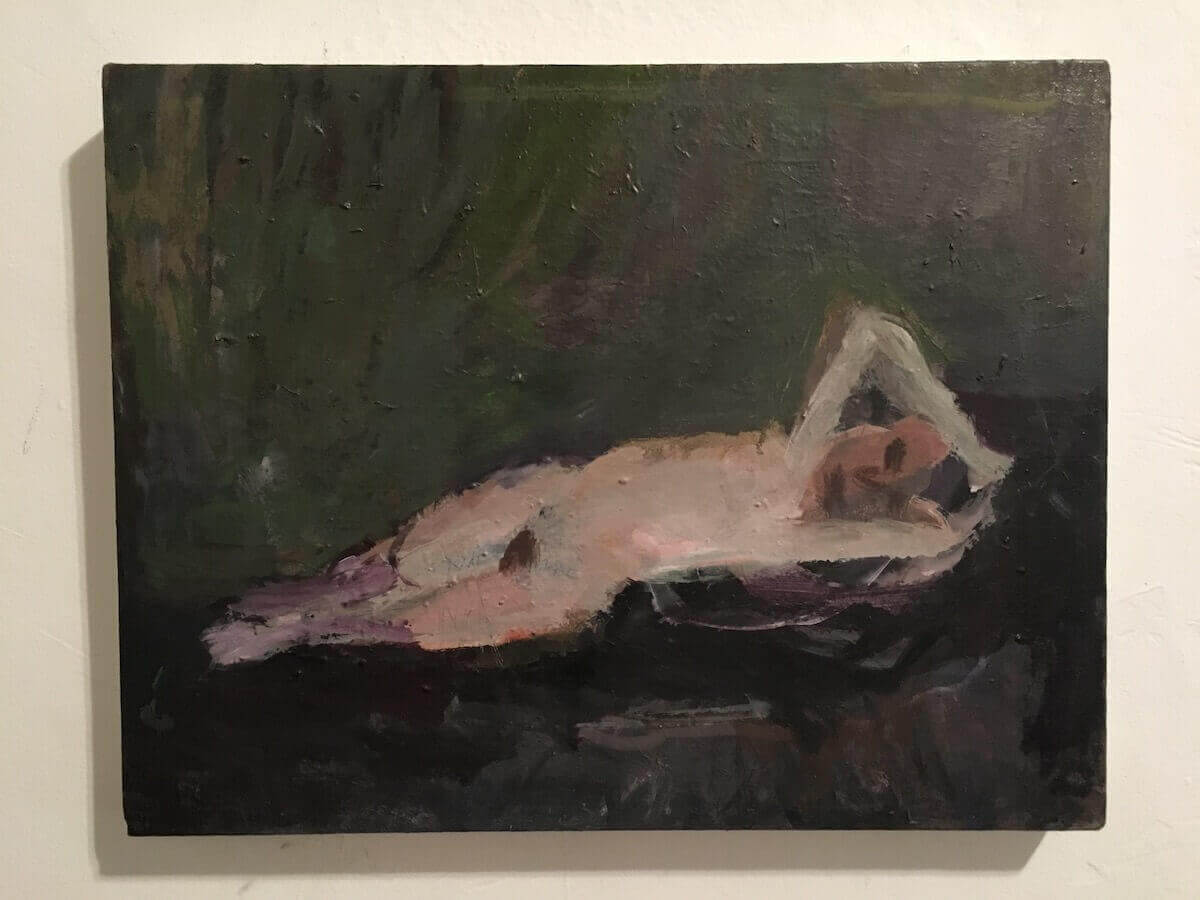

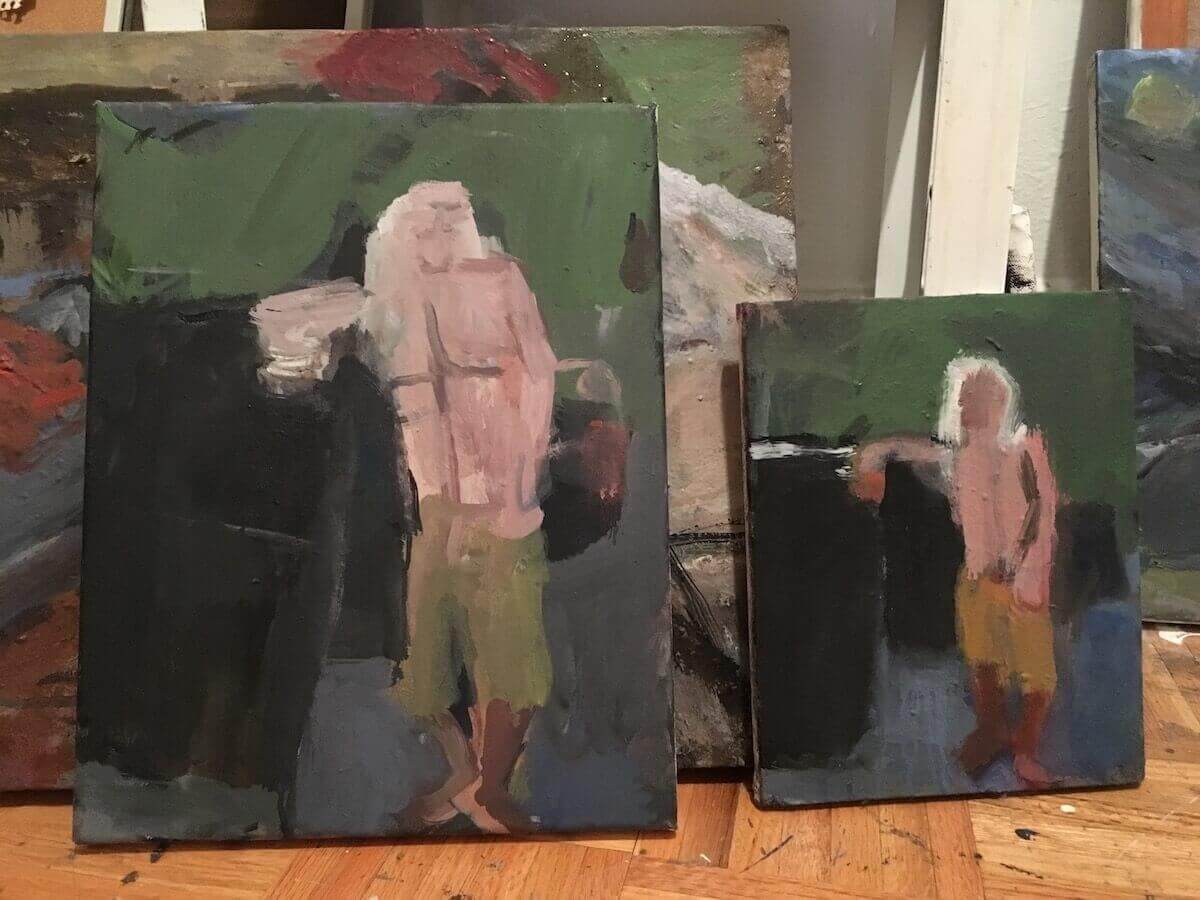

The sensation of 23 years gone and all that has happened in that time brings a feeling of pathos to this sunny Sunday afternoon. I find similar qualities in Janice’s paintings. They’re heavily worked, contemplative and dark while at the same time relaxed and optimistic in feeling – like a midlife, slightly melancholy, sunny breezy late-summer Sunday afternoon.

John Mitchell (JM): Janice, where are you from and how did you get into making paintings?

Janice Nowinski (JN): I grew up in Rockaway, Queens, near the beach.

My Uncle Bill, our family violinist noticed that I had no particular idea of what the hell I was going to do after I graduated from high school at the age of 17. His suggestion that I go to violin-making school in Cremona, Italy was embraced enthusiastically by my entire family.

While taking a crash course in Italian in preparation for Cremona, it occurred to me that perhaps sculpture skills might come in handy so I enrolled in a sculpture class at the Brooklyn Museum art school.

I never did learn Italian but I lost my heart and found my path at the sculpture class.

The following year in violin-making school may not have resulted in me becoming a violin-maker but it enforced my desire to pursue art.

I was back in Brooklyn a year later to see if it really was love. It turns out that it wasn’t sculpture that had my heart but its cuter brother Painting that I would end up spending my life with.

I rented an apartment in Brooklyn and turned it into a studio. I’ve been there ever since.

JM: So then you went on to study painting? Who were some of your most influential painting teachers and were there any particularly meaningful or memorable lessons learned in art school that you could share?

JN: I arrived at the New York Studio School looking for direction after a confusing year and a half stint at the Art Student’s League.

Having been painting on my own for a few years, my master plan was to pick up a few techniques and get out of school as soon as I could. I didn’t want to waste any time. I happened into Gretna Campbell’s painting class and my master plan quickly changed.

She came to my studio once a week. Sometimes she said nothing. But the previous week she had lauded a painting that I had been working on. I continued energetically working on it with high expectations of what Gretna’s response would be and looked forward to hearing her continued admiration for the vast improvement that I made on it during the week. Her silence that following week should have clued me in that perhaps it wasn’t going as well as I thought and that maybe she lost her admiration for this painting. But being an ever-hopeful art student, I just had to have her voice her opinion. She said, “You ruined this painting, there’s not much else to say”. I asked her to explain, “you painted the exact same thing on top of last week’s painting and in doing that you smothered the life force out of it.”

Lesson learned: You can’t put your foot in the same place in the river twice.

When I first was in Gretna’s class, I would hound her for tips and techniques. She finally told me that she could not offer that. All she could help me do was to recognize my own voice if and when it arrived in my painting.

I had picked up at the NYSS that I should NOT paint literally. I was not supposed to copy what was in front of me but to interpret it. In class there was a set up and you painted from observation. You looked at something tangible but responded in paint with abstract concepts of shape, form and color. Through the process of recording observations, extracting and editing, a distillation took place. The idea being that your own voice would show through by what you honed in on or what you chose to leave out.

When I arrived at Yale grad school my paintings were neither fish nor fowl. Again, no techniques or systems were taught. As William Bailey said, “Painting cannot be taught.”

I had the great fortune of having extraordinary painters in my studio who spent time looking at my work and telling me what they observed. The observations were pretty nuts and bolts, not intellectual at all.

I was making still life paintings of pears and bottles in an “abstract/non-literal” way. There were blocks of color that were supposed to represent fruit. Andrew Forge came in and said, “You are painting pears but to be honest I don’t see a pear shape.” That question stunned me and to this day, I am still mindful of it.

Another question that haunts me was delivered when Jake Berthot came to my studio and asked why I had pieces of bottles floating around in my paintings. “Bottles in or bottles out.” said Jake. He showed me Milton Resnick, who I took to be “a bottles out opter” and this scared the hell out of me. I couldn’t do that. Morandi – the quintessential “bottles in guy” wasn’t a viable option for me either. I would have to negotiate the land between “bottles in and bottles out” and stake my own claim in this territory. This realization was the beginning of my life in the studio.

To this day I am grateful that I stumbled into the NYSS at the time that I did. It provided an atmosphere, which allowed me to imagine and invent my life as a painter. The school had 24/7 access to the studios, visiting artists ranging from Robert De Niro Sr. to Julian Schnabel and a big slop sink. One of my happiest memories of art school was listening to the dean, Bruce Gagnier, in a darkened room – talk brilliantly and passionately about Goya and Corot while clicking through a million slides that he had hand picked from the Met Museum slide library.

JM: I see a hand palette encrusted in mounds of paint with a small clear area and one small brush. Can you talk about your painting tools including the palette, brushes, colors, and paint that you use?

JN: I suspect that most painters are creatures of habit. I certainly am.

The first palette that I had was probably within a few inches of the same size as this one. I’ve been using the same size palette since the beginning. This probably correlates to the scale/size of my paintings. On the rare occasion that I do a larger painting I am forced to use larger brushes and a different palette system.

I do like this one brush, a size 10 sabeline by Raphael Karrell. I have about 5000 of them! I use them until they shred and then break a new one out. I like the things I can do with the brush as it deteriorates. Sometimes I use a deteriorated one and a new one at the same time while I’m breaking in the new brush.

I’ve definitely added more colors and brands to my palette in recent years. I mostly use Gamblin and am addicted to a few Old Holland colors – light ones in particular. Someone gave me a tube of Old Holland Yellow light as a present and that got me started. I now have about 5 cool and warm whitish paints that I use regularly. Gretna always suggested using light yellow instead of titanium white to keep the color from getting too chalky. Lester Johnson gave the same advice.

JM: Your early paintings were still life paintings and then at some point you began making paintings of other paintings but only from reproductions. Now you’re making paintings of people from photos. Can you talk about the transitions from still life to painting from reproductions of other paintings to painting people from photos?

JN: I have many avenues of investigation, each satisfying different questions and queries.

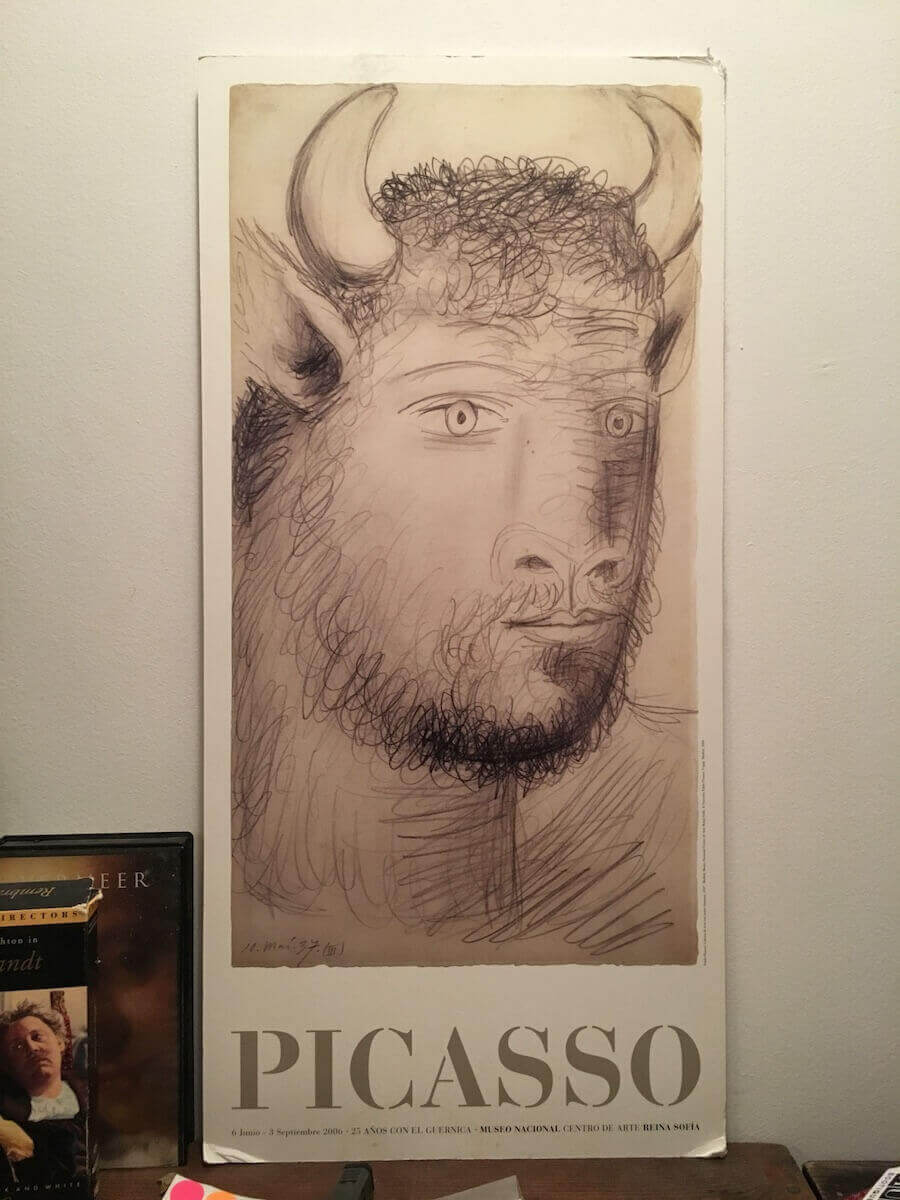

Historically there are many figurative painters who worked from life, photos, and masterworks as well as invented subjects. One of the painters that jump to mind is Cézanne who did still lifes, invented paintings and transcriptions. Courbet, Manet, Picasso, Joan Brown, and Bob Thompson are other painters who worked this way to some extent. One could name many more.

The paintings from photos and reproductions are more about the subject. Since I prefer to work without models present in my studio – this gives me access to people that I can put in my paintings. Having something in front of me operates as my North Star. It acts as a constant that I can refer to as I navigate my paintings.

The still lifes are very much about looking and responding to objects in the world. I only work on them in natural light and it must be the particular light and time of day that triggered the need to make the painting in the first place. The scale is equivalent to the objects when I am at a fixed distance from them. That distance is within my reach.

JM: It seems like you spend a long time on each painting. Can you talk about this quality of a lot of time in your work and why that’s important?

JN: The promise I make to my paintings is that I will bring everything I have to the table; my time, my patience, whatever experience painting and looking for 35 years can bring. What I ask from the painting in return is that it gives me everything it’s got. Looks can be deceiving; a painting that has been designated a “dead horse” can come back to life. My feeling is that no painting is ever dead. It just isn’t finished.

Janice has a solo show scheduled to open on June 22, 2019. The exhibition will be on view in the main gallery through July 14, 2019 at John Davis Gallery located at 362 ½ Warren Street, Hudson, New York 12534. For additional information and to see more of Janice’s work, visit her website at www.janicenowinski.com.