Avital Burg: Textures of Time

Crean and Company and Browse and Darby, London

12 October 3 – 10 November, 2022

Avital Burg’s paintings offer us an acute convergence of attentiveness to the thing seen and the materiality of the paint itself. Overwhelming physicality is employed to describe surprisingly transient subjects such as disposable cups, cardboard packaging, and delicate flowers. Thick paint makes each present in an insistent, even heroic way, while somehow evoking a palpable fragility, reversing our expectations of what heavy impasto can achieve. I first learned of Burg’s compelling paintings from a review of her show at Slag Gallery in Brooklyn in 2015. Since then I’ve followed her work with avid interest. Recently I had the opportunity to correspond with Avital over email about her paintings and process.

Painters’ Table (PT): I was struck by your comments in a video interview when you talked about constructing a “precarious kingdom” in your studio – a world that references history but also acknowledges its own fiction, the impossibility of returning to the past. So, I’d like to start by asking you to talk about your subject matter, how you build that kingdom, conceptually, but also what draws you to the things you paint.

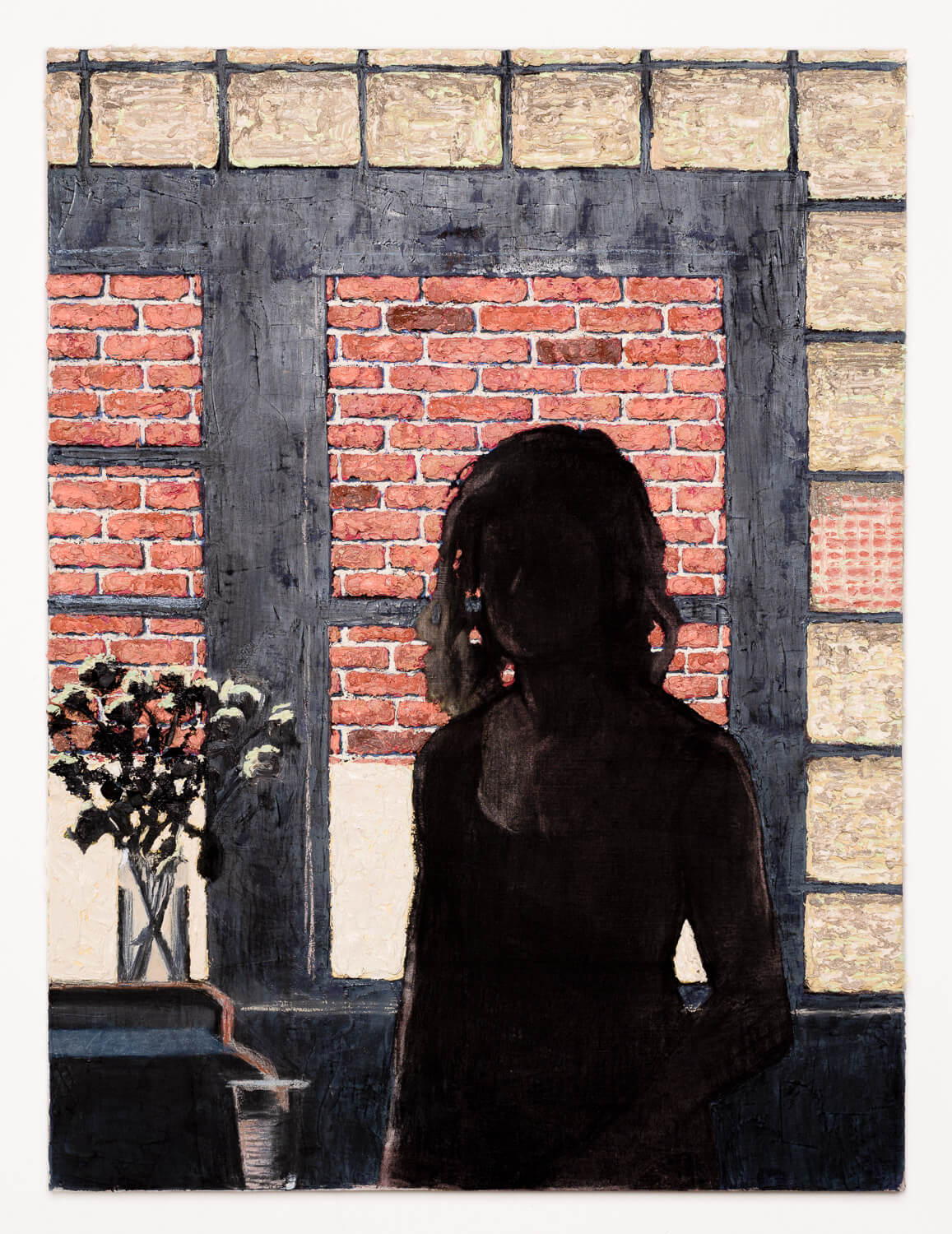

Avital Burg (AB): It is a collection of things that created a kingdom. I did not set out to create it, rather it’s a result of me bringing into the studio different elements which draw my attention when I walk to the studio. They often have a textural quality that is attractive for me as a painter who works with oil. Yet when I took a step back I managed to exit the immediate quality of the singular and view the macro, its entirety, from above. At that moment I noticed that a “kingdom” was starting to emerge and I took it upon myself to now, deliberately, cultivate and build it even more. The different elements in it are anchored in the specific time and place that my studio and I were in, at any given moment. But, often they are related to a larger story, which serves me in tying the personal and internal to the external and global. One example is the brick walls that I’ve been painting in recent years. On the one hand, the pealing brick wall of my studio is my own narrow landscape, on the other hand, the different layers of paint reflect on the different inhabitants and the history of the specific place. And finally, these bricks and walls tell the architectural story of my town, Brooklyn, and even relate to my migratory path from Jerusalem to the US. But it is important for me to point out that all of these different meanings (or layers), come after the fact. First and foremost I was drawn to this wall because of its materiality.

PT: Your paintings imbue fragile, flimsy objects, things typically discarded, with tremendous physical presence. To me it seems this is a product of the convergence of attentiveness to the thing seen and the materiality of the paint itself. How do you think about the painting process?

AB: I look at all of my subjects as excuses to put paint on canvas. Why do I need an excuse? Because history tells us that paint can have divine powers, and I, for one, am captured by this power. My painting education and the way I (and so many other painters) look at art, puts the abstract matter, the paint, before any literal meaning or story. The matter-paint is the end and not the means. The shape-composition or subject matter- is the means. In order to find the shape I look out to the world around me, the immediate surroundings of my neighborhood and studio, and the objects I find there become the reason to put oil paint on the canvas. In other words, I don’t think what to paint but rather to just simply paint. In recent years I made it my main project to experiment with how far I can take this idea of paint as the commanding power. The canvases became thicker with paint and varied with surface activity. I often let the flow of the paint lead my way in composing the paintings. I mix dry paint bits into fresh paint, I paint on top of older paintings of mine and of other people, I add wax, charcoal chunks and pastels into the mix. The objects I choose have to fit into this dynamic: found street flowers are one very good example. They provide the delightful mess and flux that I need for my work. Another set of objects, cardboard boxes for example, are the complete opposite: they are still and quiet, and I can rely on them to constantly be there and fascinate me with their texture, color and shape. On my windowsill I have a china espresso cup; I go back to painting it every season of the year at varying times of the day. It is a tiny anchor of form and color that I can always go back to.

PT: You mention your journey from Jerusalem to the US, could you talk a bit about your backstory? How did you come to be a painter?

AB: Making and seeing art was a huge part of my childhood. The after school art class I went to as a young child was called “Material Class” rather than “Art Class”. Our teacher, who was a pottery artist, gave us a heap of different materials every week and normally went to talk on the phone and smoke in the storage room. These hours in her studio were the most magical: the teacher gave my friends and I what seemed like all the freedom and time in the world. My first encounters with visual art were at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, where I would go on a regular basis with my family and art teachers, from a young age until I graduated high school (I studied there for my high school diploma in arts). The museum’s vast collection is encyclopedic, meaning that the other kids and I were immersed with anything from prehistoric female figurines to traditional Moroccan Jewish wedding garments, European modern painting and contemporary Israeli art. The gallery room I was always most attracted to was a dark room with a display of highly detailed miniature dioramas from a pre-war European collection. These artifacts haven’t been on view for many years, but I still hold fast to their memory, and the enchanting sense of people’s ability to use their artistry in order to catch the spark of reality and put it into objects. Only later, when I went to art school in Jerusalem (Bezalel Academy), did I realize that I actually want to become a painter. Like in so many art schools, there wasn’t much attention, guidance or support for representational painting there and I think that this only strengthened my attraction to walk this path.

PT: You studied at several different art schools in different countries, Israel, the UK and the US. What were those educational experiences like (significant teachers perhaps?) and how have they helped shape your work?

AB: It took me a few years to recognize that the art school of my dreams does not exist. But I think that all of]f the teachers and experiences in the various schools I attended combined together, created the education that I was in need of. In Hatahana School in Tel Aviv I acquired strong foundations in drawing from observation. For the first year there we used only charcoal and drew a model for 8 hours a day. In the New York Studio School I met Stanley Lewis, who became my rabbi, an endless source of inspiration. I think the textures in my paintings are highly inspired by his work. Judy Glantzman was another influential teacher who expanded my horizons with the way she taught and spoke about drawing. When I participated in the student exchange at the Slade in London, I was given a spot in the studio that was once Euan Uglow’s classroom. Even though the school and its philosophy changed a huge deal since Uglow’s days, painting in the same room as him and his students, was enough of an inspirational sojourn, alongside the great teachers who I met there. Among them was Paul Richards, who was an original thinker and wonderful individual to talk to about painting from observation, he also introduced me to two pigments that I’ve been using ever since.

I connect strongly with the painters of London (Celia Paul, Frank Auerbach, R.B Kitaj, Freud…) and this made my stay in London extremely significant.

PT: You’ve lived and worked in New York for a while now (more than a decade? Yes! 11 years), one of the great museum cities in the world. Is there a particular painting you find yourself returning to again and again? Or, perhaps an exhibition that stands out for you, that you returned to many times? If so, why? Has it affected your work?

AB: Whenever I have free time, even if I know I should to go to Chelsea or the Lower East side to see the recent shows, the only place I truly want to go to is the Met. Every time I go there, when I approach the big staircase, I get a physical sensation of joy, it also fills me with gratitude that I am lucky enough to live and work in NYC. Every single time I feel like I’m walking into my dream palace. Two particular areas that I love returning to are the Fayum portraits in the Egyptian wing, and the Balthus nude at the Lehman collection. They continuously demonstrate how paint can achieve the sculptural qualities that I’m in search of.

PT: It’s been a strange couple of years. All (or the majority) of the works in your recent show at Pamela Salisbury were completed during the pandemic. How did the sudden changes brought on by the pandemic affect you and your work? The title of your show, Journal, suggests a day by day approach perhaps?

AB: Yes. The pandemic put into perspective what’s most important, family and health. Yet there is a duality, because what I find myself searching for the most is time to paint. One understands that life is above all, but also, that this life must be constituted upon something, upon some kind of content, and for me that content is painting. It may seem backwards, when the pandemic hit one acknowledged the vitality of health, family etc, but then a secondary acknowledgement comes along and reminds us that even fundamentals need content in order to indeed be fundamental. Life must be backed up by something of importance, by something of true value. The gratitude that comes from living through difficult times may manifest itself in an understanding that this life should be predicated upon something that, at least, I myself see as precious and valuable.

On a more practical note: during the first months of the pandemic, I was locked outside my studio and had to paint from my backyard. I engaged in things I haven’t done for years, like painting cityscape en plain air. Usually I paint flowers that I bring into the studio while they wilt, but during that time I was painting them as they grow in the pots we planted that dreadful spring. Once I was able to return to the studio, every hour there became even more precious than before. With all the loss around us, I think that our newly acquired appreciation of time is huge, and I am making it my point to not forget that.

PT: You mentioned painting the espresso cup again and again. You’ve also consistently painted self-portraits; I note that several are titled as birthday self-portraits. Returning to these subjects periodically (and perhaps others?) suggests an interest in the conscious documentation of time. Could you talk a bit about how you think about time and painting?

AB: Time is hard to talk about. It is elusive, and it is a condition for our existence. It is also abstract, yet we can give it rhythm, a process of de-abstracting time. These reappearing images are my way to put pegs in time and create that rhythm, that pulse. Everyone has an internal rhythm (or internal rhythms) yet they are slightly unknown and can be possibly only discovered over time and within time.

Many of us painters fantasize about an existence of isolation such as Morandi’s or even James Castle’s (right?). But I don’t know if it’s possible to live this way in our time. There is so much distraction, some of it desired (like family life) and some of it isn’t (career demands for example). With never enough time to paint, one has to find the cycles and subjects that keep oneself grounded.

PT: Your work feels very attuned to the world around you, the bricks you paint are specific bricks, the flowers you gather yourself, everyday objects in your studio. There’s a sense of being present in everyday life that feels at odds with the contemporary embrace of the virtual. In the US it seems that, as a culture, we’re detaching from our surroundings. Even during COVID, when so many were home, the focus was virtual: Zoom meetings, the news and social media on phones. How do you see your work (and/or painting in general) in relation to an increasingly virtual culture?

AB: My main project is to load my work with honesty and a grasp of the true and non-virtual existence. Like many painters, I feel that my work is really not fit for viewing on a tiny screen. Paintings are to be seen, they are about the thing itself and not its copy or its pale shadow. This only becomes more apparent in these times. The more the real thing is concealed the more we strive to see it, to discover it. I feel one should rebel against this virtual world, and actually painting is, whether we wish for it or not, a clear rebellion against this current fake reality. Painting today can thrive, not due to the virtual world, but despite it, it can thrive as a clear assault against it. I go to see paintings in the flesh and I demand, by way of my painting methods, that my paintings are seen in the flesh too.

PT: Speaking of the virtual, I recently watched an Instagram live you did with Clare Britt for Ortega y Gasset Projects, where you gave a tour of your studio space. One of the things that’s not as apparent in 2D images of your work is how dynamically sculptural the paintings can get – vastly different surfaces coexist in a single painting. How do you go about resolving such varied paint handling, and what influences the choice of a heavy impasto embedded with charcoal sticks vs thin wash or area of charcoal drawing?

AB: I always gravitated towards paintings with thick paint; such that give you a feeling that you want to eat them, or at least touch them. It took me a while to notice that my surfaces were too flat for my taste, and that the dry paint on my pallet was building up to be way more interesting than my canvases. I started to bring this topography into the paintings themselves, and the eroticism of paint itself allows me to journey down valleys and up hills, it is my most intimate relationship with the canvas.