Kurt Kauper: Women

Almine Rech, New York

January 20 – February 24, 2018

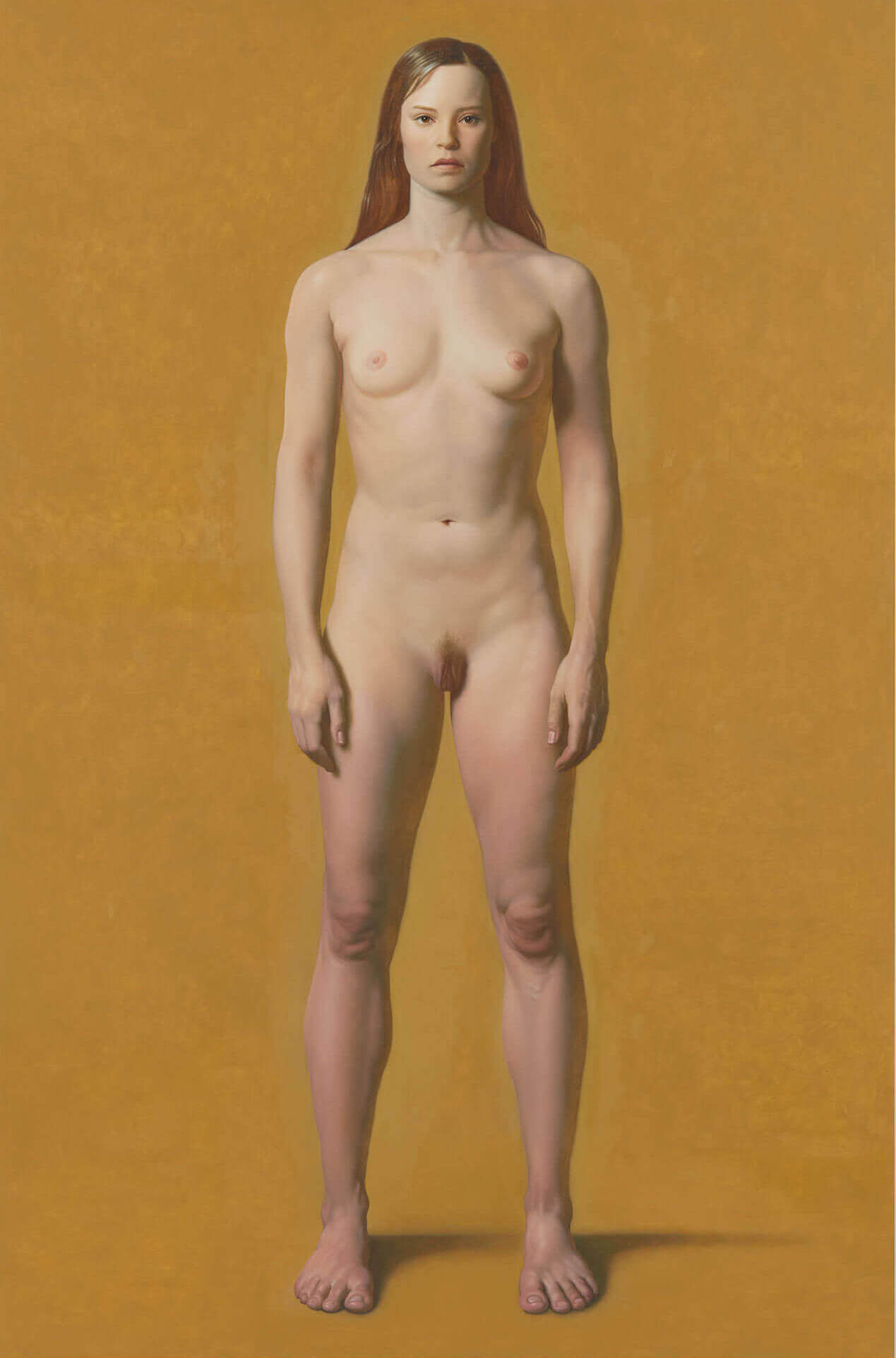

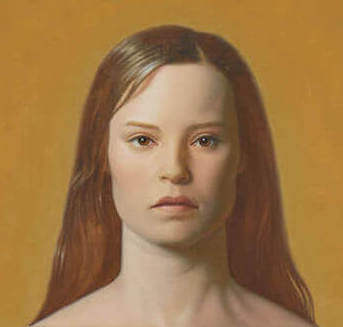

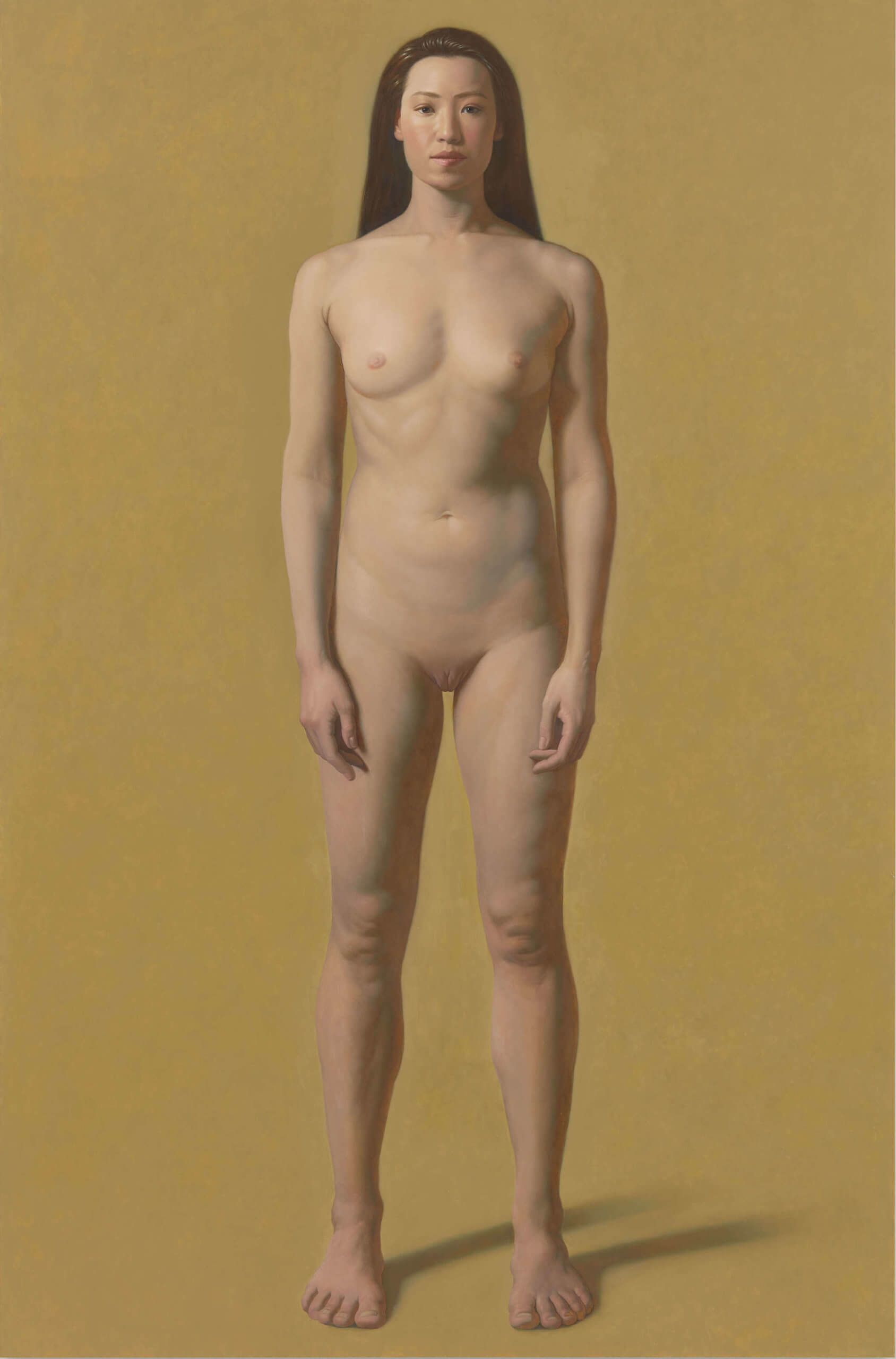

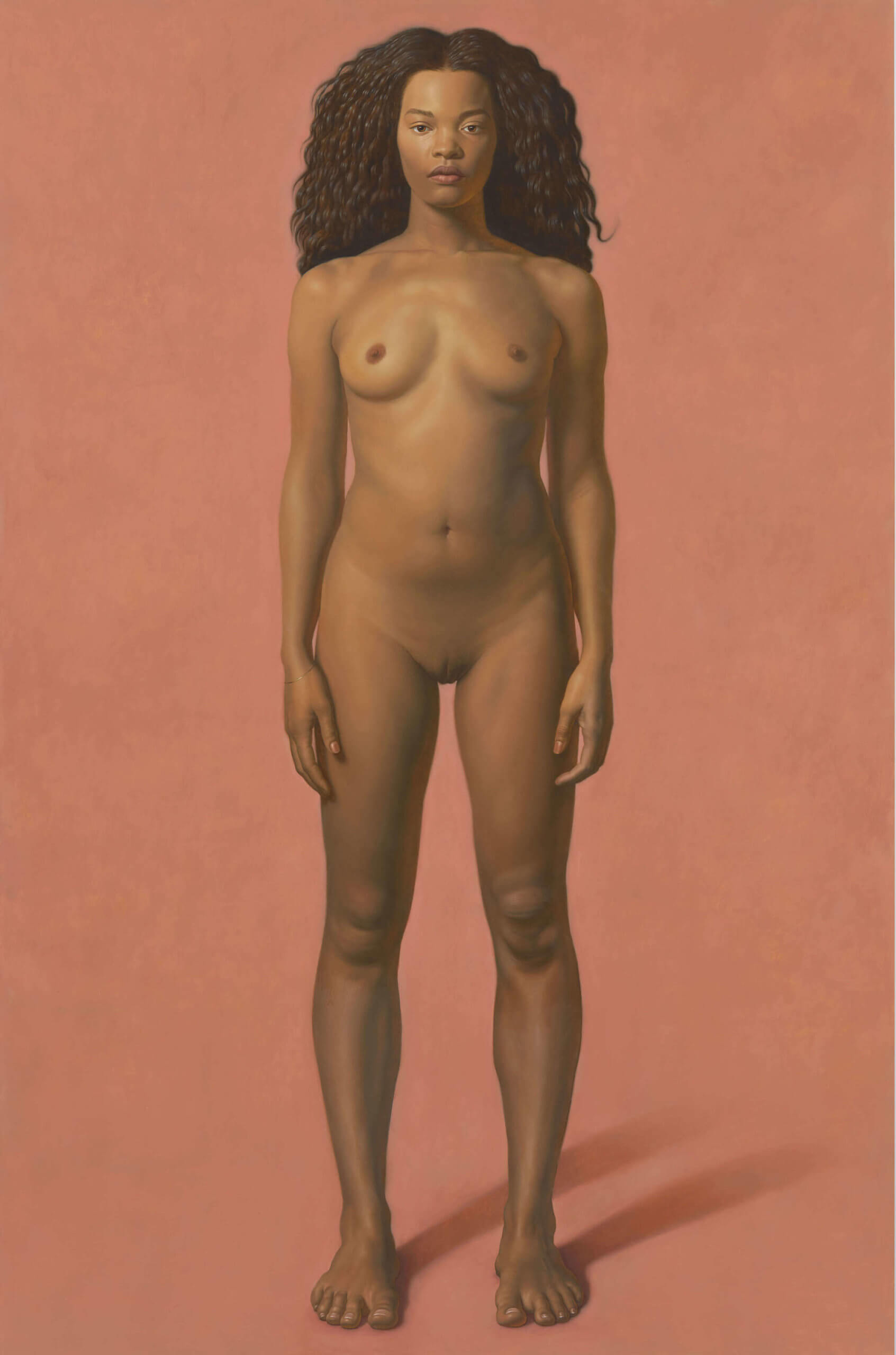

Irony is deactivated in Kurt Kauper’s daring show “Women”. The generic title is witty, but funny paintings of unclothed women by a man, opening the day of the Women’s March in New York City, would overly provoke in the metoo moment. Kauper safely aims instead for “neutrality… by way of deepening, refus[ing the] pure discourse of opposition”. 1 Less individuals than types, the three large standing nudes read as a group, reminding of both the contemporary work of Vanessa Beecroft, and the classic theme of the three graces. With more agency than either example, however, each centrally commands a rectangle that doesn’t contain so much as prepare to launch her. Uneager to please but not unpleasant, they squarely meet our gazes. Kauper’s women are symbols, not unlike presidential portraits – of possible futures rather than historical episodes.

Kauper has also painted the Obamas with a playful familiarity, partly to place himself out of his comfort zone as a painter. 2 But official portrait commissions would demand circumspection and gravitas. While Kehinde Wiley’s showy figures ironically subvert western neoclassical privilege, a quiet earnestness is broached in his Obama portrait. Leafy ornamentation diverts from any uncertainty there, and enhances presidential solidity. Amy Sherald’s formal language recalls African-American aesthetic inclination for the African lexicon that was so spectacularly exploited in Modernism, especially by Picasso. The First Lady presides over her mountainous dress in a pose as unassuming as the design is austere.

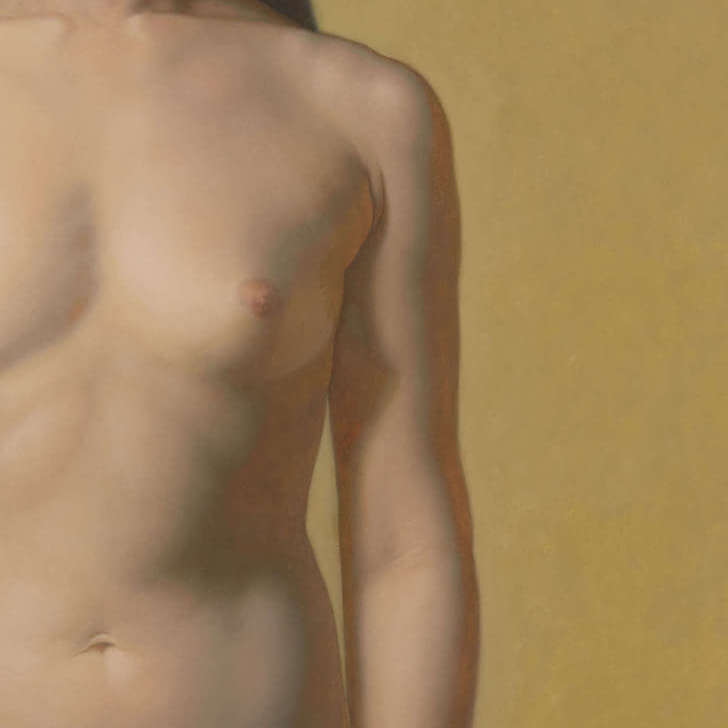

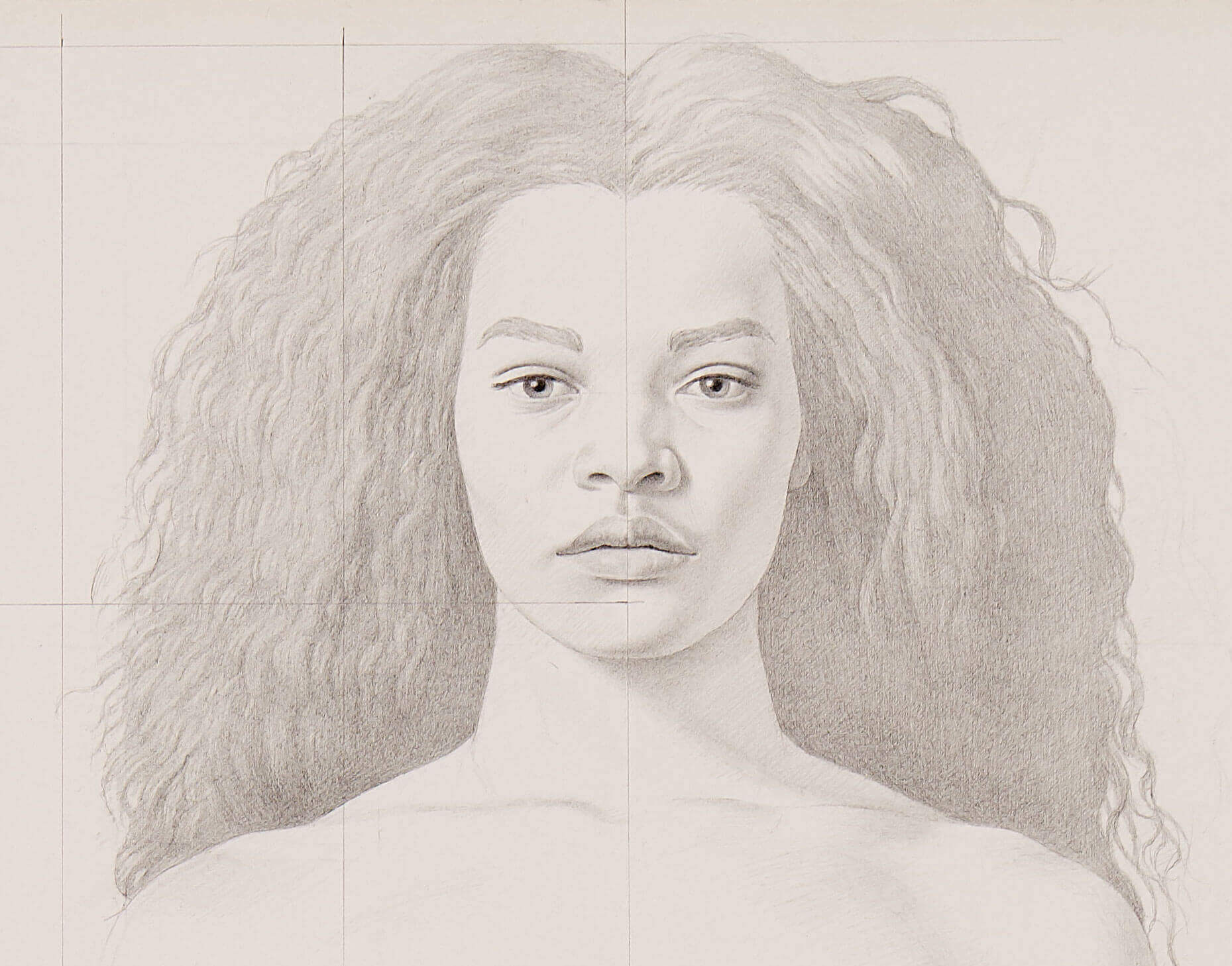

Kauper’s women are likewise both real and ideal – and both naked and nude. Like the work of Christian Schad that Kauper admires, a clear and impartial treatment of parts slows drama so there is no shock. Everything – faces, feet, individually groomed private areas – is evenly offered for calm public consumption, without modesty or shame on the part of either figure or viewer. While straightforward and frontal like Al Leslie’s figures that also play modelling expertise off flatness, there is no dramatic light, no sense of exposure. More like the people of photographer August Sander’s (like Schad, also of the Neue Sachlikeit), unsentimentality presents itself not so much coldly as candidly.

Transparent shadows with subtle reflected light create dimension and render the flesh less humanoid than that of Kauper’s typically arch characters. If soberly clothed these women might descend into the uncanny valley, but weirdness is obviated by the iconic distance and virtuous overtones their nudity proffers. The ideal nude was developed by ancient Greeks in a curiously short time span and promoted by Romans and then via Christian art. It was eventually excommunicated from the western art world during the Cold War while serving the aspirational visions of socialist art. The model of the French Academy thus spread all over the world. While rejecting that academic example largely defined modern art’s mission, it’s worth pondering how odd the original project was – the superimposition of mathematical and architectural ideas onto specifically observed, fit human form. Small wonder most earlier global art forms, notwithstanding trials such as African Ife or Japanese Kamakura sculpture, declined it.

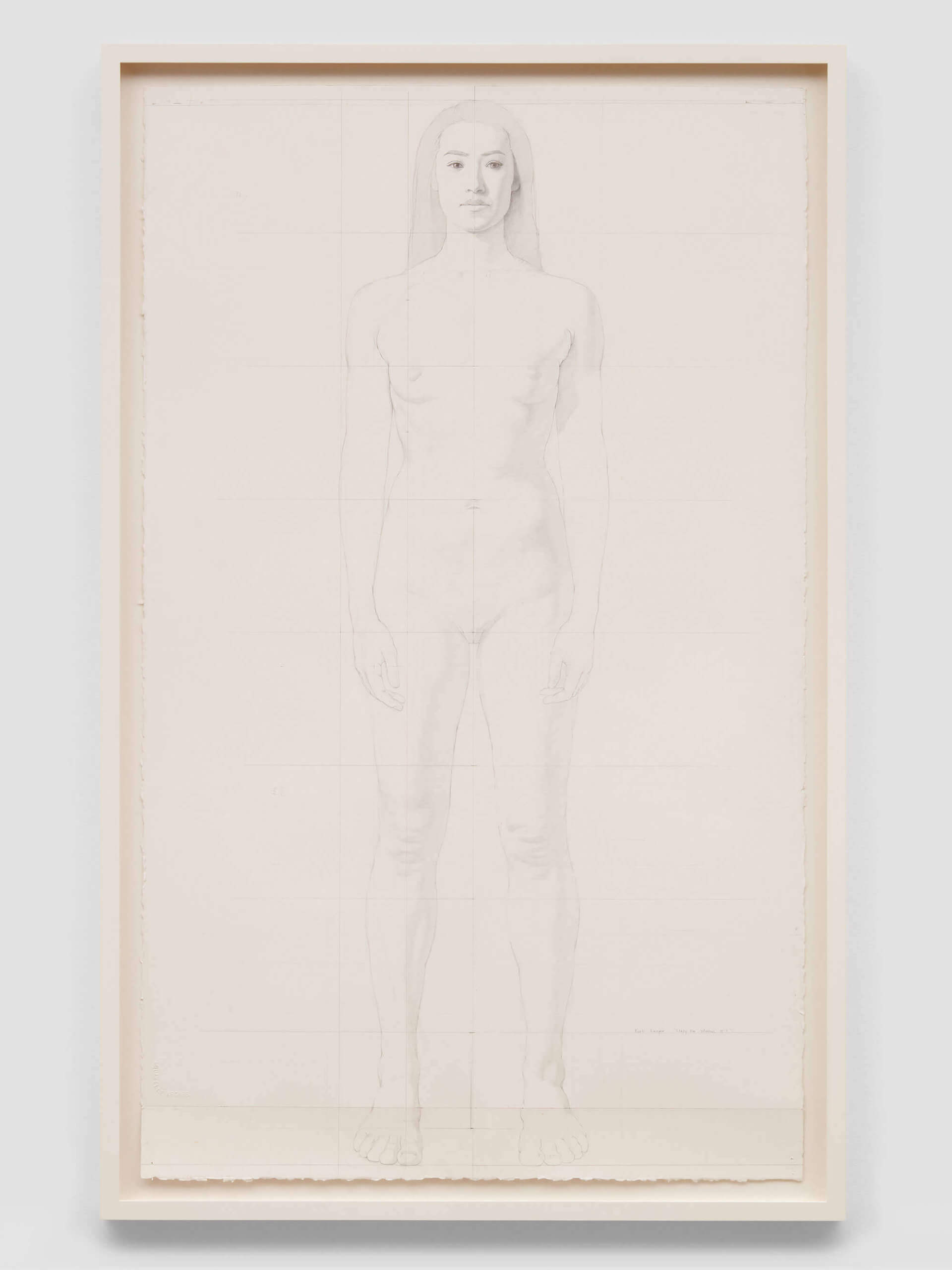

Kauper’s measured drawings make no bones about rational anatomical proportions, and the un-erased grids don’t conceal the academic method of enlarging a study. The quasi-scientific measuring variable so important to “getting the figure right” led to some ugly consequences – phrenological racism and a mechanized vision of human behavior that empowered oppressive political systems. Nazis abused European figure conventions in very poor taste (kitsch), as KKK-confederate monuments exploited it to cement white supremacy. Even today the alt-right uses Michelangelo’s “David” in its propaganda, somehow overlooking the fact that he is a Jewish hero – laughable if it wasn’t alarming.

Unsurprisingly, Kauper avoids the uncomfortable reading of an all-Caucasian trio of women. Further, in rendering one black, one white, and one Asian he seems to uphold the neoclassical figure as potentially if not inherently color blind – not the exclusive domain of “dead white males,” but available without guilt today to living ones painting self-actualizing women.

Kauper also forgoes the elegant contrapposto – a demure pose that invites the “male gaze” and that might have suggested trophies mounted on a wall – for a power stance, arms free to contend, spread feet solidly planted. Michelangelo used the contrapposto in his David not just to show the beauty of the male form, but also to play its balanced relaxation off his scrutinizing face, intently sizing up and planning the defeat of Goliath. There is no such psychological or narrative prospect in Kauper’s neutral women. Situationally aware the way athletes are before a contest, they are “in the moment” to the point of timelessness. This iconic stature gives them a metaphysical air as well, like the figures of Magritte, influenced by pittura metafisica’s mannequins. Like Artemis channeling Eve, they are open and ready for new roles neither the painter nor we can envision.

Notes

1 Roland Barthes, The Neutral – http://www.alminerech.com/exhibitions/4551-kurt-kauper

2 https://www.interviewmagazine.com/art/kurt-kauper-barack-obama