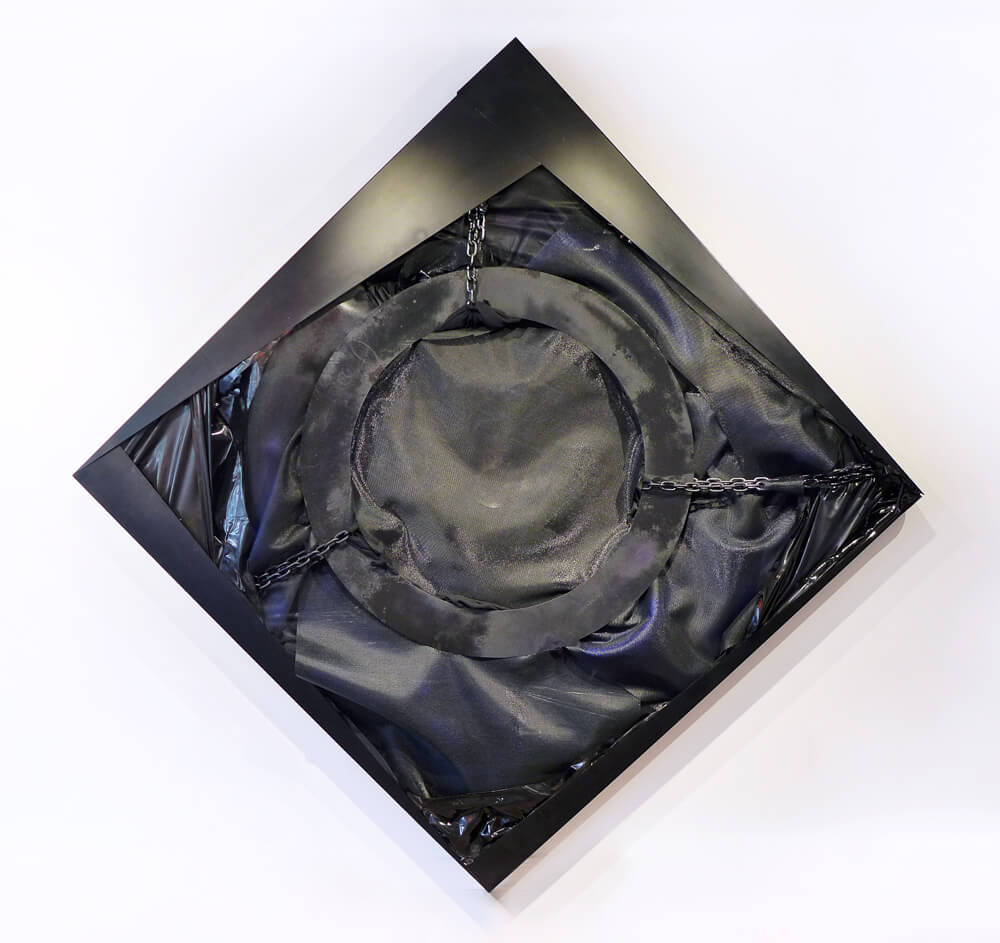

DeShawn Dumas: Future Primitive

Janet Kurnatowski Gallery, Greenpoint

May 31 – July 14, 2013

Like others working at the boundaries of their discipline, DeShawn Dumas often finds inherited categories inapt. His paintings include little paint; he plays with the plane. He prefers materials that possess troubled pasts in addition to their aesthetic qualities. The results are layered. From even a short distance, small print disappears behind screens. Take it as an invitation.

Dumas has a BFA from Indiana University, an MFA from Pratt, and is a year away from earning a Master’s of Science in Critical Theory and Art History at Pratt. I sat down with Dumas at Janet Kurnatowski Gallery in Brooklyn on the heels of his extended solo exhibition.

Cameron Brinitzer (CB): How do you relate to this collection?

DeShawn Dumas (DD): It’s the most cohesive endeavor I’ve ever completed. I’m not a unified individual. I’m made up of disparate interests, ideologies, perspectives. So, even though they are similar in shape, scale, size, and material, they are extremely diverse.

I think one of the most important tasks facing the artist is to investigate the self and see what’s really in there; to reify the hidden corners of your personality. For me, that has meant realizing the diversity within myself. Comprehending this internal difference can create a unity that doesn’t demand harmony, but is complex enough to encapsulate the various aspects of my psyche. That’s the sort of cohesion this exhibition has.

CB: Do you refer to these pieces as paintings, vehicles, or both?

DD: Initially, I referred to them as a form of painting, painting in parentheses. As time went on and I made more, and I thought about my intentions and the historical connections that I was interested in, I came up with the term vehicles. I like vehicles as a term distinct from painting because even though they deal with the principles of painting – line, transparency, opacity, color, shape – their intention is connected to the Vedic tradition, a tradition that I know very little about but seems to know about me.

Sri Yantras are graphic symbols for the universe that were constructed for meditative purposes, to get the individual in touch with the macro and micro. I was initially drawn to them because of their rotation. They have this movement in them that I was captivated by; I would stare at the computer screen for long periods of time, entranced. I thought, Wow, this is better than any sort of visual experience I have when I go to museums.

I also have a regard for manual labor and art’s relationship to the machine, which, in some ways, aligns my work with Russian Constructivists who hailed the death of art and its rebirth as industry. Constructivist art had a utilitarian component; it was a movement that engaged the external, or what lies outside of “fine art.” That’s one historical precedent I’m engaging when I get these aluminum and galvanized-steel frames manufactured. I took some of the frames to an automotive shop to get painted. So, I put painting in parentheses because I’m trying to deemphasize painting. It sounds negative but by deemphasizing it I’m really trying to extend it. To extend something is essentially to go beyond it.

My interest in car culture and my spiritual susceptibilities are present in my work. I’m interested in these as tools that can be used to focus attention. Vehicle seemed like a good word to suggest my intentions.

CB: So they are intended then, in one way or another, to move the viewer?

DD: That’s something that I feel is really important for art. I think people come to art for different reasons. Some come to art for a sort of ritualistic self-representation of their cultured identity. I believe others come to art for an experience, for something they can “use.” I want to give those people something emotional, something seductive, something fraught with tension, something pleasurable. So, yeah, the idea that the viewer is moved or invigorated is paramount for me.

I think art is about energy. It’s not about the didactic, it’s not all about tradition, it’s not about beauty, and it’s not about taste. It’s about energy.

When you stand in front of my works, I want you to have a powerful sensation. I want you to feel a presence, almost as if a person was looking back at you. I don’t want my paintings to be rarefied.

CB: In terms of materials, The Way lists spray paint and automotive paint, Black Balled lists automotive paint, and NutraSweet and The New Jim Crow #1 and #2 list spray paint. There is no paint in The Meek Shall Inherit the Earth, The Unity of the Spectacle, Madonna for Crenshaw, or Danger Donna. Why do you locate yourself in the milieu of painting?

DD: The objects that I’m making are in conversation with painting, those formal principles that have concerned painting. But, most importantly, with painting there is an encounter with the wall and the object on the wall. There’s a sensation that this thing is outside of normal relationships, normal reality; it’s more in your mind. I think that’s why I’m drawn to painting, and I think that’s the ultimate power of painting, or the resilience of painting. Reality can be so mundane.

Materials usually dictate the way art looks. If you go back to the Renaissance, people painted in tempera. When oil paint came out, it had this new ability to convey a vividness and shine that you just couldn’t get with tempera. I believe vinyl and fiberglass screens allow for a new form of expression that you can’t get with oil paint or acrylic.

CB: With whom are you in dialogue?

DD: One movement that I am always dealing or struggling with is American Conceptual Art. I’m always trying to get information into my work. Not didactic information. The information in my work is intransitive, like an intransitive verb – an action that has no object. I’m not telling you where to take this information, but I am telling you that I’m concerned with these ideas of origins, history, eschatology, theology, industry.

The other two movements that I’m always coming back to are Minimalism and Pop Art. Minimalism engaged with industry, getting things fabricated, taking the artist’s hand out of the production of art, while still making reference to the institution or structure that made the work possible. From Pop Art, I draw ideas about the profane, the graphic, and the magic, grace, and glamour of the commodity. These are things my work engages.

CB: Are there any artists with whom you identify?

DD: Sam Gilliam is somebody who changed my concept of art. I saw a retrospective of his at the Corcoran in twenty-o-six and he was doing these draped fabrics. These draped, tie-die fabrics hovered over a room with this weightless quality; and then you had the shadows these objects created. They had a theatricality to them that I appreciated. Steve Parrino and David Hammons as well.

CB: When did you make the paintings/vehicles for your exhibition, Future Primitive?

DD: I made The Meek Shall Inherit the Earth in January of twenty-thirteen. I made The Way in May of twenty-thirteen. I made The Unity of the Spectacle mid-March. I made Black Balled in May as well.

They diverged immensely from the work that I was doing last March, last January, and last May. My turning point came in the summer of twenty-twelve, when I decided to make a piece that I didn’t like. I said, I’m gonna make a piece that’s not me, and that was actually the piece that was exhibited in Chelsea last December. The piece was green; therefore, I didn’t like it. I had never used green in any of my work. But it was an interesting painting. Because I separated myself from it at the very beginning, I was able to go beyond myself.

That piece did not have the space that these have, but it did approach the overlaid quality these have, where geometric qualities exist alongside the organic or bodily qualities of the drape and fold. That piece brought me here.

CB: Can you describe the process of making a piece?

DD: It’s usually a lot of carrying shit. You know, getting coffee grinds from Starbucks, going to the grocery store to get flour and sugar, going to the hardware store to get nails and staples, or wood and steel supports, or chains. Then, I’ll go into the city to get vinyl off Canal Street and up to the fashion district to get fabric. I always buy too much and never get what I need, so there’s always repetition.

I usually start all of that around two [PM] and I’ll make the final migration to my studio around eight or nine [PM]. I like working off hours, when it’s not nine-to-five. During the day, I feel like there are so many other consciousnesses around, awake, hustling, bustling, that I can’t get beyond that energy. I like working when people are asleep, or in leisure. So I work from, like, ten [PM] to six or eight [AM].

Since these are really structured paintings, a certain amount of work has to be completed before another aspect of the painting can be started. I’ll stretch the canvas over the frame, which will ultimately be the substratum of the piece, and things will float above it. I usually place a reflective surface over that, which replicates the white of the gesso.

From there, it just depends. It’s a lot of adjustment and readjusting things until they click. It’s a lot of trial and error, actually. I’m hoping that as I move forward I’ll be able to lessen my mistakes, my do-overs, my trips to the store.

CB: How flexible are you when you’re working, as regards whatever you have prefigured? Do you try to stick to your original idea for a piece?

DD: I let the mistakes or the chance occurrences that happen in the production of my art guide the production of my art. Paintings don’t work when I stick to my intentions. It’s always letting go, giving up, losing, failing. There is a lot of failure in all of these. But, failure usually creates something and the destruction of my idea usually creates something else.

I’ve painted over and destroyed a lot of paintings. I never really feel close to anything, especially in my work. It’s easy for me to let go now that I understand there’s nothing to hold on to.

CB: How do the four smaller pieces fit into the show?

DD: They were made with less forethought and less planning. Because they’re smaller, I was able to make something with less detail, so they are very direct. But they’re connected to what I’m doing with the larger pieces; in fact, they might be a better example of what I’m attempting to do, as far as bringing different materials and different histories into my work.

For instance, NutraSweet and The New Jim Crow #1 and #2 are ready-made panels that I doused in packets of NutraSweet, burned with a torch, and then wrapped in organza fabric, which has these lines. This lined pattern has been a mainstay for modernism, whether it be Frank Stella, Morris Louis, or any number of modernist painters. But I wanted to point out an evocation of bars with my title, The New Jim Crow.

With the privatization of prisons, starting in the 1980s, incarceration became an avenue to make profits. Jail has become a place where black bodies that aren’t going to be integrated into the system can still be used to make money. Aspartame was approved by the FDA in 1981. It had been banned for two decades because of the harm it caused rats. It has been linked to high cancer and obesity rates, and it’s used in a lot of diet products.

By naming it NutraSweet and The New Jim Crow I’m trying to point to the idea that this overprocessing of our food is essentially a way to make money, or to open up a new space or market that can be capitalized; and, I’m aligning that with the idea that the black body has always been segregated from the American social and finds in the prison complex a space where it can still be segregated but can also be profitable.

CB: How do you think living in New York City has affected your art?

DD: I realized that layers are a way to create space while sitting in a Starbucks in Washington Heights, near my home at the time. I was sitting in Starbucks, looking out the window. They had their transparent logo on the glass, so I was seeing through the logo, and then I was seeing people walk by me, and then I would see people walk by them going the other direction; then I could see the street, and then I would see other stuff going on. I don’t think I would have learned the intensity that overlapping gives without coming to New York.

CB: Would you characterize this as a pivotal period in your own artistic development?

DD: I wouldn’t say this is a climax because it’s lifelong. For me, it’s about trying to understand the stories I tell myself to rationalize what I do, and the stories that society tells itself to rationalize what it does or has done. My work is always going to be a dual critique: of myself first, and whatever surrounds me second. It’s this idea of trying to observe myself observing; and, while I’m doing this second degree observation, knowing that I am in the milieu of whatever I might be critiquing. There is nothing that I critique that I am not also a part of; that I do not participate in.

CB: Do you consider yourself a professional artist?

DD: What does it mean to be a professional? If it means to make a living off what you do, then no, I’m not a professional. But, if you consider a professional as someone with a certain attitude, a certain aptitude – I think what I’m doing will have to be considered historically at a certain point. I’m deeply engaged in the system or tradition of painting, but I’m recoding it for the 21st century.