Zachary Keeting: Recent Paintings

New Haven, Connecticut

September 6 – October 5, 2013

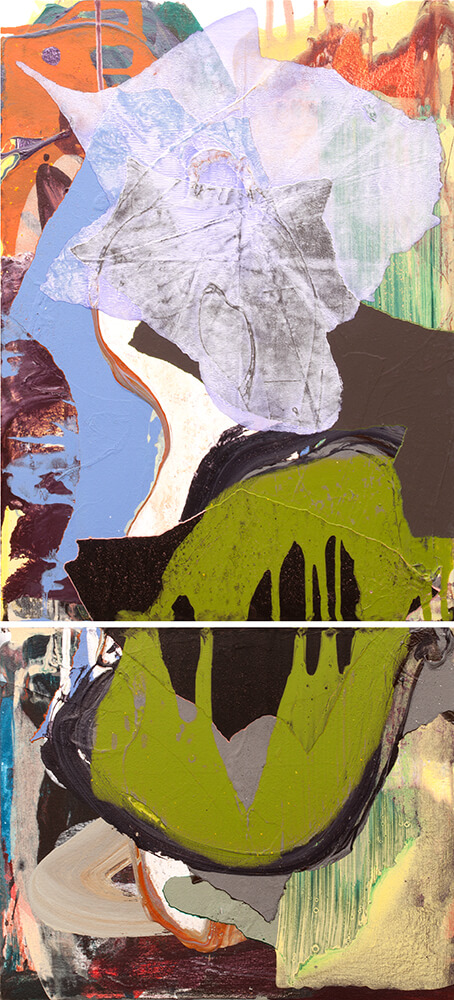

I recently spoke with painter Zachary Keeting over email as he was preparing to install his exhibition at Giampietro Gallery. We discussed his new paintings, in which energetic process and subtle observation collide, generating dynamic, abstract worlds. The resulting works evoke the beauty, emotion, order, and mayhem that lie just below the surface of everyday experience.

—Brett Baker

Painters’ Table (PT): Visual complexity seems to be a constant your work. Over time, however, it appears the main source of that complexity has changed from the interplay of more discrete, carefully invented forms to forms defined through an increasingly physical painting process.

Zachary Keeting (ZK): I would say a desire for complexity has been a constant. I see the world as an incredibly complex place, a baffling / gorgeous / brutal environment. Over the years, I’ve increasingly attempted to emulate that richness in the pictures, to participate in it.

When I was younger, I was completely overwhelmed by the variables of painting. I adored Modernism for its bravery, but I was only able to take it on bit-by-bit, incrementally. I took touch right out of the equation. All the surfaces were consistent, so were the edges. Everything was opaque all the time. My starting point was nutty, idiosyncratic design.

I was trying to get a lot into each piece – nervousness, claustrophobia, longing – trying to depict disparate, overlapping ideas simultaneously via razor-sharp accuracy and jigsaw logic. I’m proud of this stuff, but I can’t imagine ever making work like this again. The past ten years have been a deliberate attempt to change as a person. Become more porous. Let in greater portions of the world, its flux and struggle, and have the paintings join me for the ride.

PT: In your most recent work, the fluid addition and subtraction of material seems to have reached a fever-pitch. The collateral damage that happens as forms collide with one another seems to play a large role in determining the final image.

ZK: I’m still careful laying out shapes / orchestrating compositions, but the edges and interiors have changed completely. I’m still masking off areas: before to contain color clarity, now to contain mayhem. I’m cordoning off zones to differentiate temperament. I’m much more forgiving of slippage. It has to occur at this point. The pressure is completely different too. I’m punching, scraping, shaking, blotting, pouring, staining. It is, however, the same damn acrylic.

I want crosscurrents, contradiction, anatomical corners, and multi-part harmony. Something limber.

PT: Are these paintings the sum of destructions?

ZK: Strangely enough, and this may sound incredibly corny, but I still think of the images symbolically. I’ve always attempted to sort through personal experience / human interactions / conversations, by retreating to my room and moving paint around. The picture above (from 2000) is definitely an attempt at orchestrating thoughts and occurrences, mostly inchoate desire, into a satisfying picture. The more recent picture (above, from 2013) may not have the nameable components, but it’s broken up in very particular ways, and I hope the resulting image breathes in the same air you and I share. Is it destructive? There is a lot of blotting and erasure going on, a lot of boundaries being transgressed. The kind of thinking up top – blues and pinks partially wiped away – does pour down and contaminate the base. I hope it feels true.

PT: A lot of gestural abstraction relates closely to landscape but your paintings evoke human experiences – intense battles and struggles, either violent or passionate; interactions occurring so close together that only part of what is happening can be perceived.

ZK: I wonder if it’s the gestural linear elements that keep these pictures locked in a human scale. I do have a size limit. The biggest paintings I’ve been making recently are 54 x 54 inches. I sometimes amp it up to 66 x 54 inches if I’m feeling particularly brawny, but I’m not that strong and I need to manhandle them.

PT: This size picture (54 x 54) certainly makes the most of the arm-scale gesture which relates to the body. But, for me, the human scale of the paintings has more to do with the fact that in many of them, massive shapes dominate large areas of the paintings and push smaller, more complex areas of painterly incident out toward the edges. The paintings have very active foreground spaces – and subtly shifting depths of field within these spaces. The resulting image feels very present – the action is right there in front of you.

ZK: I strategize on an easel, figure out where things needs to go, build up wet grounds, then lay the paintings down flat. Stoop to conquer as Helen Frankenthaler used to say. I table the canvases, rock them back and forth like a marble maze.

All of the recent gestural marks were made in an observational manner. I’ve been sharing a studio with Christopher Joy, and his sculptures are all over the place. They give me a lot to look at. They’re embedded with hundreds of tiny decisions, lots of anatomical curves, naturalistic anomalies. They’re rich and gnarly. I’ve been using them as still-life objects, things on which to rest my eyes while my hand cuts loose.

PT: The gestures in your paintings do feel like they are on the cusp of description – they describe but don’t name. There is a lot of drawing in these pictures; the linear elements aren’t just linear, they are true contours, moving both in-and-out and side-to-side in particular ways. There ends up being a kind of illusionism without the illusion.

ZK: I’ve made many paintings over the years that were completely invented. From start to finish I looked at the canvas. Some were suggestive of landscape, others hinted at figuration, but everything came straight from my imagination. I remember striving for complexity – for life-like complications – by adding facets, adding colors, adding decisions.

But I’d have to say, keeping your eyes on something else while working through a composition kicks up the complexity quick. Or keeping your eyes closed… have you seen those amazing de Kooning drawings?

PT: Yes, his “eyes closed” drawings are really interesting to consider, because in those works he retains the ability to convey spatial information through his mastery of materials. Even though his sight is literally closed off, the variation of pressure he applies to the charcoal and the relative length of his gestures creates a believable space.

ZK: I let my eyes wander to things inside, things outside. I bring as much specificity as possible to these planar forms and their placement. They’re my springboards. I want them to be just as animalistic as the gestures. They receive spills, are troweled, are heavily blotted. These zones are the wet grounds into, and around which, the action takes place. I make several moves a day – sometimes scattered across separate canvases, sometimes all on one. The pictures are built up and torn down incrementally.

For a few years there, I worked exclusively on paper, struggling to incorporate speed into the pictures. In 2010, I started crumpling up tin foil and placing it around the studio. It held a shape, had dazzling hypnotic surfaces if I dropped it in a sunbeam, and was far too complex to draw accurately with a loaded, soppy brush.

There wasn’t any content in the foil for me, it was simply a daydream prompt, an eye holder. The piece below was partially triggered by this daydreaming. I wasn’t really after naturalistic depiction, but physical release. Bodily freedom.

PT: De Kooning said something similar about the blind drawings, that he had images in his head but closing his eyes allowed for more surprising results – the goal was more freedom.

ZK: I set up fearful situations for myself. I carefully work on large areas of flat pristine color, make sure the shapes and edges are impeccable, build things I’m really attached to, the kind of stuff I don’t want to kill… and then, with knots in my chest and with great speed, I bring observational drawing into the mix. Fear of ruin is a motivational force. These set-ups, more often than not, are only partially successful. Only small sections of each calligraphic move possesses any vitality. I conceal those parts that seem routine, cowardly, stylish. So, much of the overlapping is erasure.

PT: A grisaille palette seems to be creeping in in the most recent work, sometimes with some residual color. What prompted the change in palette?

ZK: It was a difficult summer, and things felt grey. Yanking color out of the equation is something I rarely attempt. It seemed risky.

PT: Through your video blog, Gorky’s Granddaughter, you’ve visited the studios of many artists. How has that kind of intense dialogue with so many artists affected your painting? Do you see GG as part of your studio practice, or is it a separate endeavor?

ZK: They’re superimposed like the brushstrokes. They bleed and contaminate one another beautifully. If I think about it… and I try not to… Gorky’s Granddaughter is an insanely extroverted project. I’ve never done anything like it in my life. Making paintings is completely private. It’s whiplash moving from one to the other.

This gets back to your original question of visual complexity. When visiting studios I never know what to expect. Sure I’ve seen jpegs online, but artists are always presenting us with new stuff, experiments. And what are the appropriate words to use? It’s easy to get all turned around. There’s a reaching out, an opening up, a lot of listening. I hadn’t anticipated this when we started, but each artist changes me slightly. It’s been incredibly nourishing. I try to hold all of this complexity in my head, and in my heart.

These paintings are – in some ways – depictions of that nourishing jumble, the ricochet of my mind, what happens after the talking.