Margaret McCann interviews painter Megan Marlatt on the occasion of the recent exhibition Megan Marlatt: Substitutions for a Game Never Played at The Visual Arts Center of Richmond, Virginia.

Margaret McCann (PT): What does the title of your recent show, “Substitutions for a Game Never Played,” at The Visual Arts Center of Richmond VA, reveal about your sense of play in art-making? Jung said, “… play [belongs] to the child, [appearing] inconsistent with the principle of serious work. But without this playing with fantasy no creative work has ever yet come to birth.”

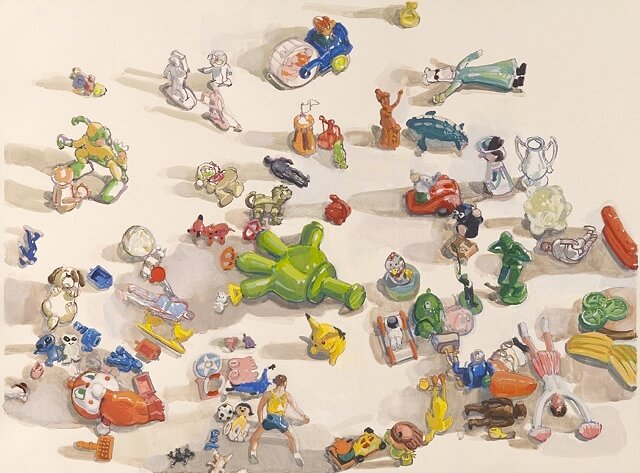

Megan Merlatt (MM): Jung is correct, and as the oeuvre of my toy work grew, so did my empathy toward child’s play and similarities between that world and the artist’s. I became interested in the “anima” in “animation”…what makes dead matter come alive, how do both the child and the artist imbue life into seemingly inanimate objects?

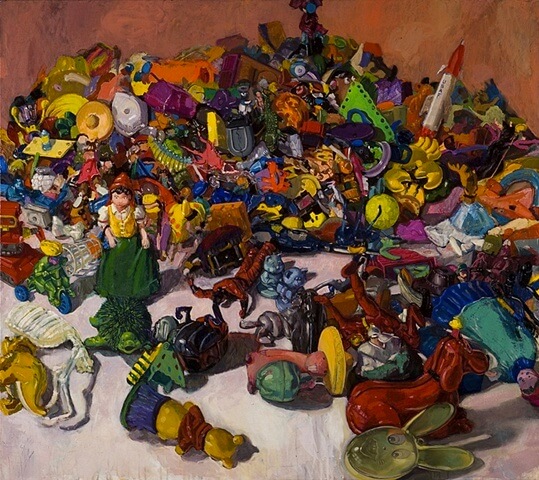

PT: Large piles of toys gathering dust don’t speak well of our consumerist culture, and my inner hoarder feels slightly ashamed looking at them, but then they also reflect Baudelaire’s statement that “Is not the whole of life to be found [in a great toyshop] in miniature – and far more highly colored, sparkling and polished than real life?” Are the paintings also about pure pleasure?

MM: Yes, and I hope viewers have the same conflicting feelings – both damned and seduced by our plastic consumption. Admittedly, my first response to the toys was that of a visual artist; they were colorful and their forms were smartly engineered and enjoyable to paint and draw. But I’ve always been interested in the human condition and how social issues affect art making, so I couldn’t avoid that most of this stuff was wasteful junk. The more I collected and piled the toys up, the more the paintings began to speak to me of a mass, cultural vertigo…a dizziness of too much stuff, too much stimulation, too much information, too much plastic. Mass consumerism doesn’t just produce masses of junk, it can rob us of our sense of preciousness.

Yet I’m not above being seduced myself, and ironically, plastic can evoke a sense of preciousness, in that inevitably I’d pull from the wreckage a toy from my childhood, or one so well crafted one couldn’t help designating it ‘special’. As I’d paint these individually, as portraits, they turned out to be the ones through which I began to feel the meaning of child’s play in the artist’s studio.

PT: How important is ‘degree of difficulty’ for you? Paintings like “Venetian Red Riding Hood” show mastery – skillful but non-fussy drawing, clever manipulation of light, beautiful color, and an expressive handling of paint. Their ambition (50+ figures) reminds me of the technical virtuosity academic history painting placed on multi-figure compositions. Can toys be people, too?

MM: Well, I have been painting for a long time, and I’m aging, and life is short – so I feel my efforts are worthy of ambitious instead of half-hearted ones. My intention involves blurring the lines between genres, so that still lifes can read as landscapes, portraits, history painting, etc. But as gravity pulls the toy piles downward over time, and as the toys appear to move during close observation, jiggling in the corners of my eyes as I turned to find the right color on my palette, the blurring continues; I wind up painting ‘un-still lifes’. Toys are so ‘loaded’ culturally and emotionally they can substitute for many things.

PT: You create great color harmonies, despite Roland Barthes’ lamentation that “toys are made of a graceless material… plastic…has an appearance at once gross and hygienic; it destroys all the pleasure, the sweetness, the humanity of touch.“ Does your painting plastic objects with plastic paint (acrylic) say something about the alchemical power of painting? Does the bright color of acrylic paint relate to the unnatural color of the toys better than oils?

MM: Absolutely. My first toy paintings from 2004 were in oil, because I hated acrylic paint. It’s crappy stuff that’s difficult to mold into illusionistic space – no flow, just sticks to the canvas. I wanted to kill the guy who invented it until I realized how perfect it was for the material realism I’m after: In the same way that Van Gogh’s paint in “The Potato Eaters” is as dirty as the dirt on the potatoes, or that Wayne Thiebaud’s paint in his cake paintings is laid on like thick icing, my paint needed to flatten out like a big plastic Tonka truck that melted on a heater, so the motif and the material became one. Nothing paints plastic better than plastic; I couldn’t get their toxic colors with oils. I begin the paintings in acrylic and finish them in oils in an alkyd medium.

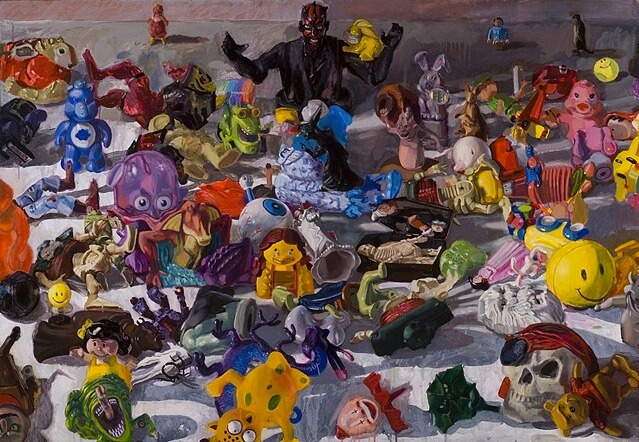

PT: The seductive, cool, blue light of “Dark Eros and the Moonramp Walkers” helps conjure up a vision of the magical landscapes we can recall making with dolls and toys as children. But its realism appeals to adult awareness of our obsession with war games.

MM: I always loved the Rocky and Bullwinkle Show for that reason…those politically charged jokes for adults (if they were paying attention) that harmlessly flew over the heads of the kids enjoying the cartoons. A painter friend of mine interpreted my paintings as an amassing of evildoers who want to destroy my life, and heroes who want to save it – so a personal rather than global war. The paintings become very different for me when the color is limited. The toys are more somber, their structures highlighted as a result of the lack of color. The Dark Eros in this particular painting refers to that strange tiny toy in the bottom left corner of the pile. He’s got a silver suit on like a space man, but he also has wings and Cupid’s bow and arrow…so what he’s supposed to be?

I like that ambivalence of toys, which is only made stronger by the fact that I haven’t watched TV in twenty years. So I don’t know the ‘official’ narrative behind many of the toys I paint. I once picked up a yellow character biting his nails while sweating profusely, and thought, “Wow, this toy is having an anxiety attack!” – which I liked, so I painted its portrait. I only found out 3 months later that it was SpongeBob Squarepants, and 2 years later finally saw an episode on a friend’s TV set.

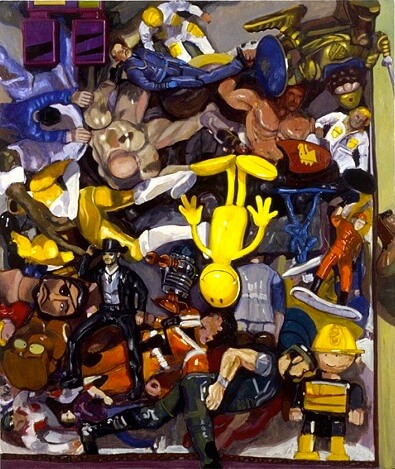

PT: We seem to be living in an un-heroic age, when traditional ideals of masculine action a la The Great Man Theory suffer a dwindling arena outside sports and warfare. Does your painting’s title “Men” reflect that?

MM: Painting dolls, issues of gender and feminism stand out – not a bad thing; I enjoy being a part of both. But while a toy can be many things, a doll’s role is limited in play with her. In setting up a mass of ‘male dolls’ in “Men,” I realized they had a far wider variation of body type and ‘professional’ associations than their female counterparts, either baby dolls for young girls to play “Mommy” with, or skinny fashion models for young girls to dress up. The male variety included muscle men, chubby construction workers, cowboys, rubbery neon smileys and even dictator types.

PT: The verisimilitude of the weighty toy piles dominates from a distance, but close up the active paint textures contradict it – realism gives way to abstraction, and solidity to atmosphere. I can’t help being reminded, in the face of so much toy-waste, of Marx and Engels’ view that capitalism makes “all that is solid melts into air”. The anarchist Emma Goldman said, “Only when human sorrows are turned into a toy with glaring colors will people [be interested] …the people are a very fickly baby that must have new toys everyday.” Do you at least hope that after people see your paintings, they might consume less?

MM: Wonderful quotes! Someone once said of my paintings that the child who these plastic toys are made for would become bored with them very quickly, yet the toys will barely decay, and will be around long after the child is grown and dead.

PT: In places, drips frankly assert modernist flatness. And mark, texture, and color dramatically interplay in rhythmic logic, creating visual gestalts that read abstractly.

MM: I love both realism and abstraction, and for paint to behave like paint. Achieving illusionism doesn’t mean you have to be tight. The painting is many different paintings, depending on where you stand in relation to it. It can be a theatre, in that there is an audience and actors on the stage. But where the audience sits still and the performers move on stage, in a painting the actors sit still on the painting’s stage, and the audience moves in and out of it. From across the room it’s a different painting than from 6 inches away, so the painting changes as one walks towards it, and I like to provide my audience with a different act at each stage of their approach. So, yes, some things that may appear realistic from afar morph into abstraction as they come near – Chuck Close is a master at this, as are Goya and Turner.

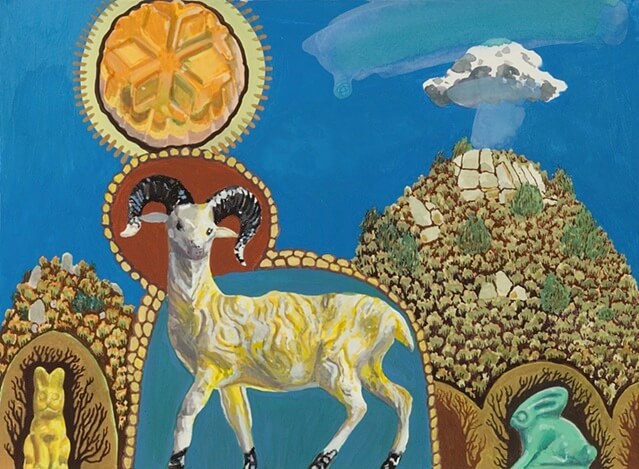

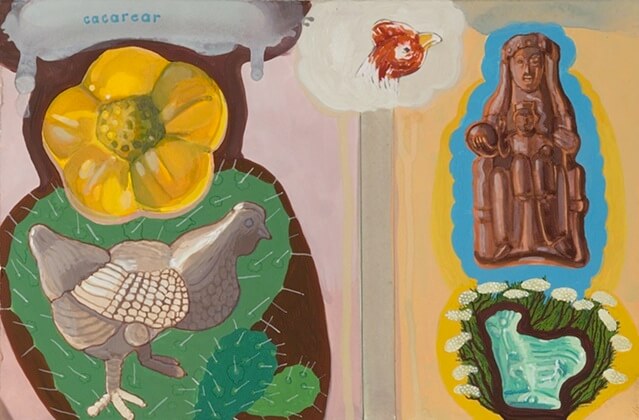

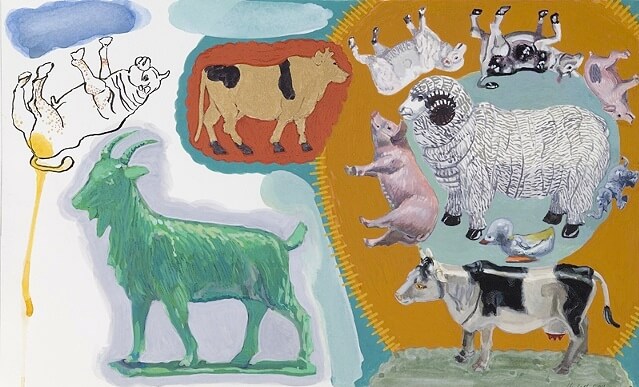

PT: Your smaller gouache works don’t form space so much as revel around the picture plane, engaging in lyrical, taxonomic pleasure. They feel more innocent, like the lighter side of fairy tales before a rude awakening.

MM: Working from observation, sometimes I really get tired of gravity. I mean really, does everything always have to be tied to that damn plane – that tabletop? During the 90’s, my work was influenced by both scientific illustrations and manuscript illuminations. Their visual languages, instructional charts and diagrams, shared a common purpose, since both science and religion try to explain the Universe. The new gouaches are a partial return to that work involving my own inexplicable ‘explanations’ of the universe. The curator of “Substitutes…” saw the small toys in these pictures, wrapped in individual colored forms, like small toys enclosed in a hand. This was insightful, as that is how I painted them, held in my hand, not relying on gravity to stand up. So maybe they do convey a more child-like experience.

PT: How do you know when a painting is finished?

MM: It has to feel alive. In choosing special toys from my piles and setting them aside for portraits, I began to understand the parallels between how a child animates a toy and how an artist animates a painting. Inspired by Philip Guston’s view of Rembrandt’s self portraits – in them “the plane of art is removed. It is not a painting, but a real person – a substitute, a golem…” I endeavored to paint my puppets the way he saw the Rembrandts. The toys ‘sat’ for me and I painted them as if they were real; if I did not paint them “right”, they would be static, flat and illustrative. Only after many hours, layers, mistakes and corrections would they come alive…and then they were finished.

MM: If you have set up a good situation in your life to make art, then creating the work is probably 90% of success. The rest is a song and dance we have far less control over…. recognition, success, sales, fame. All I can really control is whether or not I am going to have a quality life that allows me to do the thing I love the most. I love my studio and I notice that when people visit it, they love it too. But the isolation of a small town can get a little too much; there are probably more people in one high-rise Brooklyn apartment building than here, and making all this work without anyone seeing it can feel like singing into a paper bag. So I’ll take the train to DC for a day or New York for the weekend, go to artist residencies, travel, and regularly show.

I like to think my world isn’t defined by any geographic boundaries – and really, when you are painting, you’re “up there” anyways. And social media, websites and blogs keep me in touch with artists and art events, which helps break my isolation, and fosters networking and participation in an art community of interesting people who all like to share their interests. However, it’s a big-city assumption that there is nothing to do in a small town, and there can be plenty of isolation in Midtown Manhattan. There are plenty of demands on my time that can keep me from studio bliss.

PT: You always have your students read Baudrillard’s “Simulacra and Simulation” – how would that influence their understanding of your paintings?

MM: I utilize observation as a diving board into a pool of all sorts of painting possibilities that toy with realism. My favorite part of the book is when he talks about how Disneyland exists to make us think everything outside of Disneyland is real – so it makes them question reality. Like Robin Williams said, “Reality – what a concept!”