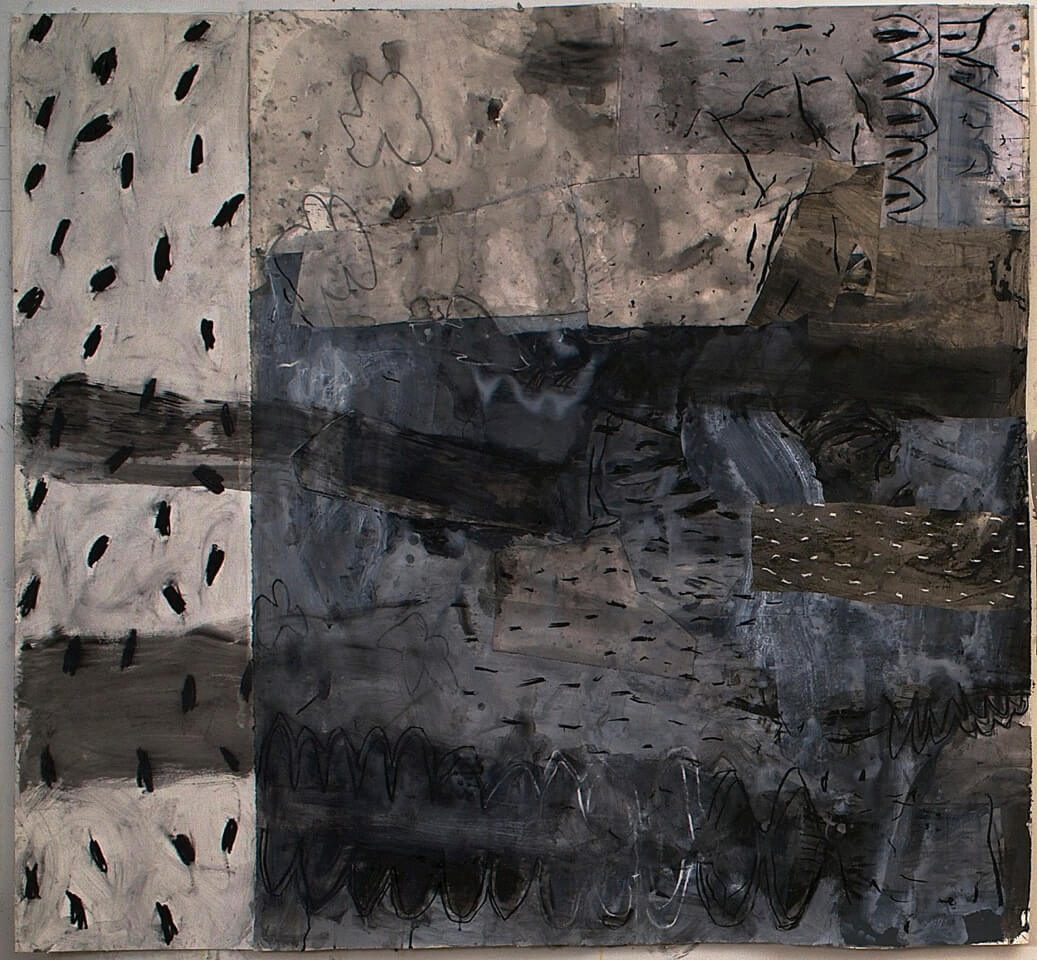

Alfredo Gisholt: Canto General

CUE Art Foundation, New York

January 30 – March 8, 2014

Alfredo Gisholt is a painter of “pictures,” a rarity in today’s art world. Unabashed in his embrace of the history of painting, Gisholt paints timeless, poetic worlds where the everyday and the grand tradition of painting merge. Gisholt and I discussed his recent work via email on the occasion of his exhibition Canto General, currently on view at the CUE Art Foundation. —Brett Baker

Painters’ Table (PT): You wear your influences on your sleeve, quoting forms from Picasso, Goya, and John Walker, to name a few. For instance, in several works a version of Goya’s Straw Mannequin is flung atop huddled masses of both gestural and appropriated forms. The mannequins, Picasso-like birds, and sheep skulls that appear in your work are very overt allusions. Their inclusion seems to mourn the disappearing tradition of imaginative picture-making while much painting today is heavily invested in theory and/or materials. Are your works critiques of contemporary painting?

Alfredo Gisholt (AG): No, they are not a critique. I don’t like to think of my painting in those terms. I have always felt that theory does not make for very good painting. In fact, it gets in the way of it. And neither does pushing material around. Painting has always felt inclusive to me – it does more than just address this one thing or this other thing. Rembrandt leaves nothing out.

All the painters you mention, and there are others, are very important to me. For years I have drawn in front of their paintings as a way of seeing them. These drawings, which I make on my sketchbook, find themselves becoming a part of the language of my paintings. After I draw them I feel I somehow own them. It is the same with a plant or a skull. Plus, I have never been afraid of influences. I also surround myself with the things I paint – a tipped over trash can, a leftover piece of steel, a lantern, etc. – and when you put all of it together there are going to be allusions. I like being a part of painting’s history and welcome it in my studio.

PT: Your work made me think of the famous Guston quote about the studio being populated with all of the artist’s influences – “friends, enemies, the art world, and above all, your own ideas.” The artist bids farewell to each, and to himself in the course of working. At the end only the painting remains. Your paintings, however, seem to have invited these influences back again, gathered them together in a heap on the studio floor. As a viewer I get the feeling these paintings are about what creates us; they suggest that the sources of our being are too meaningful to be discarded. That’s an important statement to make with a painting, yet it’s also one that risks sentimentality.

AG: I really like that description of them. I don’t understand why sentiment has become a bad word in painting. It is important for me to feel something as I paint and somehow evidence that emotion. It is a great ambition to make paint do that – Goya does. Maybe that is where meaning comes from.

A few years ago I stood in front of a large Olmec head. It had a very powerful presence – not an illusion of something, it felt real. Not too long after, I came across a small Rembrandt painting of the Deposition of Christ – it reminded me of the head I saw. It was a cluster of figures. I came back to the studio and started painting a group of figures and wanted them to feel like the Olmec head. More recently De Kooning has been a powerful presence in my studio after the show at MOMA. He titled the painting “Attic” because it had everything one would find in the attic. I put as much stuff in a painting as I think is needed to say something bigger than the objects or forms in it. Diego, my oldest son, is always asking me why I paint the dump. I tell him that Guston did it too.

PT: Your smaller works read differently than the larger ones. The scale of the elements is similar, but they have a different character. The backgrounds are more saturated in color and several feature a landscape divided by a river. The forms heaped in the foreground are dark and more indistinct, and many of the small pictures feel like night paintings.

AG: I have always made both large and small paintings. Easel size paintings are very difficult for me.

The river paintings are the last ones I did. As I mentioned, De Kooning has loomed large recently. He paralyzed me for a bit. So much so that I painted like him for a few months. During this time, I had a large canvas and decided to paint a tribute painting to Matisse’s “Turtle” painting which has long haunted me as an image – Matisse has some moments where paintings are totally unprecedented. I had Matisse on one wall and De Kooning on the other. I finished them and put them away.

In making the paintings for this show I wanted to somehow tie it all together. Neruda helped. The very early ones and smallest paintings served as a starting point. I never make studies. Most of my small paintings are made from the larger ones as a way to see possibilities. I have always felt that I need to see these possibilities and not just think of them. They also give me the chance to simplify and make some things clear. The paintings you describe are made from the last painting I finished. They opened things up again and at the same time they started to go in a different direction. Now I have to catch up to them.

PT: Yes, that’s just it – valuing the history of painting as a present, generative force. I feel that in this work and it feels genuine and deeply embedded.

I understand the paintings aren’t intentional critiques, but they do seem to inherently question the type of painting enjoying a lot of attention these days – paintings that come out of materials or theory and a modernist/postmodernist drive towards the “new,” whatever that might be. I’m thinking of exhibitions like Painter Painter at the Walker Art Center last year. Co-curator Eric Crosby, in an interview about the show, stated specifically that the artists “go where the materials take them, not where the history of painting tells them to go.”

That show also had a lot to do with bringing other mediums to bear in a painting context – painting as “a frame for contact” – as if painting needs extending beyond itself. For me, your work posits the opposite, that there’s plenty to explore within painting and that, as painters, we should immerse ourselves in the mysterious achievements of the medium. There’s plenty of positive critique in that.

AG: I want to feel that I am on the train – the train that goes back 5000 years to the art of Mesopotamia as De Kooning described it. At some point artists felt that they rather be off this train – not sure when or why it happened. There are so called artists to blame for this. Artists that felt that it was enough to point to things, to signal, to remind people of something else as opposed to make something that truly enhances life’s experience. Van Gogh changed the way we look at things – the sky was orange and the grass was blue.

I protect myself from discourse. For years I argued about those mysterious achievements in painting with some who felt it was the stuff of the past. Not anymore – I just don’t think about it. I saw the Emperor, and he is not wearing any clothes. So I make paintings with the ambition to contribute to its history. When I was a guard at the Guggenheim in Venice, I always asked to be sent to the Pollock room. I would spend eight hours in front of those paintings and draw. I would leave and go to San Rocco and see Tintoretto and they were the same thing. By the way, Pollock looks great in Venice. Theory has become the new academy – who remembers Puvis des Chavannes? I would rather be a ‘fauve’.

PT: That Pollock’s works hold their own in Venice is not surprising to me, but it’s an important context in which to view his work. In New York it is impossible to see his paintings outside the context of New York School mythology, but in Venice they’re just great paintings in the company of other great paintings.

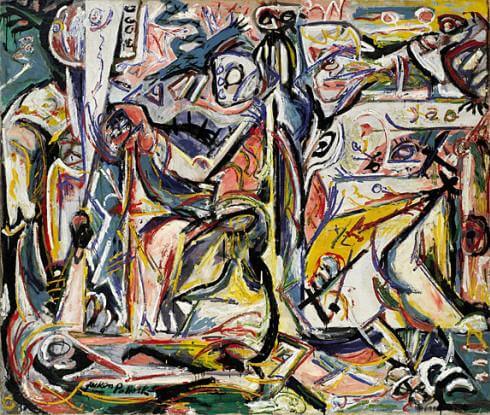

It’s interesting that you spent so much time with those particular Pollocks. The mid-40s Pollocks in Venice – I’m thinking of Circumcision (1946), Bird Effort (1946) and an Untitled painting from that same year. Forms tangle and wrestle in those works, struggling to release themselves into pure energy. Pollock, as he developed early on, felt this release of form as an imperative, but in his last works that energy begin to reassemble into figures. Those last paintings are useless to the story of Modernism but are perhaps his most significant statement about painting – that the artist must, at some point, return to the source.

AG: The forms were there to liberate his painting – to have a structure to pin things down. I drew Circumcision almost every day. You are right, Venice gave me the chance to see Pollock in a different light. I think Pollock at the end felt he had gone too far with the drip paintings, or as far as he could go. That last room at the show at MOMA – those last paintings were about starting again – going back to figuration, returning to the source. In those 1940’s paintings I saw a way to paint like Titian and Tintoretto. Pollock showed me the way.

PT: Tintoretto’s staging of figures, and combination of deep space and flat forms seems to have had a lasting affect on your work as well, except in your work they’re flip-flopped. Your figurative piles are set against flattened fields that stand in for deep space.

AG: Tintoretto was the person I discovered while in Venice. I knew the others. One day I walked into Scuola Grande di San Rocco where he painted like 20 large paintings. There was a restorer working on a small ceiling panel. The place smelled like paint! – because of the smell it seemed like the paintings had just been made. Something changed that day and I went back every day off I had.

Cézanne has me thinking of pictorial space – illusion and flatness. I do not want my paintings to be like windows, I want them to feel like a wall.

PT: Drawing from paintings seems key to gaining a deeper understanding of them. Drawing, used this way, asks vital questions – “How do these forms interact? Can I follow them? Why this way and not that way?” This kind of visual investigation is profitable to the artist and it’s fundamentally different from theoretical questioning. It’s about the artist’s (both the original artist and the one making the study) active immersion in the moment. It’s very unlike theory which is more about positioning the work and soliciting a particular response in the viewer.

AG: Drawing is the only way I have found where I can see and think visually simultaneously. It also allows me to slow down, to move across and through an image, to follow someone’s hand and internalize. I get to remake their paintings. There are so many discoveries, it answers so many questions. There are some images, I am thinking of Matisse’s Red Studio or his Bathers that are almost impossible to draw. I have tried and the drawings seem so didactic, nothing like it. I do not know what that means.

Of course there are times when I do not draw. I just look and try to leave words out of it. Talking about the Guggenheim – being a guard really taught me how to look – the time one needs to do it. After a few hours all knowledge is exhausted and you are left with this thing on the wall.

The relationship between the verbal and visual language is something that I feel that in the end can not be reconciled. Words can be very useful – the way Adrian Stokes writes about Cézanne or Lawrence Gowing on Vermeer – but they are two different things. Theory in the end mediates an experience that should not be mediated. Auerbach in an interview talking about his painting says that ‘one should not demystify that which is inherently mysterious.”

PT: Drawing seems not only fundamental to your work as a form of study, but also as a method of painting – you draw with color in your paintings. There’s not a lot of massing or “filling in” areas of color. The surfaces are filled with a variety of animating marks.

AG: I have no set ways to make things. I draw, paint and make prints and it fills my days in the studio. I do not see them as isolated activities and they all are part of one another. There is an immediacy in drawing that I really respond to. It always challenges the paintings or the paint. I love paint and I see it as a great building material, like a brick – if you add concrete you can build a wall.

What I am after is to make something that is animated – as in ‘animas’ or with a soul. I paint and touch the paintings until that happens. Sometimes it is quick and through simple means and other times it takes a long time. I think about the difference between images and paintings – as in fiction and fact. The challenge for my paintings is to become fact – for these imagined constructions feel as real as a mountain.

PT: In your artist statement you state, paradoxically, that you have “no words,” and I noticed that when you sent me images you included their sizes to establish scale, but not their titles which I thought was interesting. Am I right to think that your paintings don’t really need titles? That they really do exist outside of words for you?

AG: My artist statement is the pictures. Anything I have written in the past only approximated things – it seemed dishonest and distant. So I stopped writing and wrote that I have no words.

The images I sent you were the latest drawings and prints I made. The drawings are untitled. The prints are a suite of etchings titled “Canto General” that I made in conjunction with the paintings. All the paintings in the show are titled after poems from Neruda’s book “Canto General” and that is important. These poems have served as a structure – they have a particular tone and I always have been moved by Neruda’s poetry. Also, Mikis Theodorakis wrote music to some of them. I have listened to it for years and always wanted my paintings to sound like that. So the titles are descriptive, a description of what one is looking at – like Women of Algiers or The Third of May.

PT: One of the few things you have said about your work is that you want to “paint a picture, a marvelous large picture.” It does seem to me that that’s exactly what you do – your paintings are “pictures” in the sense that they don’t seem to need or want explanation. They are pictures because they don’t dictate a message. I can’t think of very many artists who really paint “pictures” in the way I’m trying to describe. What does it mean to you to paint a “picture?”

AG: The first time I heard someone refer to these things on the wall as “pictures” was John Walker at BU. I had always called them paintings. I found it curious and for a while the distinction was just a curiosity. But there is a difference between images made with paint and paintings, or in this case, pictures. The difference between them is not a definition in the dictionary and I will not attempt to clarify it. One of my favorite quotes by Constable speaks of the difference “The great vice of the present day is bravura, an attempt to do something beyond the truth. In endeavouring to do something better than well, they do what in reality is good for nothing. Fashion always had, & will have, its day — but truth (in all things) only will last, and can only have just claims on posterity.” That is what a picture has become in my mind.

A marvelous large picture is what turned me into a painter. El Greco’s Burial of Count Orgaz was the one. Standing in front of it I wanted to do that – whatever that was. It seemed complete and I got very emotional. That is what the ambition is – I can’t think of many artists who really paint with that ambition.