Bernardo Siciliano Pigs and Saints

Aicon Gallery, New York

November 1 – 30, 2019

In earthy, cynical realism that defends Italian sensibilities, Bernardo Siciliano’s “Pigs and Saints” at Aicon Gallery conveys the qualms of human exchange. Solid form outweighs broken surface facture that invokes the heavy Impressionism of the Macchiaioli, and sedate Italian Divisionists like Segantini. Siciliano prefers Boccioni, who passed through French Neo-Impressionist color into Futurism and too soon into the hereafter. Siciliano’s dynamism is instead tonally grounded and dwells moodily in the present.

“Social Network” is the closest Siciliano gets to levity. Colors are deftly harmonious but far from jeu de vivre. Three teenage girls with smartphones lounge on (if all the same model, slowly move across) a floral couch, legs intertwined. Each privately surfs cyberspace and attains unique plasticity, yet the trio is expertly stitched together into a space-bending pretzel. A power cord below mediates between us and them as it straddles the floor and the picture plane, warping the foreground a la Lucien Freud, whose jaundiced eye Siciliano shares. Separation and proximity, unfettered mind and dense body, transience and gravity, whimsically face off in this portrayal of new social norms.

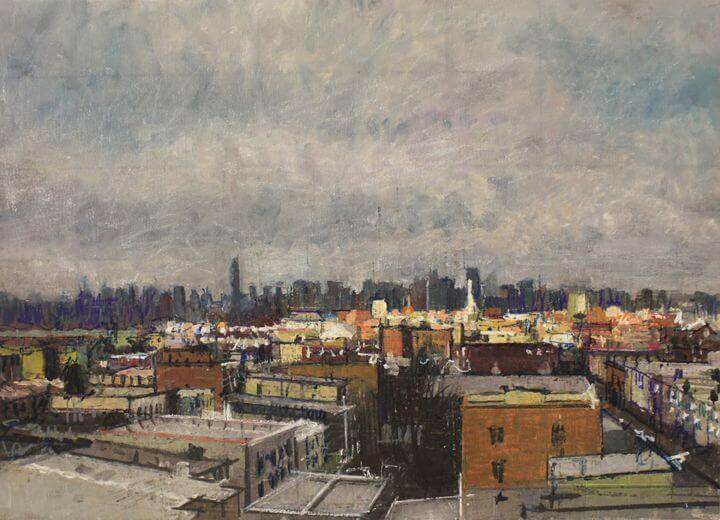

“Summer and Storm” is a pitiless vista of New York. The vertical marks of its roughly hewn sky defy calming cloud levels. An aloof palette echoes the remote viewpoint to keep all far away. Nothing romantic to see from here.

The belly of that beast is the setting for a summary judgment of random samples of humanity across the tracks in “Pigs and Saints”. The title faintly insinuates Italian profanity (porco/a), and possibly the stresses of an ex-pat in the cold, hard city.

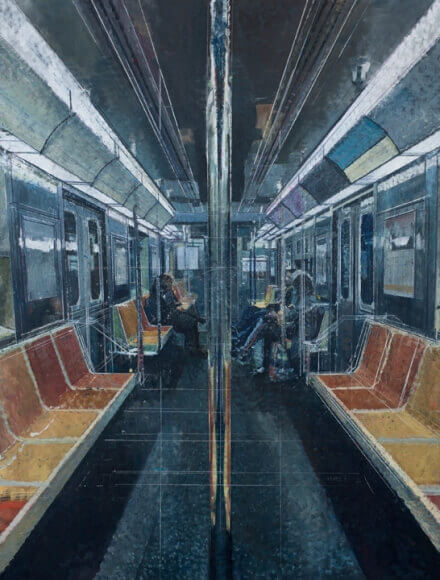

Siciliano’s references to human existence can touch the overtones of Pittura Metafisica, but with more vigor. In the sardonically titled “Tender is the Night,” a subway’s interior space intrudes into our own. Scratchy perspectival lines, left unpainted, characterize this calculated and efficient people mover. Resolution at the vanishing point is thwarted by a steel pole, as vapid, low cost lighting guides us eternally through the city that never sleeps.

The specific time indicated in the looming, beige “Monday Morning” underscores the strain of waiting. Time stretches all around an unclothed woman seated tensely at a table in a large, modern, minimalist kitchen. She stares blankly out the window without even a coffee, magazine, or cigarette to pass the time, patient as a saint. Like Balthus’s paintings, the dry, tactile surface and muted hues conjure fresco. The bland yet mysterious scene might have been collaged from photos and the artist’s memory or fantasy, and could have been inspired by Carpaccio’s “Saint Augustine”. Slow careful looking expended from one fine subtlety to the next – an empty canvas bag zooming into the foreground, an opened bill on the furry banquette – extends the present depicted in a compelling blend of unease and pleasure.

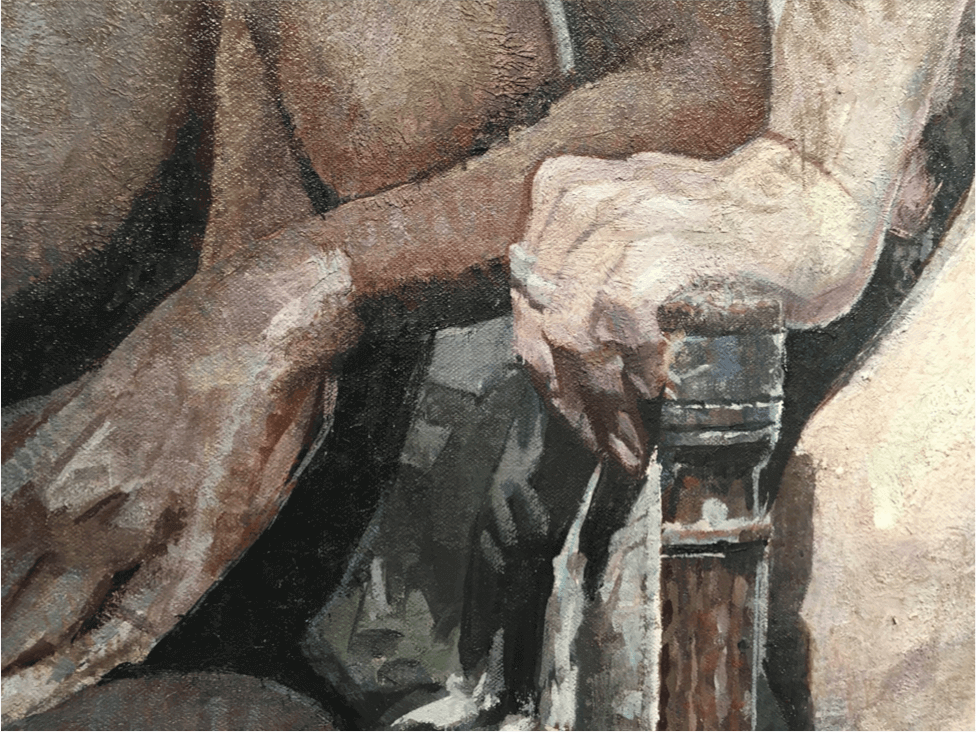

In the volcanic “Vincent Desiderio,” models pile like props, marginalized on the edge, or perch like Aeneus’s burden on the painter’s shoulder. His relaxed, counterbalanced pose contains a fierce gaze fixed to his left, reminiscent of Michelangelo’s “David” as he confronts his foe – the pressing demands of his mission. Desiderio is likewise both elegant and severe, a combination of manners rare off the runway here, but common in Italy, from opera to the street.

In the equally cagey “Selfie,” the sarcastic, earnest, and harsh join forces. The viewer, along with American political correctness and the shallow pretense of social media, are confronted with defiance. The Eakins-like frankness is sustained by unflinching fluorescent light in the cavernous studio. Ready, blue-gloved hands, and a trompe-l’oeil red splotch, cleverly divert from the shocking parts; voracious energy is subdued through work. This profane image could be the Id to the Ego of his friend Desiderio’s portrait with its saintlier focus on dedication to craft, hanging directly on the outer side of the wall.

Siciliano’s skill here in chiaroscuro and anatomy perform two excellences Leonardo catalyzed, to further the formidable sculptural quality of Italian Renaissance painting as it extrapolated into the baroque. Siciliano’s haptic and viscous flesh summons precedents like Crespi, Preti, Di Ribera, Rembrandt, and their descendants Courbet, Corinth, and Freud.

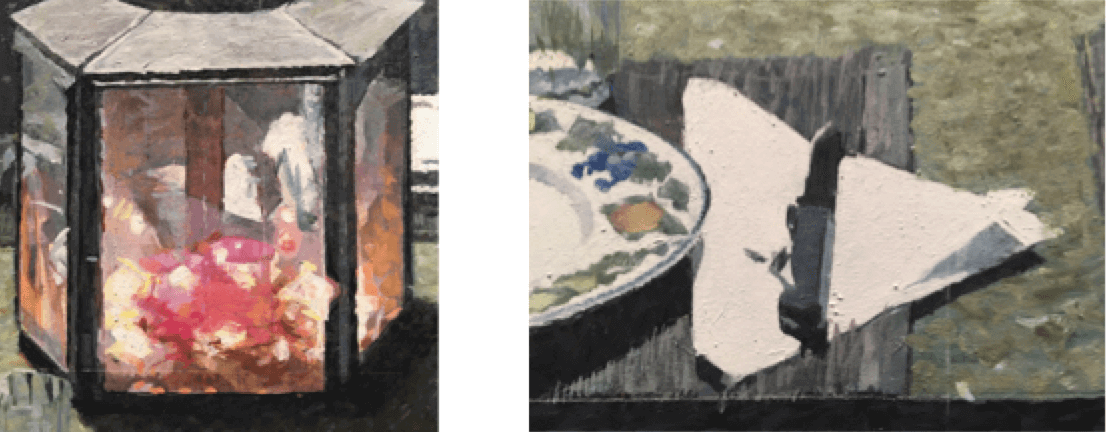

In the magnificent and overcast “Summertime,” suppers from the last ones of Leonardo and Tintoretto to Caravaggio’s ”Emmaus,” to those of van Gogh, Hammershøi, and Lopez Garcia come to mind. The unifying central seat here is empty; a matron looks vaguely off to her right as, pendulum-like, a younger person sways away to share an intimacy. The heavy focal lamp reflects a figure outside the picture but otherwise reveals little.

Whether the crepuscular scene is in- or outdoors is uncertain, but light from above spotlights portraits, lively melon slices and piles of prosciutto, precisely unoccupied chairs, etc. Between these illuminations, stark shadows don’t conceal so much as annihilate. Not unlike Caravaggio’s darks (which Wittkower described as voids), they undercut light’s promise to expose and ensure. The cool, Signorelli-like palette tempers tonal drama to slow emotion. Whatever subject Siciliano handles, misgiving recapitulates in fragmentations large and small – looping from ambiguous imagery to exacting yet distant objects to shifting brushwork and back – that can only hazard certainty. Beyond their doubts however, Siciliano’s paintings esteem the powerful legacy of Italian figurative art and its place in contemporary art.