Certain Densities

George Caleb Bingham Gallery, University of Missouri

June 3 – August 19, 2013

Featuring paintings by Matthew Ballou, Barry Gealt, David Gracie, Melanie Johnson, Ken Kewley, Rachael McHan, Rachael Pease, Emil Robinson, and Megan Shaffer.

Below, in an essay written to accompany the show, Matthew Ballou argues that “a perceptual approach to painting is not synonymous with rote observation.”

Two Asides Regarding Perceptual Painting

1

Appearances reach us through the eye, and the eye—whether we speak with the psychologist or the embryologist—is part of the brain and therefore inextricably involved in mysterious cerebral operations. Thus nature presents every generation … with a unique and unrepeated facet of appearance. The encroaching archaism of old photographs is only the latest instance of an endless succession in which every new mode of natural representation eventually resigns its claim to co-identity with natural appearance. And if appearances are thus unstable in the human eye, their representation in art is not a matter of mechanical reproduction but of progressive revelation.”

—Leo Steinberg i

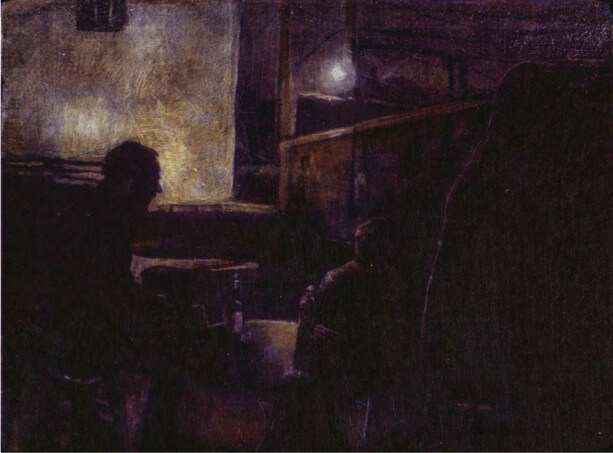

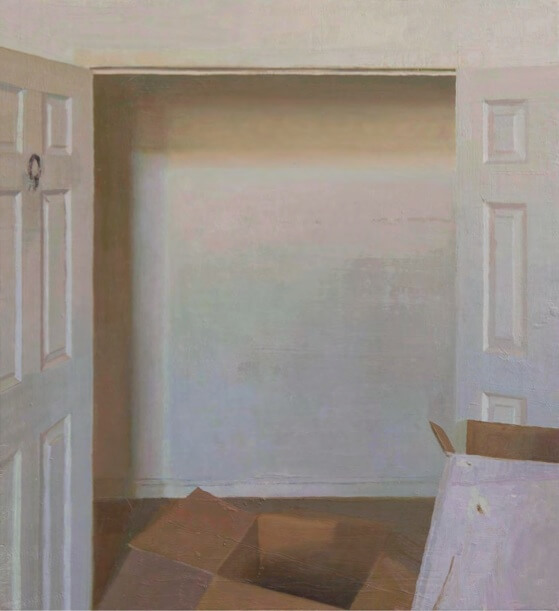

Although quite varied in manner and approach, a number of the works in this exhibition evidence a determined sensitivity to the painted surface as an aesthetic and formal reality. This embrace of surface is necessary, as all paintings come down to the particular arrangement of pigments on a (usually) two-dimensional plane. Painted surfaces are always progressively revealed; they always manifest over some period of time and through some process of engagement. Surface could be defined as a zone of incidence where nuanced sight and kinesthetic touch come together. The artist’s apprehension of space, light, form, and movement presents itself as a haptic environment in the painted object. This arena is of huge significance to perceptually-minded painters.

Creating an illusion of things is of only partial importance when it comes to the fact of the painted surface. Subjectivity, shifting focus, and temporality are also vital as indicators of life, sensation, and thought in the artwork. These ephemeral aspects of creative effort become embedded, and they shape the painting’s meaning just as surely as any material or formal fact might. Therefore the densities of this exhibition’s title refer not only to paint but also to lived experience.

The densities these surfaces support are certain in the sense that they are resolutely made. However, they are also certain in that they are particular and specifically sought-out. These surfaces are a realm of peculiar notations drawn together to form a united structure combining sight, touch, and contemplation in an evocative way. This rich atmosphere is a unique aspect of what art has always offered makers and viewers. The works live as artifacts of experience, as discursive objects that both reveal and conceal their own making. Thus, the paintings are not meant to function as closed events. Instead, they are participatory and relational. Their surfaces offer an exchange with the audience that inspires reciprocity and active viewing.

2

“When the limits of the depictable in nature suddenly recede before the searching gaze, when earlier works come to seem inadequately representative of truth, then the artist’s power multiplies… Every picture is to some degree a value judgment, since you cannot represent a thing without proclaiming it worthwhile… But natural fact can be purely apprehended only where the human mind has first endowed it with the status of reality. Only then is the act of seeing backed by a passion…”

—Leo Steinberg ii

A perceptual approach to painting is not synonymous with rote observation. Perception is a harrowing experience, fraught with lightning-strike insight and rabbit-hole tunnel vision. Perceptualists recognize that their sight is subjective, the result of influence and pressure, and extremely sensitive to suggestion and conceit. They know that building a picture from their own shifting apprehension of the environment around them is not a linear matter. The most banal thing may become charged with transcendence through a concerted effort of contemplation. Likewise, the most sacred object may be reduced to the realm of prosaic commonality via determined focus on other concerns. In each instance a keen awareness of sight may be obtained without limiting the painting to an exercise that terminates in simply achieving an image. Perception is more than the act of seeing, just as listening is more than the act of hearing. Perceptual painters are aiming to experience more – and present more in their work – than seeing and translating sight, no matter how honorable an end that may be. Verisimilitude is only one aspect of representational art. Other aims may take precedence in any particular painting.

Achieving a distinctively felt sense of the seen in a work may actually involve the most rigorous abstraction, the most intense formal play. Indeed, it requires artists to go far beyond just transferring identifiable things (objects, landscapes, people) from the three-dimensional realm into the two-dimensional realm. This is because representation often involves counterintuitive understandings of time and awareness, proportion and relationships, memory and history, among many other factors. Representation is an accumulation of such multiplicities. A representational picture will not always look representational, but it will always communicate beyond appearances.

To arrive at a picture that embodies representation artists may have to forgo depictive, clear tropes in favor of the kind of digressions that so often permeate our sensations. The visual dynamics of sight are far more complex than simple transcription of accurate features, textures or shapes. They are the result of complex neurobiology and social conventions interacting with the idiosyncratic ways each of us has learned to see. How viewers comprehend a picture is intimately connected to the previous experiences of sight they have had, how they have interpreted those past experiences, and what vast range of factors (physical, emotional, cultural, religious, etc.) have influenced those experiences. The perceptual painter, incredibly, attempts to build pictures with all of these various elements in play. That is why Cezanne’s apples are not just apples and why Heidegger iii and Meyer Schapiro iv can argue about Van Gogh’s boots. An artist concerned with channeling being-ness and experience will never settle for illustrative mimesis. With great honor for appearances, the perceptualist reaches beyond them.

So it is that many of the images you find in this exhibition are cumulative estimations exploring potential states of experience rather than final products of confident certainty. Perceptual painting rests on a constructed visual logic that has little to do with direct visual facts. It incorporates tangential awareness into the acts of apprehension, asking much of both the artist and the viewer. When you look at the paintings, see beyond appearances into the subjective realms these artists have created. In paying attention to what others have contemplated, we participate in something far deeper and more intimately human than mere imitation could ever provide. Mine your own personal history of sight and trade literal, certain readings for evocative and relational ones. Perhaps you will perceive the reveries these artists have felt, grasp the “progressive revelation” they have suggested, and notice the poetic understanding embedded in your own alchemical vision.

These things are, after all, part of what paintings were always meant to do.

“The aesthetic is the making formal of epiphany. There is a ‘shining through’.”

—George Steiner v

Notes

i Steinberg, Leo. Other Criteria: Confrontations with Twentieth-Century Art. London, Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 1972. 292-293.

ii Ibid. 296-297.

iii Heidegger, Martin. Basic Writings. New York: HarperCollins, 2008. 143-212.

iv Schapiro, Meyer. Theory and Philosophy of Art: Style, Artist, and Society, Selected papers 4. New York: George Braziller, 1994. 135-142; 143-151.

v Steiner, George. Real Presences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989. 226.