Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life, 1928–1945

The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.

June 8 – September 1, 2013.

Conversations about about Cubism most often begin with Picasso, but none can exclude Georges Braque, his quiet and more hermetic co-inventor. Though overshadowed personally by Picasso, Braque played an unquestionably important role in developing modernism; he was a lesser participant in Fauvism before making his most significant contribution as a Cubist and as the inventor of papier-collé. Yet it could also be said that as significant as these achievements were, they were tightly bound to group aesthetics, and never entirely his own. Braque was well aware of this, recalling that his Cubist paintings were “anonymous… there was no need for them to be signed.” 1 Only in his paintings after World War I did Braque’s individuality emerge.

The title of the current Phillips Collection exhibition, George Braque and the Cubist Still Life, would suggest it reinforces the art historical need to legitimize Braque through his association with Cubism. Instead, the paintings on display confirm that Braque’s “second career” may, in retrospect, constitute his greater legacy.

Leaving the technique of “little cubes” behind, Braque continued to build on the language of Cubism – primarily its complication of space. He sought what he called a “manual” space” that embodied the “rapport [that] exists between [objects] or between them and myself.” This notion was born of what Braque described as “the yearning I have always had to touch things and not merely see them.” 2

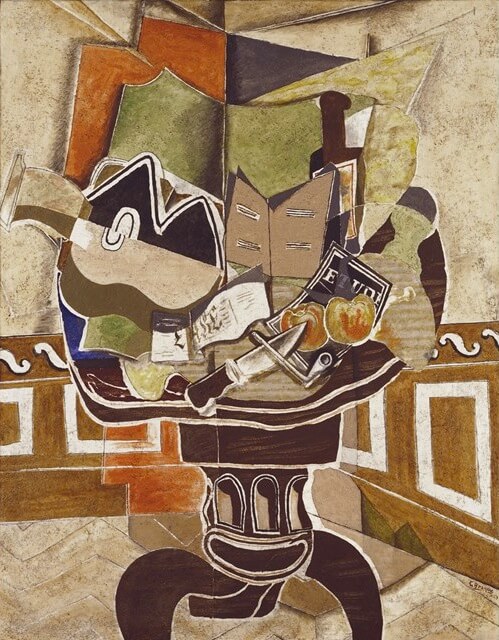

The Phillips’ own great The Round Table (1929) opens the exhibition surrounded by smaller yet equally impressive still life canvases from the 1930s and 40s. Scanning the room, one gains an immediate understanding of what “tactile space” means. The objects in each canvas pulse with a sensitivity to physical pressures within the natural world. The paintings are full of distortions, yet these distortions feel right because they cue an awareness of our own perception of physical forces.

Four large, oblong paintings dominate the next gallery. Originally commissioned by art dealer Paul Rosenberg, they are reunited here for the first time. It’s interesting to see a site-specific suite, but the paintings lack, as commissions will, the true visual and technical adventurousness of studio paintings. They will send the viewer back to the first gallery to admire works such as Fruit Dish and Fruit Basket (1928). One of the best examples of Braque’s commanding and sure draftsmanship in paint, this picture throbs with the intensity of complete intellectual engagement. The Rosenberg paintings, by comparison, feel more rote and contain rather too many of Braque’s painterly effects – the faux green marble of The Napkin Ring (1929) being the most obvious example. These effects call too much attention to themselves – displayed rather than deployed in response to the needs of the paintings.

The third gallery houses what may be Braque’s most bizarre and exuberant canvases, primarily from the 1930s. The room is loud, even joyous, and the works are cacophonous symphonies of extremes. Braque’s palette in these works plays highly saturated oranges and reds against dusty pinks, salmons and pale grays. His drawing features both jagged and languidly contoured forms. Most striking are the surfaces – extreme examples of Braque’s method of adding sand to his paint. The sand’s heavy grit creates a surface that both reflects the ambient light and deepens that within the painting. In combination with the gentle outlines and washes with which he paints the objects, the sand creates a surprising fullness of space, as if seen through dust illuminated by broad beams of light. In paintings such as Fruit, Glass, and Mandolin (1938), Braque has managed a prescient, all-over painting that also operates as atmospheric perspective. This is characteristic of Braque’s approach, in which he collages techniques to better evoke the visible world in all its complexity.

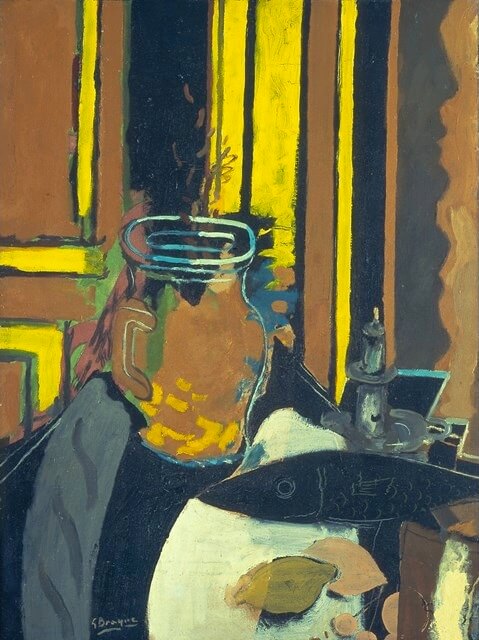

Following a corridor displaying ephemera and the painting Still Life with Pink Fish (1937), the coloristically tamer fourth gallery shows Braque in complete command of his vision with several masterful canvases including The Gueridon (1935).

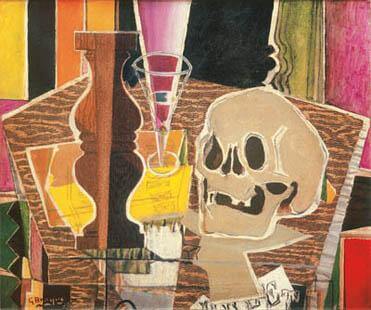

By the last gallery, there is a palpable sense of a new, manmade force acting on Braque and his objects – the onset of the second World War. His tables serve up overt religious symbols including blackened fish and a chalice. His incandescent yellows and oily blacks evoke the sickly illumination behind a blackout curtain. Skulls appear, looking much like the palettes that lay near them. In the Studio with a Black Vase (1938), a skull sits turned away; its sutures rendered realistically. Their zig zagging forms mimick the colorful yet increasingly fractured space of the painting even as they mock its lively luminosity. To the left, Mandolin and Score (The Banjo) (1941) offers a more playfully depicted palette, painted as part of a musical instrument – yet the lurid color suggests a mournful song, and the table is draped in red, sharp forms.

Despite these visual clues, Braque’s work was criticized due to its seeming lack of politics. Overt political engagement was seen as a highly desirable component of avant-garde art. Contemporary works such as Picasso’s Guernica (1937) and Joan Miró’s The Reaper (1937) were obvious protest paintings. In both cases the artists adopted specific political events as subjects. In contrast, Braque’s subject matter remained unchanged; he continued to paint studio still lives. His inclusion of traditional vanitas elements hinted at but did not rage against the grave events at hand. Such subtlety was seen by many as an indication that Braque was out of touch with both society and the direction of modern art. Even those who praised his work cited its “offensive calmness.” 3

Any notion of Braque’s indifference erodes in the presence of these paintings. Standing before them, it’s clear Braque approached the world war dead on and with open eyes. He concentrated on what was close at hand, venerating through scrutiny what would be hardest to replace, the commonplace. His finished works are elemental arrangements of familiarity governed by balance and order. They are an antidote to the willful tearing down of homes and cities Braque saw around him.

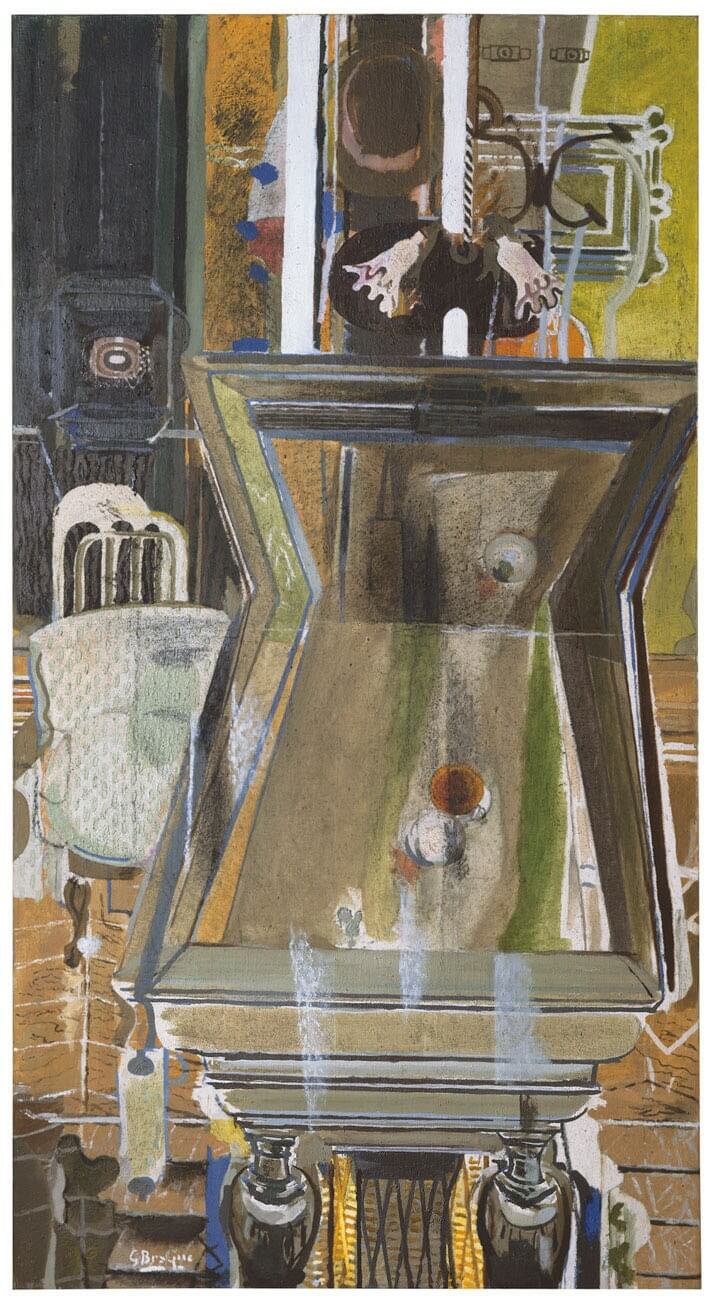

Only after the war ended did Braque’s paintings begin to change. He began to include more expansive interior spaces. These new paintings would culminate several years later in his great “Studios,” some of the most deeply developed visual tableaus in 20th century painting. Sadly, no examples of the “Studios” are included in this exhibition, but fascinatingly complex paintings such as The Billiard Table (1944-52), begun just after the liberation of Paris, are. They hint at the greatness still to come.

It is hard to make it through this exhibition without being waylaid by one or more paintings, even within a single gallery. Any number of Braque’s paintings could sustain and renew a viewer’s interest for a lifetime. This quality of renewal, the sense that simple subjects can be generous, that they contain more and different experiences to reveal, is more scarce in painting (and in life) than many care to admit.

Notes

1 Alex Danchev, Georges Braque: A Life, Arcade Publishing, New York, 2012. p. 112.

2 E. Mullins, Braque, Thames & Hudson, London, 1968 – quoted in Gordon Hughes, “Braque’s Regard,” Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life, 1928-1945, DelMonico Books, Prestel, Munich, London, New York, p 87.

3 Jean Babelon, “Braque et la nature morte” – quoted in Karen K. Butler, Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life, 1928-1945, DelMonico Books, Prestel, Munich, London, New York, p 25.