Hao Liang: Portraits and Wonders

Gagosian Gallery, New York

May 6 – June 23, 2018

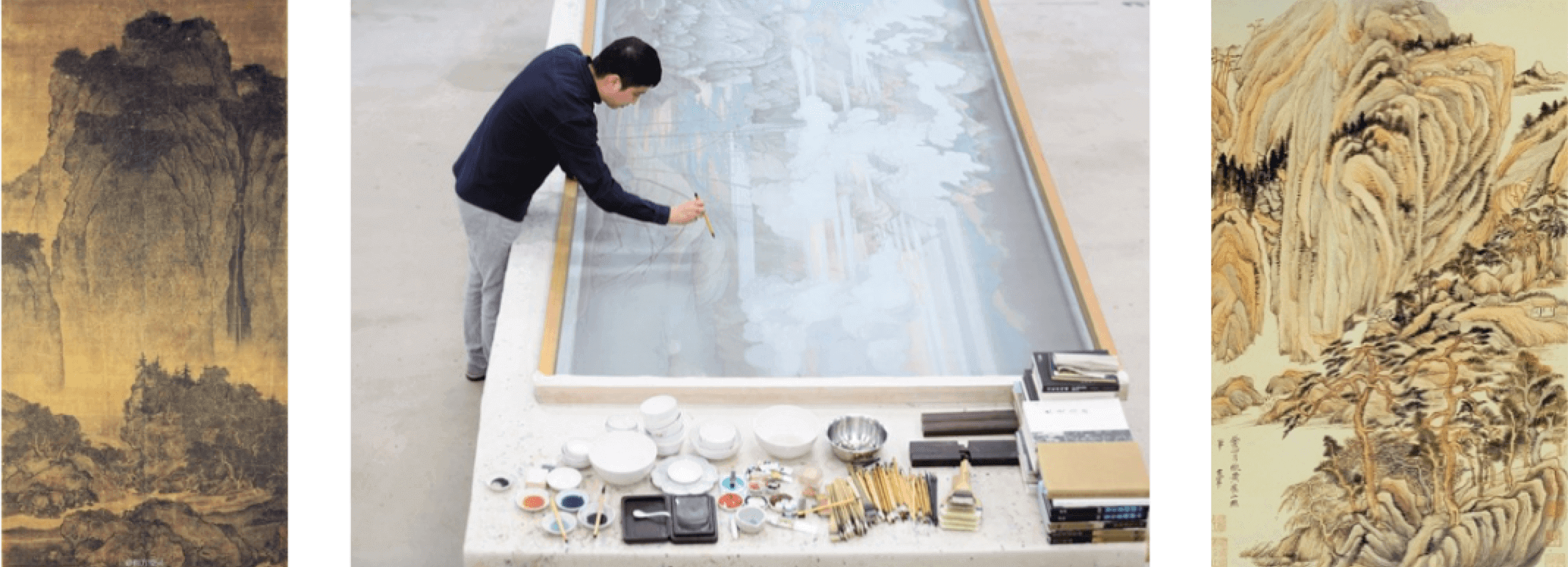

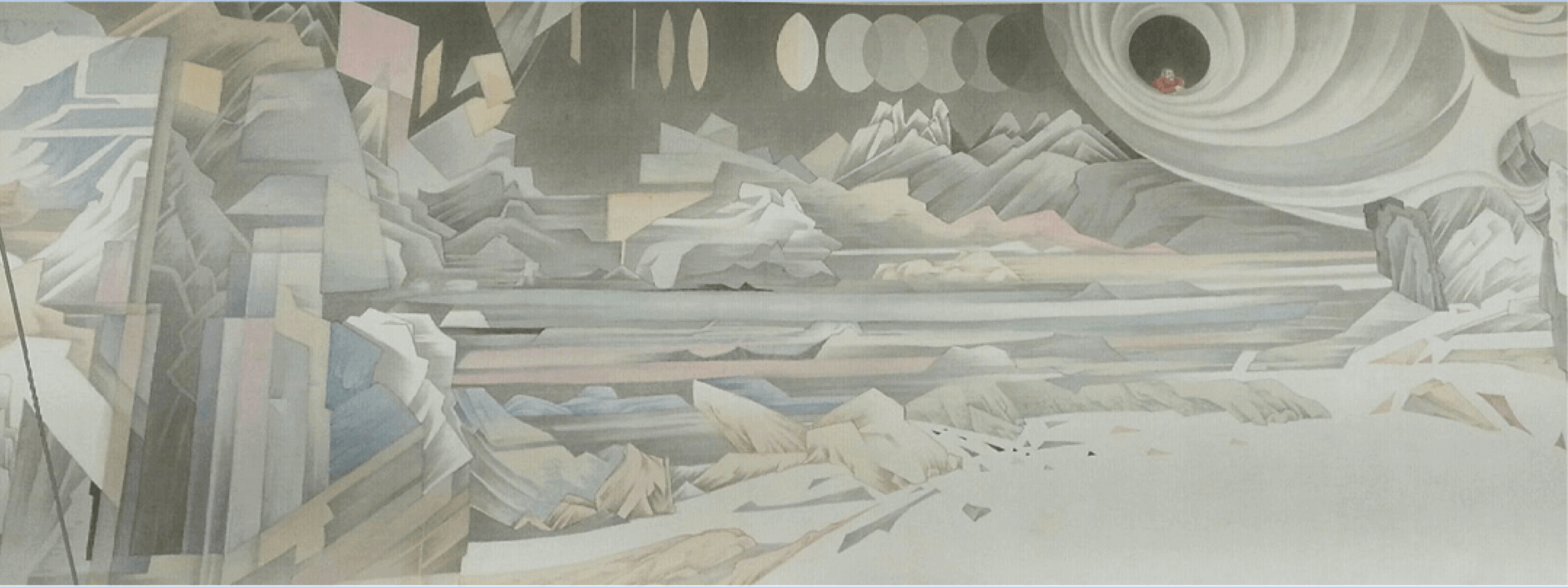

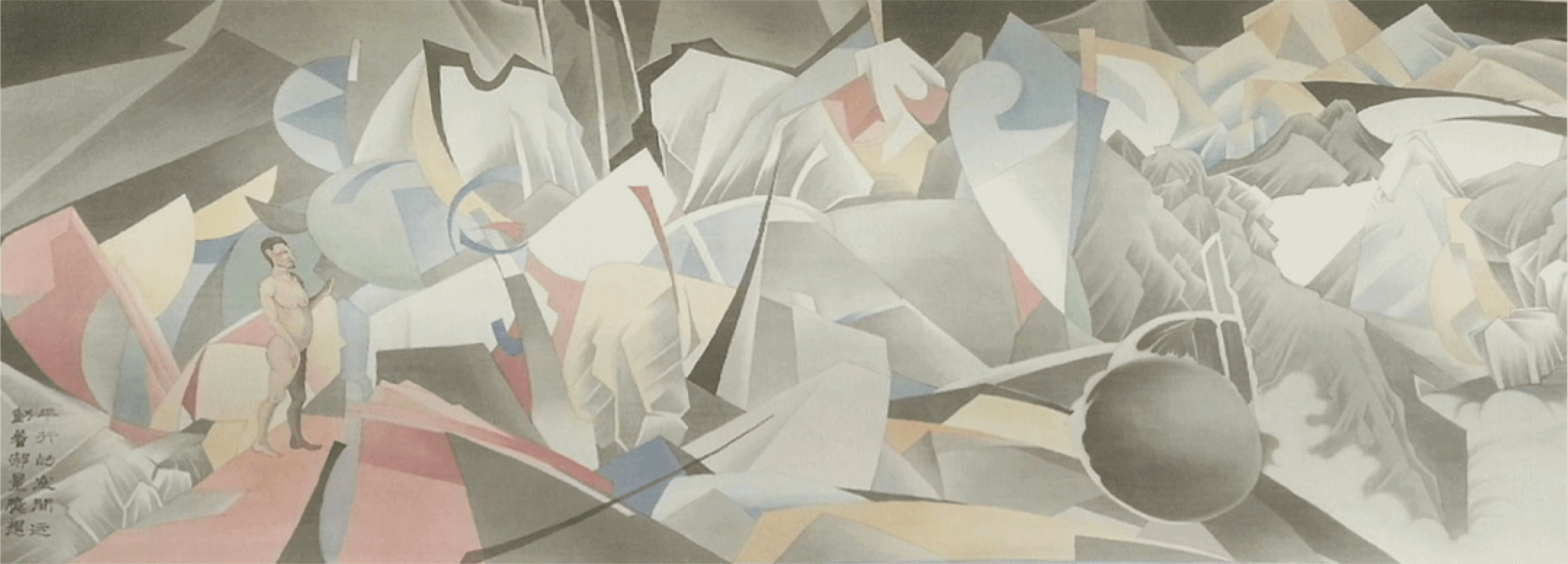

In elegant blends of old and new, Hao Liang’s “Portraits and Wonders” honors Chinese painting’s great landscape tradition as it abates its current “anxious relationship between the ancient and the modern”. 1 Large landscapes are interspersed with smaller portraits that stylistically defer more overtly to the past. Stretching thirty two feet, “Streams and Mountains Without End” activates the span from silk painting’s 5th c. BC origins, through medieval Chinese literati painting, to European modernism and contemporary cartoons. Its presentation, inset at an angle along the wall, intimates the slow unscrolling the Song literati painters Liang emulates would have performed for their conoscenti. Subdued tones and subtle color further solicit a close reading.

Though technically read from the right, where a face leads us into intertwining natural and abstract forms, eastern and western orientations are availed by its placement in the gallery and underlined by its chiasmus composition. 2 A sampling from Kandinsky’s “Seven Circles” (1927) joins the action midway.

Unable to see many literati masterpieces firsthand, Liang studied them in books. Chinese art had been heavily pilfered during colonial conflicts, and as the 20th c. republic usurped the imperial dynasty. 3 Many shan shui (mountains + water; ink landscape) paintings were destroyed in Mao’s 1949 communist and then Cultural Revolution (1966-76) iconoclasms, though troves were secreted to Taiwan. 4 Rejecting both shan shui as too ancestor-worshipping and “art for art’s sake,” Mao adapted oil painting (introduced earlier by Chinese artists studying in avant-garde Paris) to aspirational Soviet social realism to uplift the masses. Economic and educational reforms 5 since Deng Xiaoping, however, have increased higher education (still highly selective) and study abroad. Stylistic constraints have relaxed, and Chinese painting is now dynamic in the international market.

Like cast drawing’s function in the French Academy, realism was foundational at Liang’s (b. 1983) art school. He then returned to earlier quests, copying Fan Kuan’s (990-1020) Song masterpiece “Travelers by Mountains and Streams.” Like Liang’s work it is on silk, requiring careful preparation – versus paper, which allows painterly flourishes 6 (Silk screen printing was also invented in China).

Painting thrived during the Song dynasty (960-1279), when a meritocracy that synthesized Taoism and Chan (forerunner of Zen) Buddhism into Neo-Confucianism replaced hereditary aristocracy. Literati (scholar-officials) 7 like Fan Kuan, disillusioned after successive dynastic upheavals, became artist-recluses. The literati’s harmonious, all-seeing views, with mountains as rulers and pines upright citizens, might contain veiled political critiques. Their private self-expression conjures modern artists a millennium later more than their contemporaries in medieval Christian monasteries ornamenting their copies of ancient texts. While we know little about these European calligraphers beyond who they worked for, Chinese scroll paintings, empowered by centuries of continuous humanism, were annotated through the ages with poetic responses and seals, recording personal thoughts, names, and owners. Liang, too, enhances his descriptions with poems that inspired him.

In Europe calligraphy gave way to illuminated manuscripts and then painting. Movable type (invented in China) and the printing press allowed Protestants to evade papal authority and study the Bible directly, encouraging literacy. But calligraphy in China remained elite, official communication, like Latin and Greek in Europe – no doubt partly due to complexity: today there are 50,000+ Chinese characters, an educated person knows about 8,000, one can get by on 2500. Inherently pictorial, the imprecision of the Chinese language may lend itself to poetic inference.

While there are debates over just how far back poetry and painting intersect, 8 learning to write 9 entailed fluency with the brush and mastering official styles long practice (something like hand-copying fonts today). Established by the 8th c., the Three Perfections – poetry as painting with sound, painting as silent poetry, calligraphy as “the delineation of the mind” 10 – share affinities with Kandinsky’s synesthesia 11 – colors that suggest sounds, cycles of paintings as symphonies. In the USA Kandinsky is associated with Europe (abstract art and Bauhaus), but his inspirations included not just shamanism, folk and primitive but, like Mahler and Pound, East Asian art 12 – an antecedent Liang shares.

In “Streams and Mountains Without End” Liang explores affinities between the art theories of Kandinsky and of painter-connoisseur Dong Qichang (1555-1636). Qichang described differences – between Northern (individually expressive) and Southern (dutiful to positive appearance) Song styles – not unlike his Italian near-contemporary Vasari, or Wölfflin’s later art historical codes. Like Kandinsky, Qichang was also a progressive spokesman. He encouraged painters to decline veneration through imitation (typical of iconic traditions) for studious originality.

Liang equates post-1949 China’s relationship to its artistic past to that of the USA’s to Europe. No doubt also drawn to Kandinsky’s experimentations from Fauvism to expressionism to biomorphic and geometric abstraction, Liang approaches art history unencumbered. His cross-pollinations have sympathies with the Japanese remake of “Metropolis,” with animation’s closed forms and the levity of illustration, like the anti-heroic graphic novels of Chris Ware.

But this painter’s impulse is to elaborate historical ideas with the temporal freedom of Thomas Cole – or with the formal complications of Kandinsky. Not unlike the recent animation of a Song masterpiece by Zhang Zeduan, 13 he wants to renovate the two-way bridge to the literati. Liang describes contemporary Chinese painters’ desire to “break through time and space… to understand where our modernity comes from.” His impressive wonders show a way.

Notes

1 Liang quotations and biographical references from interview with Philip Tinari in “Hao Liang: Portraits and Wonders” Gagosian catalog

2 “Looking to the Future,” essay by Loic le Gall in “Hao Liang: Portraits and Wonders” Gagosian catalog

3 “…at least 17 million Chinese cultural relics are scattered all over the world, far more than are housed in China’s own museums… ” – http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/epaper/2014-02/21/content_17298439.htm

4 https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/asia/china/articles/The-best-of-historic-Chinese-art-lives-in-Taiwan-Tales-of-the-Unexpected/

5 http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.2304/pfie.2004.2.1.4

https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2015/01/what-students-in-china-have-taught-me-about-us-college-admissions/384212/

6 “…applying paint to a silk surface requires more painstaking techniques, building up ink and colors carefully and gradually in layers. Paper, in contrast, is more absorbent and is favored for spontaneous effects…” – https://depts.washington.edu/chinaciv/painting/4ptgtech.htm

7 https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/chin/hd_chin.htm

8 James Cahill lectures – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KJ4S-jCh4iE

9 https://www.diggitmagazine.com/papers/pick-pen-forget-how-write-character

10 https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/three-perfections-poetry-calligraphy-and-painting-in-chinese-art/

http://poetrychina.net/wp/calligraphy-painting/the-three-perfections

11 https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2006/jun/24/art.art

12 https://dornsife.usc.edu/news/stories/1488/shamans-and-the-russian-avant-garde/

13 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PiOVb56eWLg