Audubon to Warhol: The Art of American Still Life

Philadelphia Museum of Art

October 27, 2015 – January 10, 2016

O Nature, and O soul of man! how far beyond all utterance are your linked analogies! not the smallest atom stirs or lives on matter, but has its cunning duplicate in mind. –Ahab

Herman Melville, Moby Dick

Roman, Italian, Spanish, Dutch and French. These cultures all developed uniquely mannered still-life traditions that so codified the cultural gestalt of each that the works carry associations far beyond visual culture into political, economic and religious history. What about American still-life painting? Have we ever witnessed a stylistic zenith in which our culture’s most critical ideas were codified in the still-life? Are there American painters who captured the cultural zeitgeist the way our greatest novelists and musicians have? Do we have a Zurbarán, a Chardin or a Cézanne? These questions, and many more, come to mind while viewing The Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Audubon to Warhol: The Art of American Still Life, an ambitious, scholarly show that traces American still-life painting back to its roots at the birth of our society.

Audubon to Warhol gathers the works of nearly one hundred still-life painters, spanning two centuries, and separates them both chronologically and thematically into four groups: Describing (1795-1845), Indulging (1845-1890), Discerning (1875-1905) and Animating (1905- 1950). These categories give the show some structural support, and help one navigate a sea of images, each of which offers a compelling glimpse into American cultural history.

Our early still-life painters worked from one of two imperatives: a scientific approach to describing discrete natural elements as faithfully as possible, or the more painterly approach of rendering entire scenes illusionistically. Both approaches have their roots in European painting, but a triumph of the show is its suggestion that these modes of working were distinctly American, too.

The first mode is of artist as naturalist, rendering nature faithfully so as to gain a better understanding of it. The second is of artist as magician, conjuring life in paint with a vaudevillian sleight of hand. Such masterful facility motivated the work of Raphaelle Peale, the most accomplished son of Charles Wilson Peale, scion of America’s First Family of painting. Raphaelle’s twin “deceptions”— Venus Rising From the Sea—a Deception (1822) and Catalogue Deception (1813)—open the show. Both paintings play with the illusionism of depiction, and one cannot help but be drawn into their world. Venus Rising is a kind of painter’s pun, showing a white linen cloth hanging from a bit of ribbon. The cloth, rendered with absolute naturalism, covers most of a painting of what promises to be a lovely nude. Under the cloth’s bottom edge a creamy white foot stands on tiptoe. Above it an arm reaches up to tease out a mane of flowing blonde hair. It’s a witty painting. The absolute realism of the cloth and knowledge that we’ll never see what lies beneath it connect the work to the very beginnings of the still-life genre in ancient Greece.

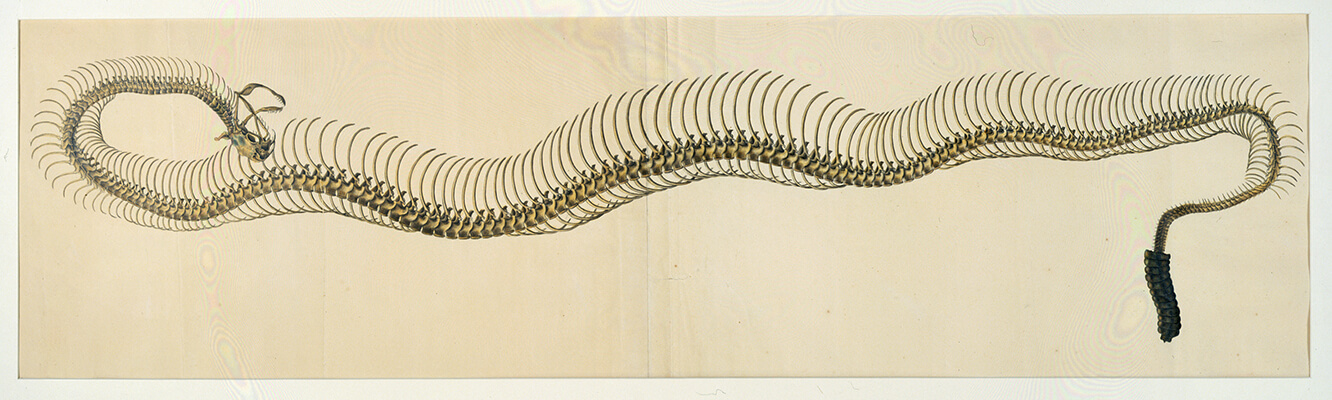

Equally good is the work that stems from the scientific imperative, introduced here by a magnetic pairing of drawings by John James Audubon and Benjamin Henry Latrobe. Latrobe’s Rattlesnake Skeleton (c. 1804) shows in minute detail every vertebra and delicate rib of the snake’s body as it stretches over two long sheets of creamy paper. It is as if the snake sits before us in the bright light of the lab, perfectly preserved for study. Audubon’s Pennant’s Marten is depicted in full flesh and blood, snarling in a menacing crouch. It is one of a handful of Audubon drawings in the show, each of which renders its subject in life-like detail.

Fascinating as they are, the drawings of Latrobe and Audubon seem equally suited to the natural history museum as the art museum. Such is the chief delight, and paradox, of the show: both strains of early American still-life—Audubon’s scientific realism and Peale’s painterly illusionism—seem, in the context of western art history, less like “art” and more like “history.” It’s a nagging feeling that begins with the early works and persists right on through to the exhibition’s end. Viewing one painting after another, nearly one hundred in all, one can’t shake a growing suspicion that the works on view are but a fringe player in a larger drama of cultural identity.

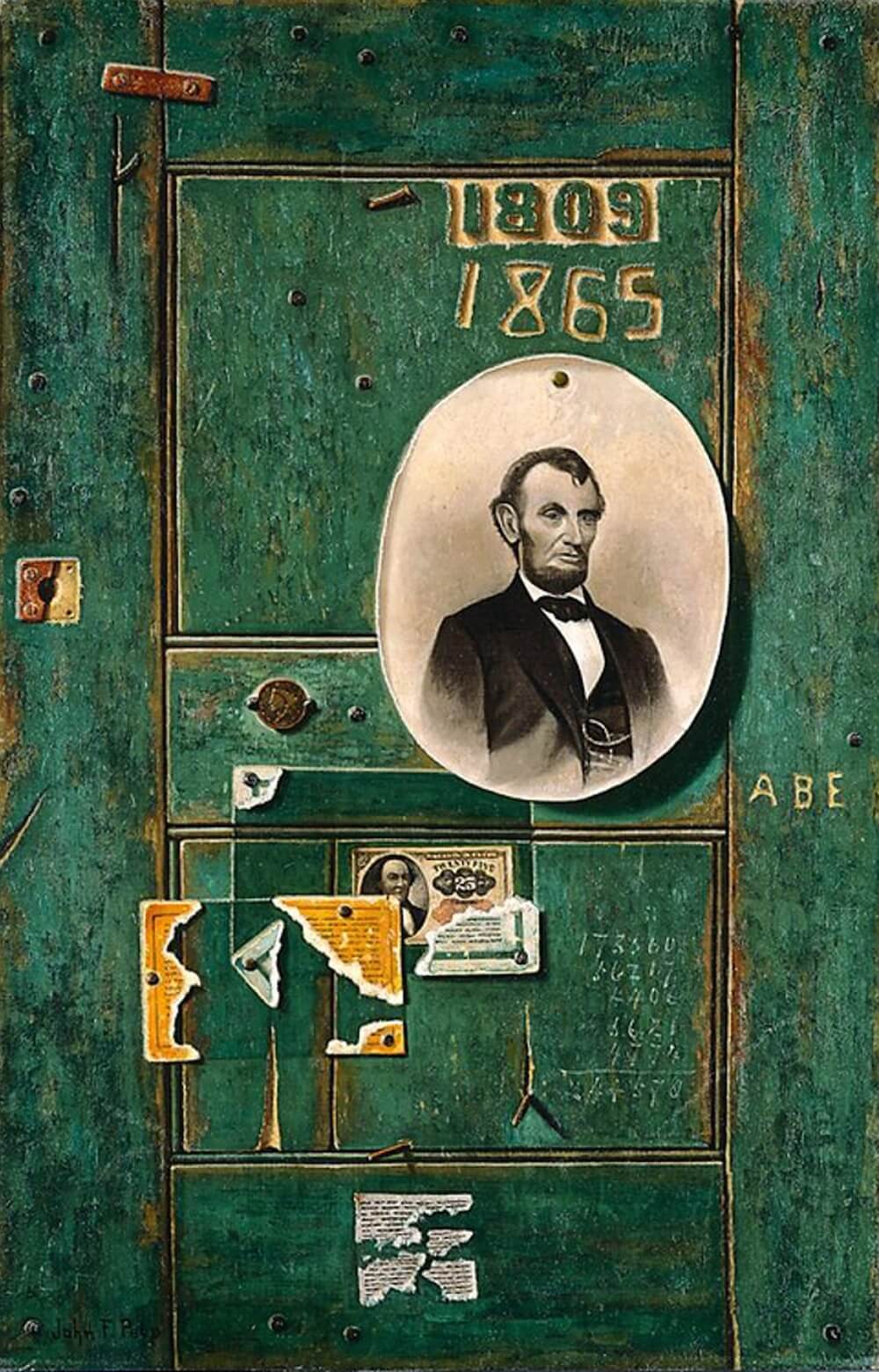

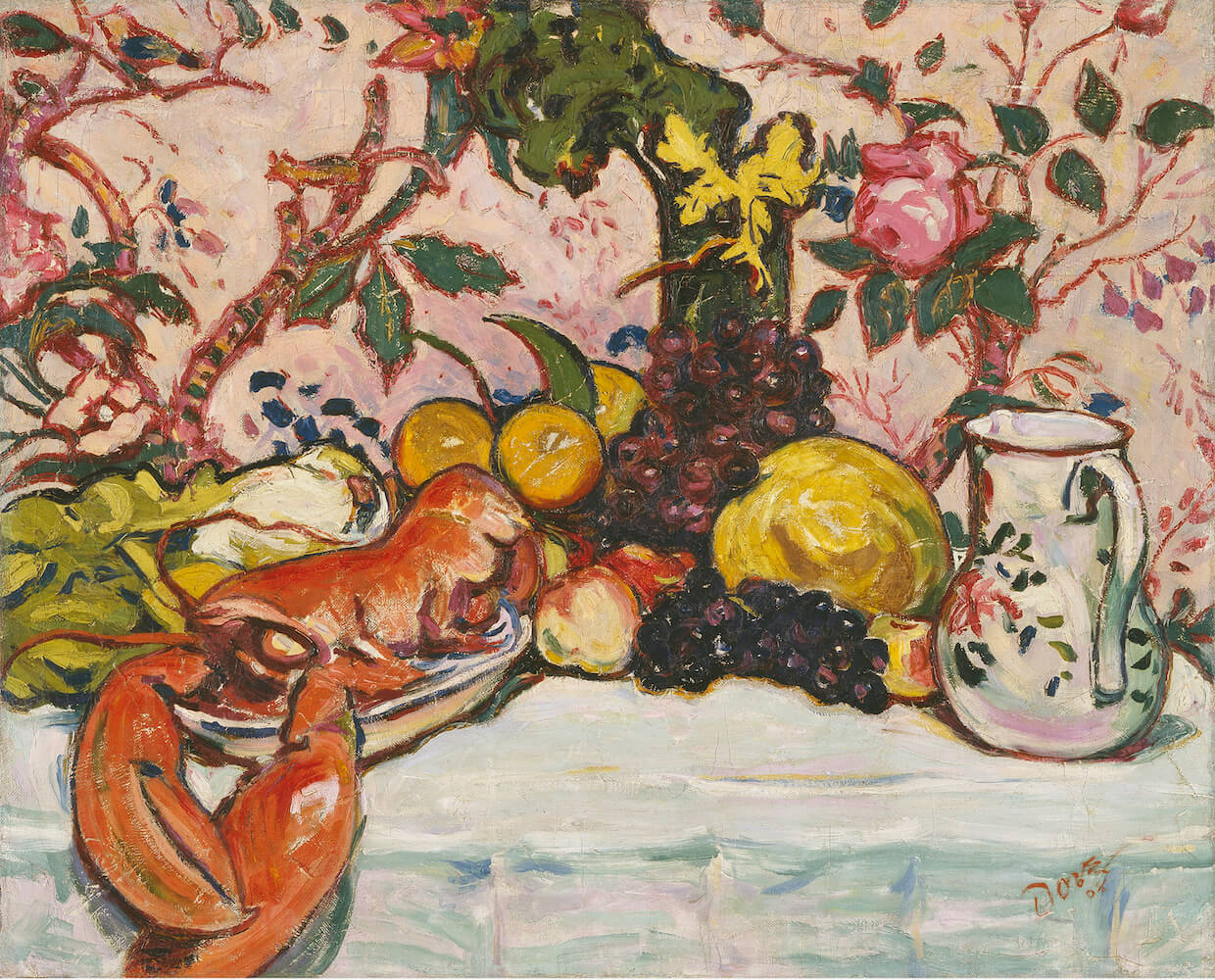

From the mid 19th century to the early 20th, the periods covered here under “Indulging” and “Discerning,” the strictly scientific imperative evaporates and painterly illusionism is employed in the service of still-life-as-metaphor, a Victorian formulation in which every element of a composition has clear symbolic meaning in the culture at large. Severin Roesen’s Flower Still Life with Bird’s Nest (1853) is a lush picture of a vase bursting with exotic flowers. Each would have conveyed a particular message to the painting’s viewers. Painted to provide the focal points and conversation pieces for America’s increasingly opulent homes, the Victorian strain of symbolic still-lifes is perhaps the closest we get to a unified still-life language. But such painting is also a kind of feint, communicating in a system of recognizable symbols, and in so doing subverting true cultural fluency in painting.

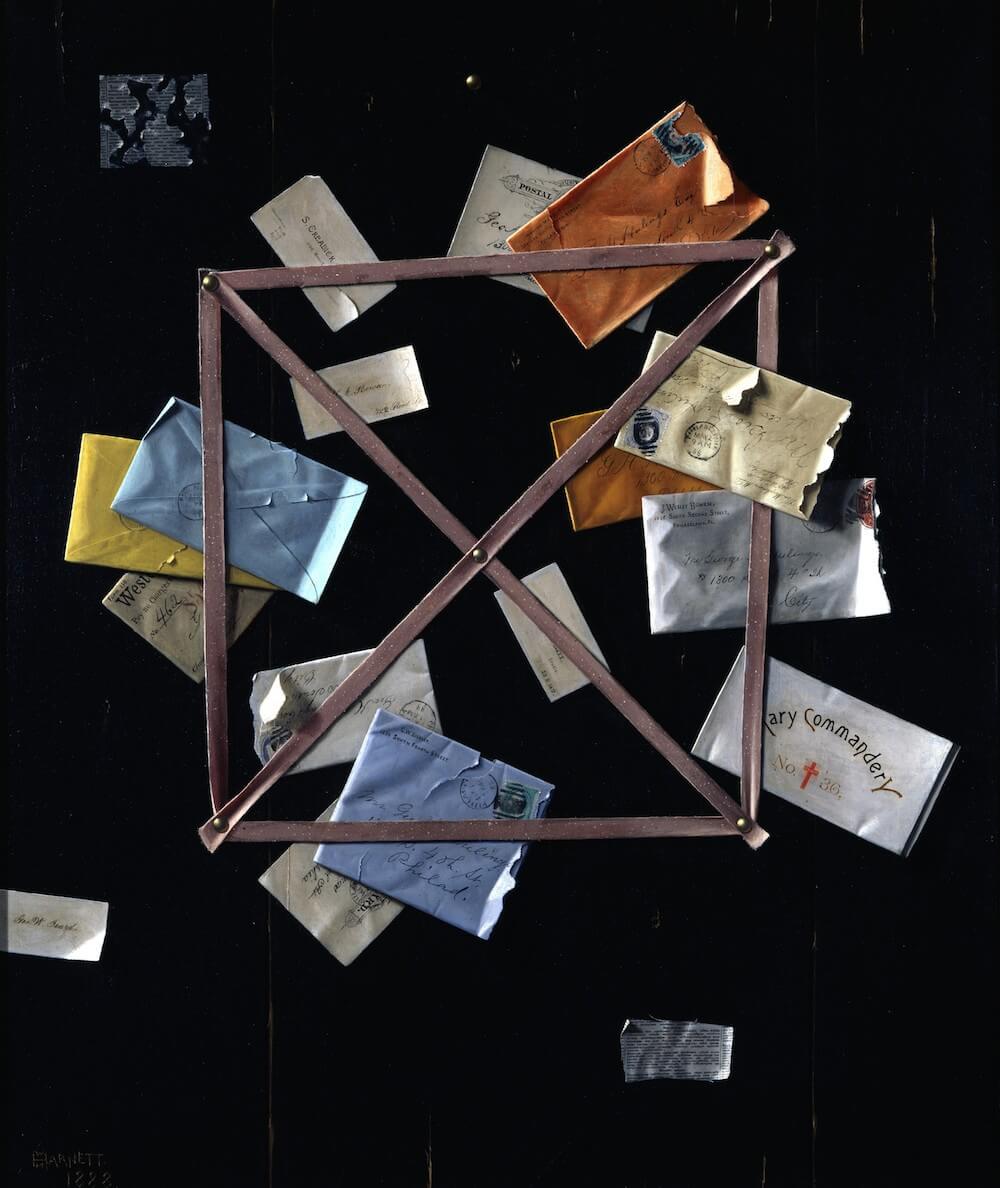

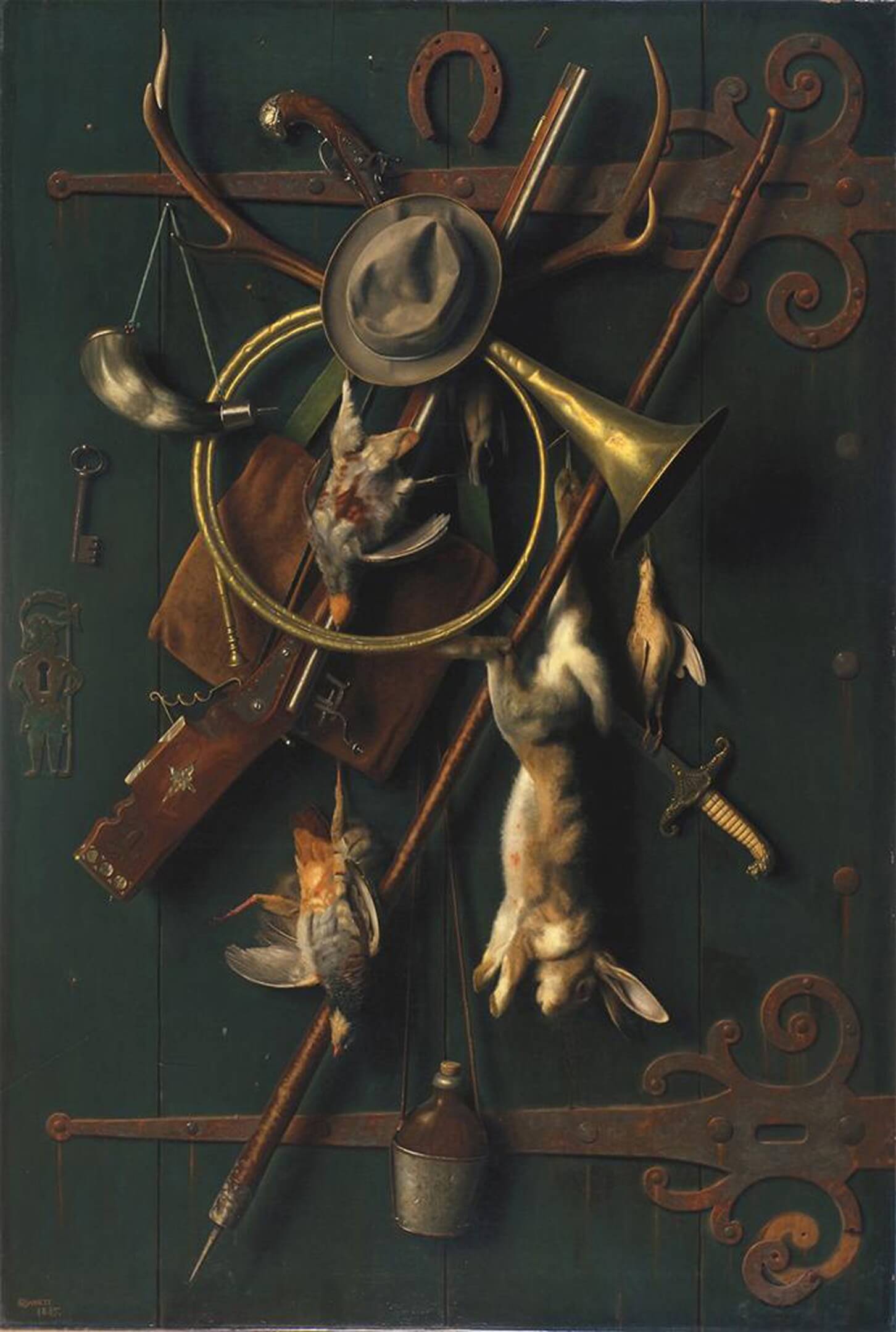

It was such a culture that gave us William Michael Harnett’s After the Hunt (1885), a hyperrealist depiction of dead game hanging alongside the instruments of their demise: hunting bugle, rifle, powder horn, hat, water jug, etc. It’s an impressive work, but imagining it hanging alongside contemporary French painting at the Paris Salon—for which it was painted—one is not surprised to learn that the reaction to the painting was chilly. It must have been regarded as a curious anachronism indeed. Upon its return home, the painting found a more appreciative audience after being purchased for display in a lower Manhattan saloon. Its story is instructive. Over a century after the colonial painter John Singleton Copley shipped his work to London to curry the favor of its Royal Academicians, American painters were still trying to prove their chops in the cultural capitals of Europe.

So were we always a step off beat: describing, indulging, and discerning yet never arriving at a fully mature visual art form? Our literature at this time was leaps and bounds ahead. “Moby- Dick” was a contemporary of Roesen’s Flower Still Life with Bird’s Nest. To Melville, the exhaustive descriptions of marine life that characterize the novel were never meant to stand alone. In cataloguing all known facts and legends of the whale, recounting all descriptions of whales in literature and depictions of whales in visual art, and in describing whaling as he had experienced it before the mast, not once does he miss an opportunity to tie his observations back to the habits of men. It is here that the imperatives of the naturalist and the magician are wed, in an art for which the acute description of a Latrobe is but a building block of a larger existential narrative. Hence Ahab, on the deck of his ship, reveling in the “linked analogies” of man and nature when his mate sights a ripple of breeze on the water.

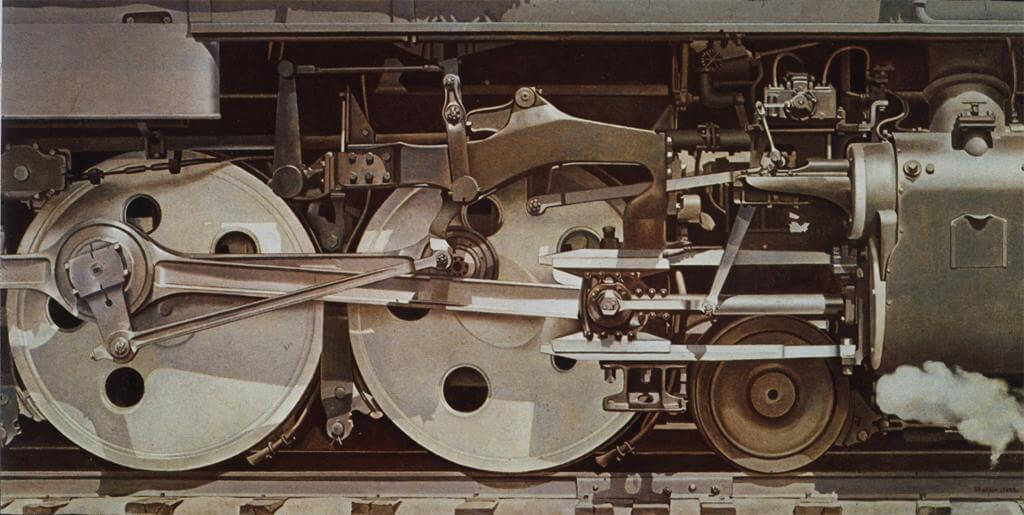

“Animating,” the final section of the exhibition, covers the first half of the 20th century, in which the wave of European modernism reached American shores and changed our imperatives once again. The thrust of this part of the exhibition is to demonstrate how artists absorbed and responded to the mechanical age, illustrated more literally by some (Charles Sheeler, Rolling Power (1939)) than by others (Patrick Henry Bruce, Stuart Davis).

Of greater interest than these, however, is a picture by Georgia O’Keeffe, From the Faraway, Nearby (Deer’s Horns, Near Cameron)(1937), which depicts a deer’s sun-bleached skull and antlers floating in front of a distant mountain range. The most powerful and poetic image in the show, it hums with a symbolic charge. If, by dint of an absolute faithfulness to nature, Audubon convinces us of the viciousness of a snarling marten, O’Keeffe has us believing just as strongly that she found her subject as she painted it, levitating above the desert floor. In Latrobe’s hands, such antlers might be rendered clinically against a stark white ground. In Harnett’s, they would be but a prop in a highly orchestrated mise en scène. For O’Keeffe, they are part of a place, inseparable from and meaningless without the context in which she paints them. It is this relationship of object to space that is unseen elsewhere in the exhibition, and it points to what has been missing all along. The painting opens a window into that truly great genre of American painting, the landscape, allowing light and air into the exhibition for the first time.

O’Keeffe’s painting points us back to where the show begins, with questions of how American identity has manifested itself in our visual culture. The uniquely American theme of place, as evidenced in all our great literature, and much of our popular music and film, is largely precluded by the formal structures of the still-life. Full of natural elements, our still-lifes are above all characterized by their very un-naturalness. From the clinical isolation of Latrobe’s rattlesnake to the contrived illusionism of Roesen’s flowers, the most earnest efforts toward realism in our still-life painting seem to have pushed us further from a truthful engagement with nature.

It is O’Keeffe’s painting that reminds us of the American landscape, our biggest, most reliable and most fitting muse. So did we have a Chardin? No, but we had O’Keeffe, and Marsden Hartley, and Church and Cole and Bierstadt, and a list of pioneering landscape painters that defined our country from its very beginnings. In the end, the greatest value of this fascinating show might be a reminder that place, not things, has always defined us as a nation, and that engagement with that great theme has given us much of our lasting and most important art.