Art at Kings Oaks

Newtown, PA

October 4 – 20, 2024

Located near Newtown, PA, just two hours from New York and an hour from Philadelphia, Art at Kings Oaks offers an experience a world away from the art fairs, big box galleries, and the endless scroll of tiny images on Instagram. Curated by Alex Cohen and Clara Weishahn, the exhibition, which features painting, sculpture, ceramics, as well as musical performances and classes, is installed in an 1839 stone barn, chapel, and the surrounding buildings, gardens, and landscape of an historic farm. Cohen and Weishahn have reimagined these unique spaces as a setting for visual and live arts events that harkens back to an era where the viewing of art was distinctly physical and inextricable from the local and communal. For this, the 9th installment of Art at Kings Oaks, Cohen and Weishahn have assembled an exhibition of works by 27 artists from 10 countries. They graciously agreed to share their thoughts on the show with Painters’ Table.

Painters’ Table (PT): Art at Kings Oaks was started in 2012. How has the exhibition and the event changed over the years? What are you most excited about for this year’s edition?

Alex Cohen: The first Art at Kings Oaks exhibition came out of a conversation with my friend, painter Derek Bernstein. Several gallery opportunities had dried up and we were considering the ingredients that made for inspiring exhibitions. Along with our friend, wood sculptor Matthew Merwin, we began to clean out the 1839 bank barn at Kings Oaks, the farm where my family has lived since the late 60’s. It was filled to capacity with farm equipment, ephemera, and junk. When the space was finally revealed, I recall the shock of raising a boom of lights into the air and first illuminating the incredible stone walls.

The whole process was so raw, thrilling all the way through. Our attendees reflected back the enthusiasm and what was only meant to be a one-off show continued and expanded. Each year built upon the last and a relationship with the space evolved. We began to display work also in a small stone chapel nearby on the property. The chapel was constructed in the late 19-teens/1920’s on the foundations of a late-1700’s stone barn. Soon after Clara and I met, she brought her background from working in the theater to curating and producing the exhibition with me. What began as an intimate, local endeavor now presents work by up to 28 artists from around the world. This fall marks our 9th iteration of the event.

Each Art at Kings Oaks exhibition is a major commitment for Clara and I. The project escalates over the nine-ish months of its production until toward the end we are completely subsumed by it. When the exhibition closes, we try to put everything to rest and return to our other pursuits. We happily continue to develop the relationships and knowledge we gain from the exhibitions but the project essentially goes dormant. This has been a critical part of the recipe, providing a buffer wherein we can dream anew. Building it more or less from scratch each time, revisiting all the necessary choices with curiosity for other solutions staves off habitual ruts and gives us room to reinvent or redirect.

Rather than just choosing another grouping of interesting artists for each exhibition, we think at length about what kind of feelings we want to cultivate and what new opportunities we want to embark upon… what expectations we can subvert, for ourselves and others. The successes and failings of each exhibition let us see a little further ahead and find the leading edge of our capabilities. I often think about it as a series of doors that are revealed with each subsequent endeavor, and through whose keyhole I am always trying to peep through.

One of the most rewarding aspects of these exhibitions is the relationships we develop with those who have lent their time and talent to building them. This collective effort is almost sacred and we have leaned into the natural cultivation of those group initiatives. So we are particularly happy and grateful to have worked this year with an incredible team of part-time assistants, builders, creators, volunteers, cooks, and event-makers. With each show it feels like our family grows and we try to weave that cultural capital back into the fabric of the project.

In addition to applying the lens of theater to how we create Kings Oaks events, Clara has developed remarkable horticultural skills in recent years that have been keenly applicable to how we organize, nurture, and ‘bring in the harvest’ from our projects. Gardening at its essence grapples with how to perpetuate and manage growth and decay. The endeavor of curating can well be guided by similar knowhow.

Clara Weishahn: Speaking to Alex’s mention of horticulture, I’m particularly excited about showing work this year that directly connects these two big aspects of our lives and interests: art and nature. Massachusetts ceramic sculptor Karlene Jean Kantner’s ornate hand-built vases and potato pots (she actually grew potatoes in these sculptural containers this summer!) are displayed throughout three spaces here: the chapel, barn, and garden. So visitors are invited not only into the historic buildings we have gently converted into galleries, but also our ornamental and vegetable-plot family garden right adjacent the barn, which overlooks the fields and woods. The late-blooming flowers are at their peak while the exhibition is open and everything is abuzz with pollinators and birds.

I work as a floral designer and grow cut flowers, so showing Karlene’s work has been extra meaningful–getting to arrange in her vessels. She is also teaming up to teach here on October 19 with a wonderful teacher, landscape designer, and gardener, Jennifer Walker, whom I met while studying horticulture at the Barnes Arboretum in Merion, Pennsylvania. Karlene and Jennifer are creating a very thoughtful retreat-like experience that invites artists and gardeners to slow down and consider time as their collaborator in natural and studio processes. Participants will be guided through observational, writing, hands-on, and interactive activities throughout the exhibition and green spaces at Kings Oaks.

I am also very excited about showing New Yorker Shari Mendelson’s incredible repurposed plastic sculptures in the chapel. We became familiar with Shari’s work last year and were immediately captivated by her incredible transformation of materials and the resonance of her objects with ancient art, which we are both very drawn to. We started envisioning an illuminated wall of glowing niches for her pieces and thanks to a terrific carpenter and a team of dedicated helpers we were able to create this very unique custom-made display. We have been getting more and more curious in recent years about creating ‘installation visions’ within the exhibition overall.

PT: Last winter the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) abruptly announced it would be closing its degree-granting programs after the 2024-25 academic year – an unexpected announcement that shocked the arts community. This year’s Art at Kings Oaks will feature an installation of recent PAFA alumni. How do you see the role exhibitions like Art at Kings Oaks might play in filling a void left not only by disappearing academic institutions, but also by increasingly common gallery closures?

Alex: I think a fatal flaw disrupting the legacy of these cultural institutions is a prioritization of career building and/or commercial success, which of course is in response to cultural and practical pressures. But that sort of expectation on outcome and the competition it engenders is really at odds with the merits of artistic education. It makes failure untenable, whereas these should be places that invite the risk of failure, buoyed by a sincere cultivation of community—which is to say, camaraderie. When I went to the Academy I experienced the transition from a small funky space to a massive depersonalized space. Where the old building had creaking floors and the constant intersection of pathways, the new space was oppressed by the drone of a massive HVAC system, and halls that dispersed the flow of artists. There was a sense of growing dissonance between the fertile life of developing artists and the evolution of the school’s identity.

Clara and I perceived a very vital young community that was forming among recent PAFA students, diverse in their talents and mutually supportive. It was heartbreaking to see the mismanagement of these schools threatening to end the legacy of what brought new artists into this community. We wanted to not only showcase the emergent talent of these young artists but to create an experience where they could participate in the creative process. We invited three recent graduates, Tali Burry-Schnepp, Ana Neifeld, and Henry Murphy, to build a space within the barn in which their work would be featured––an exhibition nested within the exhibition. It was not an easy process but the results of their commitment to art and to each other were so moving that it has furnished the exhibition with a very unique flavor.

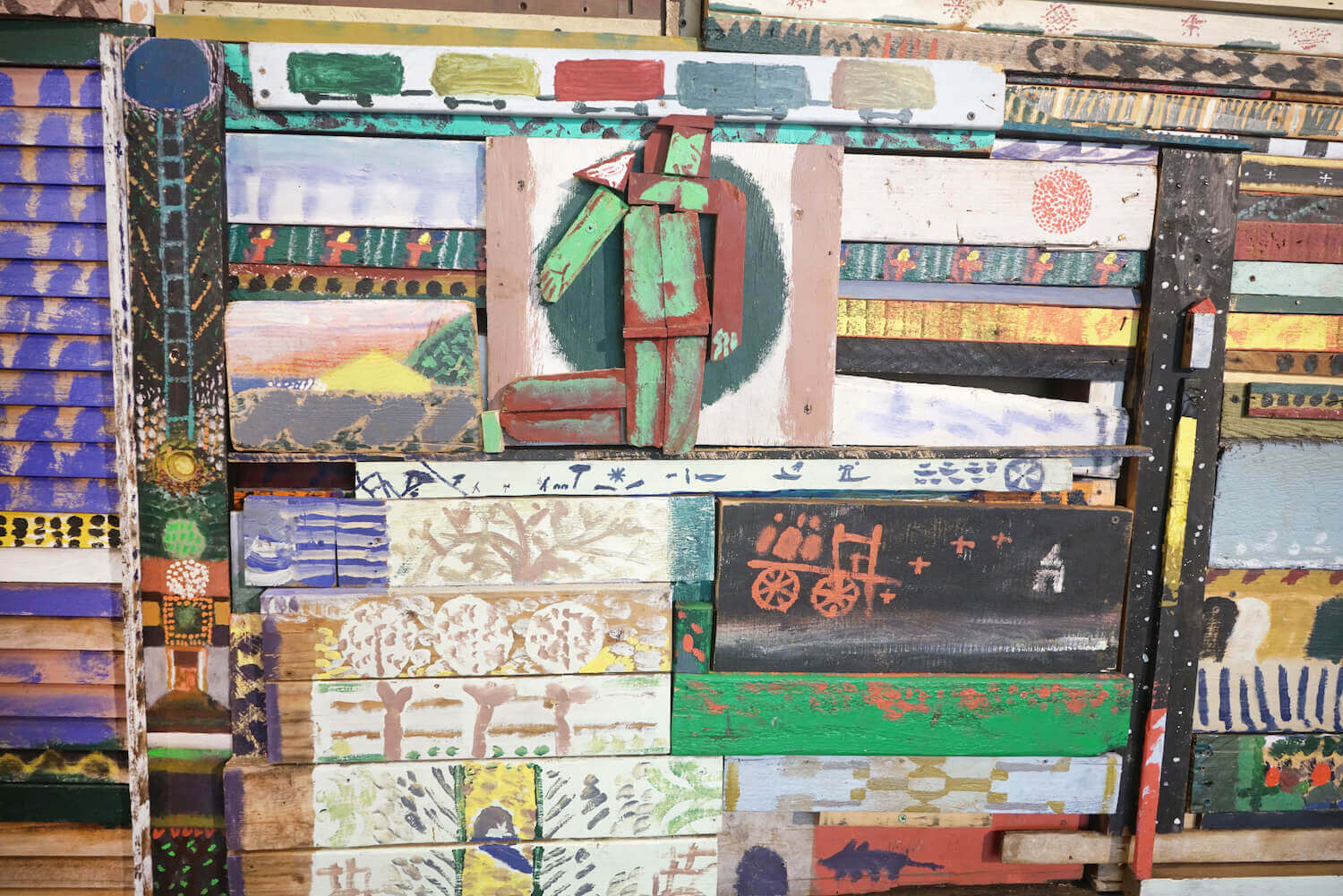

Clara: The trio has created an intricate wall composed of many painted pieces of found-wood, assembled into a collage or mosaic of sorts that defines the space beneath the central loft in the barn, forming an inviting room that was never there before. They created the painted elements throughout the summer in their backyards and studios in Philadelphia, New York, and here on the farm where they stayed in residence for a number of multi-day installation and creation phases, a process funded by ourselves and considerate donors. Above the decorative wall, a rough-hewn angel, carved by Ana Neifeld out of a fallen apple tree from our orchard, looks down on visitors, flanked by decorative symbolic flags. Beneath the loft, Alex and I installed their work — paintings, prints, ceramics, and textiles.

The day I asked Ana, Henry, and Tali to send me a title for their installation I was deep in the painstaking process of making labels for the over 360 pieces in the exhibition. Their answer stopped me in my tracks. Tribute to the Artist and Their Family. How powerful that these young artists have created something so beautifully unique to them and in tribute to someone who is so often misunderstood or undervalued. Not only a Tribute to the Artist, but to their Family. It makes me think about how we can’t do this alone. Even studio artists need community and connection. We need our Families, given or found. It’s very deep. And I’m happy to be part of that.

PT: Over the last fifteen years or so, social media has democratized art viewing by allowing anyone anywhere to follow and connect with work being made in art centers like New York. You’re doing something different, bringing the actual physical art – work by 27 artists from 10 countries – to be viewed in person. It’s difficult to organize and put on an exhibition of this size! Could you talk about the value of in person viewing, what it means to you, and what it brings to the community?

Alex: The landscape of social media has undeniably been a double-edged sword that has brought us into contact with myriad creators while absorbing our attention into a sedentary scroll. As you say, it is marvelously democratic and to a large degree takes down the typical borders and gateways to artists. You can let your eyes roam far and wide to discover artists regardless of where they are in their “career” or on the globe. Of course, the social media map is fairly recent and one can forget that there are many extraordinary artists beyond its edges that ought not be overlooked for lack of tech-savvy. So while we do indulge heavily in the endless scroll for artists we take care to be looking elsewhere as well.

The digital landscape is convenient and efficient which feeds a very rational part of the brain. But the greater value of art, of course, lies in its irrational and unfamiliar qualities––things found in the periphery of consciousness. Viewing art online is direct and contained, with no periphery. Zoom meetings can be so exhausting because one doesn’t feel permitted to look away. But art is often more effective when you look away. When it lives in your mind as well as before your eyes. An in-person exhibition allows space for the viewer, with all of their tangential awareness and inner relationships. This advantages all the qualities of presentation; the staging, pacing, proportion and proximity. It includes the anticipation; the drive to get to a place as well as the departure, where one digests what they have experienced. And even the smell of the artwork should not be undervalued as part of being in its proximity.

The barn, chapel, and now garden where we exhibit work are relatively short distances apart but I think it’s crucial that one has these intermissions while they walk from one space to the other and get to enjoy the natural setting as well. The other day we watched a couple, who had just spent a long while in the exhibition, just sitting in chairs outside of the barn and sunbathing. These are things that allow art to be properly absorbed and considered. The instagram format gives immediate access but, just as immediately, one image is replaced by another and it’s hard to have an experience that can alter you.

It is peculiar that we refer to online platforms as social media where there is a complete absence of the physical experience of society. We are thrilled that Art at Kings Oaks has had such a lively communal element to it–– seeing friends and family share time in the spaces; artists meeting for the first time. We spend so much time planning and thinking about the exhibition in advance that it’s a delight to see our efforts animated in space by the bodies moving in relation to it.

The international aspect of the exhibition has been a particular joy. It is a way of manifesting some of the more fascinating angles of social media, which has formed a global community. There is an aspect to the metaphysical worlds of art that always feels foreign and is attractive as such. So bringing work from literally foreign places doubly tickles the curious mind.

Clara: We are always excited to discover an artist off the beaten path whose work speaks to us. We’ve shown some artists who don’t use the internet and only communicate by telephone or letter. We often show artists from all different stages of life–people in their 20’s to their 80’s–which inevitably invites many different modes of communication and connection. Some artists are difficult to reach due to logistical or language barriers. This year we were only able to contact an elusive artist in Japan who is creating mysterious, almost talismanic paintings and objects, San Gertz Nigel Nina Ricci, through another Japanese artist, Hayato Kumagai, whose cut-paper creatures are roaming across the walls of a granary in the barn.

The physical aspect of mounting an in-person international exhibition can be daunting indeed. A Ukrainian artist, Stepan Budulak, shipped two small bronzes to us that sadly were never released from Ukrainian customs. Thankfully we did receive his two wooden sculptures. We spent months working with a very kind gallerist, attempting to bring paintings from Moldova by a painter we admire. The process ultimately wasn’t feasible, but we almost managed to set up an art-courier situation with a relative who was in Moldova over the summer. Another friend considered bringing three delicately rendered paintings by Nuttanich Ruadrew from Thailand in his suitcase. But it turned out that the Thai postal system was much more efficient and affordable than we had anticipated. Happily, we were able to connect Maine painter Jarid del Deo with a friend who was passing through and she brought his landscapes down to us this summer. And Lani Irwin’s self-portrait was brought on a plane from Assisi by a friend. We have dozens of similar stories.

Sorting out how work is shipped or transported is inevitably a key aspect of how we build the exhibition. We get to know our artists, problem-solve with them, and share the cost and risk of moving objects over long distances. When artists can’t afford shipping we offset their costs and we fundraise for that. When you show with us, you are really invited on a personal journey and the artists engage on all levels, as they are able or feel comfortable.

Also because of such a large international contingent this year, Alex personally took on framing over 60 works for display, many works on paper and paintings too. Artistically it was worth it to us to show the work at its best, protected and honorably presented on our walls, but the costs and labor are enormous. These are the kinds of decisions we weigh every time we do this project.

In a big way, this exhibition exists because these spaces beg the question “what could happen here?” And we are inclined to keep responding to that question. So even when the process can feel grueling or unrelenting in its pressures, we still feel very lucky to have the opportunity to throw our energies into this project–to make something that means a lot to us and to those who make contact with it.

PT: Kings Oaks features visual art installed in a historic barn and chapel, fantastic architectural spaces but both quite different from the white cube commercial galleries. What are the challenges of hanging a show in these spaces, and what are some of the rewards?

Alex: The places that art comes from are hardly uniform. Studios are diverse, reflecting the nature of the artist’s mind and proclivities. Yet we have become accustomed to a certain uniformity in presentation. There are very practical reasons for the white-walled gallery which lets the singular flavor of the artwork come forward without complicating its context. This aesthetic suggests that it is clarifying, sobering, and above all respectful. Yet the lived experience of that context for me is often a deadening of the artwork. Many galleries can even feel hostile in their blankness and the artwork looks like it’s waiting in a terminal for a flight. I am often longing for a sense of place, for signs of life. Much of what I adore in art is a transcendence and an endurance of time. The ephemerality of exhibitions is lovely too, but not when art is treated as fashion with an expiration date.

We are fascinated to see how people live with their art, to see how it plays a vital role in their domestic life. In the classical world one often finds a seamlessness in the visual space between the artistic aspects and those of “daily life”. I love when art appears at once integral to the visual flow of a space and yet has one foot in another world, as with a Roman fresco or Burmese shrine, for instance.

We are very lucky to have these spaces on the farm in which to experiment with presenting artwork and concerts.

Of course the demands of these spaces and the surprises we are met with take a surplus of attention and granular problem solving, but that too builds an intimacy for the exhibition. We used to hang the work on wires that dangled down twenty-some feet from the top of the barn wall. This required us to get on a ladder every time we needed to adjust a painting even slightly. We have recently built toned plaster-paint walls with barnwood framing to integrate them into the space. This gives us greater ease in hanging and a gentler visual backdrop for the work. This was an interesting shift for us—adding to the spaces while trying to keep the visual vocabulary consistent.

Clara: There are inevitably challenging aspects to working in these spaces. They are protected from the elements but are not climate controlled. We are very careful to communicate this clearly to our artists. And we hold the event in autumn when the weather is traditionally moderate. We also keep the exhibition duration limited to around three weeks from preview to closing. This brevity cultivates a wonderful festival atmosphere and close to 1,000 people come through. It’s energetic and ephemeral, living on brightly in collective memory. Maybe because of my theater background, where you work for months or years to create something that may only exist for several weeks in front of a live audience, I’m comfortable with the timeline of our project.

PT: Often painting is shown in isolation from the other arts, but the Art at Kings Oaks exhibition features painting, sculpture, ceramics, as well as musical performances and classes. How do you think about the interplay between visual art, performance, and community activities?

Alex: Art carries with it the solipsism of its media, which seems to amplify in the company of like media––and that can be a wonderful concentration, but there are many universal qualities that are released by the co-mingling of different artforms. Paintings have an object-ness, concerts are pictorial, functional crafts have abstract intrigues. Curating this multiplicity of things and experiences tends to have an animating quality, and animation points in a forward direction. So there is a feeling of our projects going somewhere. I like the ability to see and play with the tension between juxtaposed media or experiences. You can find rhythm and create moments of intensity and moments of release.

Clara: I grew up very rurally in Alaska, outside of a small town called Haines which is incredibly beautiful and remote. I was always drawing and reading and had a pretty internal, private life as a kid. But I was secretly drawn to theater and music. In my teens an opera company from Juneau came to my home town to perform a production of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly in English. I was struck by how opera contains so many art forms in one–costumes, set and lighting design, movement, music, narrative. I was hooked. I ended up studying with the lead soprano who ran the company and subsequently had many experiences with music and theater that led me to where I am now.

On some level Alex and I share a longing for what he calls the “three-ring circus,” where one art form feeds into another or they can occur concurrently and mingle. It was only a matter of time before we would bring live arts to Kings Oaks. Then we had the incredible opportunity to host concerts in 2022 and 2023 by Philadelphia’s Grammy-award winning choir The Crossing. Since then, we have been hosting visiting musicians and composers who come to Kings Oaks to make videos with an excellent film production company called Four/Ten Media. Some of them stay here and offer an intimate concert at Kings Oaks or nearby. Some of our most beloved musical heroes such as the Norwegian-Swedish choral ensemble Trio Mediæval and composer/performer Caroline Shaw and Sō Percussion have been here. It’s a dream come true.

These events happen literally out of our home and everyone we work with is invited to engage on that level of intimacy. We plan and curate everything on a case-by-case basis. Can we take time away from our personal projects and jobs for the amount of time we need to make the project happen and be satisfying? The exhibition takes around nine months from start to finish. During the final three months we are both essentially working around the clock nearly every day of the week. Recently, Alex and I decided to adopt a biennial model going forward to give ourselves some breathing room and incubation time, and to make space for other projects. I admire the cycle of biennial plants. They grow an unassuming basal rosette of leaves in their first season, go dormant over the winter, then send out a dramatic spike of bloom the following summer. It’s worth waiting for.