Sam Cornish, editor of Abstract Critical, the UK based website dedicated to abstract painting and sculpture, recently posted that the site will stop publication. This is sad news to anyone interested in abstract painting and sculpture. Since January 2011 the site has published thoughtful, long-form reviews, opinion pieces, and videos.

While quality content is crucial to the success of any site, a regular publishing cadence is also important. Abstract Critical had both, a fact which made me and many others regular visitors. While commenting has been integral to blogs since their inception, Abstract Critical cultivated an atmosphere conducive to debate. While they may not quite have achieved a Cedar Bar of the internet, they succeeded more than most blogs in fomenting discussion of all sorts, from the bitingly critical to friendly banter exchanged amongst frequent commenters.

Sam Cornish and Robin Greenwood are to be particularly commended for their efforts to make Abstract Critical a vital source of criticism and discussion around the topic of abstraction. Not only did both contribute a significant amount of writing to the site, but their efforts to spur conversation around the articles (no small task) was and is greatly appreciated.

Although no new content will be added, existing articles will remain online. The Abstract Critical Twitter account will also remain active and The Brancaster Chronicles, an ongoing series of transcribed studio visits, will also continue to be published as a new site.

Cornish’s last post to Abstract Critical featured some of his favorite articles from the site. Since Painters’ Table has featured many pieces from Abstract Critical I thought I would contribute fifteen recommendations of my own. This selection only scratches the surface of what is available at Abstract Critical, but any of the articles below constitutes an excellent launch point for perusing this resource.

Best wishes to the Abstract Critical team and thanks for a job well done.

What Paint Does

Robin Greenwood considers the dual (and competing) roles of paint as both a material and as a “designator and articulator of form and space.”

Brancaster Chronicle No. 10: Anne Smart Paintings

A group studio visit with painter Anne Smart: Sam Cornish comments that several of Smart’s paintigns “seem to have … almost a natural light. There is a sense, not of a representational painting, but of light that you might experience.”

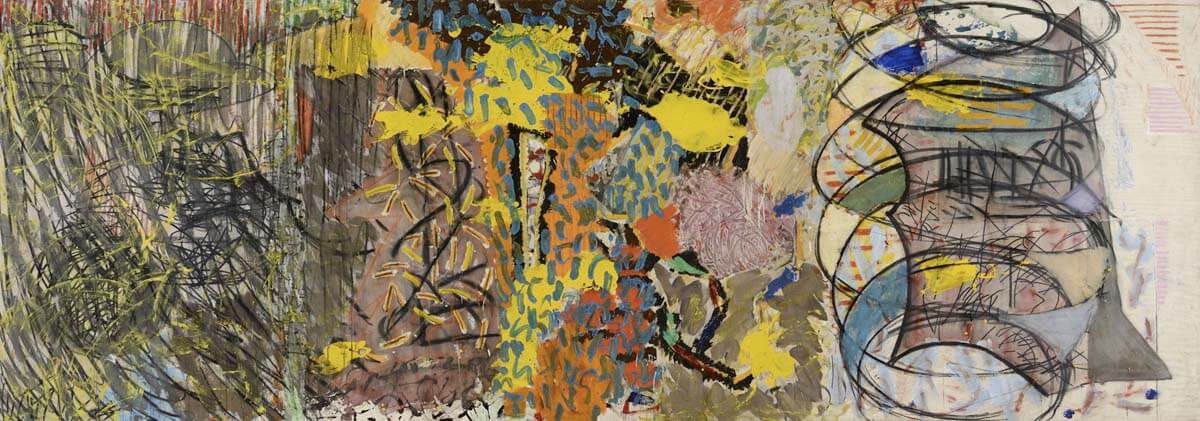

Joan Mitchell, The Last Paintings, A Tribute

Gary Wragg reflects on the late paintings of Joan Mitchell. For Wragg, Mitchell’s last paintings express “a feel of an embrace and exuberance, a generosity and love of the outdoors, of air, light and being enveloped…”

The Social Art of Paul Klee

Reviewing Paul Klee: Making Visible at Tate Modern, Ben Wiedel-Kaufman notes that Klee “developed a searching engagement with the world – in its social, material, mythological, expressive and private manifestations – alongside a radical approach to the formal elements of picture making. It is a fusion that seems worth rescuing from both formalist and Marxist accounts.”

Turner & Frankenthaler: Making Painting

Emyr Williams reviews the exhibition Making Painting: Helen Frankenthaler and JMW Turner at Turner Contemporary, Margate writing: “The two artists are represented by paintings and watercolours. In fact, water is one clear link between them: the way it carries colour, extending its reach into the corners, lapping against the edges, the bleeding and flowing of pigmented washes, suggestive of form or simply evocative of place as felt experience.”

Iconophilia

Mark Stone argues that the image and the being it communicates is missing in contemporary abstract painting: “…we abstract painters have been more concerned about eradicating visual confrontation with being/images. We are more comfortable with warped re-presentations of style. We prefer the documentation of our painting processes over the depiction of visual things.”

Frank Bowling Interview

In a video interview, Robin Greenwood talks to painter Frank Bowling about his life and his work. Bowling remarks: “What we inherited from the first generation [of abstract expressionists] was the freedom to apply the paint in any which way you want, pouring it, spilling it, dripping it … It was a kind of exhilarating thing.”

The Influences of Manet

Painter Alan Gouk muses on the ways Manet has influenced later painters. Gouk concludes: “Manet emphasises that the continuity of painting, the continuity of value in life, is made apparent if the artist finds and holds on to his own mode of vision, trusting his own eyesight and his ‘convictions of taste,’ influenced as they inevitably will be by the passing show, and the march of ‘history’.”

Gillian Ayres: Paintings from the 50s

Robin Greenwood writes about a 2012 exhibition of paintings by Gillian Ayres. He notes: “One of the things that struck me looking at these paintings is how little they make one aware of a picture plane; how very unflat they are; how very un-graphic in every sense; and yet, how true to the integrity of the painted surface. The spaces herein are not wrought out of illusionistic ambiguities, but from plastic certainties.”

The Ruthless Matisse

Patrick Jones reflects on Matisse: In Search of True Painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The biggest surprise for this painter from the Matisse show were the surfaces of the paintings. They were amazingly distressed, with cracking, scratching, gouging and much obvious changes of form… Matisse was always possessed of a remarkable raison d’être, was engaged in meaningful and purposeful action over many decades, dispelling any reputation as a nervous ditherer.”

Improvisation in Abstraction

Robert Linsley explores the idea of improvisation in relation to abstract painting. Linsley writes: “Improvisation does not mean pulling art out of thin air. It is a congerie of techniques that enable the possibility that the new will appear… Improvisation is more akin to normal living than it is to flights of virtuoso artistic skill. And yet, great improvisers usually are virtuosos, it’s just that they have set their own standards of skill. It turns out that skills are best learned in the act of creation.”

Sophia Starling: Interview

Interview with painter Sophia Starling who remarks: “I became interested in what abstract painting could be, so I developed this process where the support, the paint and the material all have equal weight, they are all as important as each other. Most painters use the support and material to create a surface on which they will create their painting; whereas I wanted the material, the structure and the support to make up the composition of the painting.”

In the Studio With… Vincent Hawkins

Video studio visit with painter Vincent Hawkins where the artist discusses his recent works on “cardboard and oval-shaped supports.” Hawkins notes his interest in “releasing some of the forms out of the constriction of the edge and trying to release it into the environment rather than containing it within the edge of the format of the the rectilinear surface… I also wanted to make something of very meager means…”

Gary Wragg: Positive Provisional

Sam Cornish considers the work of painter Gary Wragg in relation to provisional painting. Cornish writes that Wragg “avoids heroic, definitive or authoritative statements, who posits a vision of art which is as circular, or perhaps labyrinthine, as it is progressive. In all these senses he is provisional, almost with a capital P. Where Wragg differs – or at least the most crucial of the many ways in which he differs – from those artists gathered under Rubinstein’s rubric is in his evident and overriding belief in art, and in abstract art, as a place of meaningful and compelling visual experience.”

Richard Diebenkorn: A Door Opened

Ashley West writes about Richard Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park paintings. West recalls his first exposure to Diebenkorn’s paintings at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1991: “A door was opened and it dawned on me that here was an approach to painting that was both measured and free – on the one hand the geometric structure was alive, dynamic, felt, and on the other the freedom of brushwork and colour was intensified through containment. These paintings were rigorous in their abstraction and presence, while expressing a sublime feeling for landscape.”