I first met Trent Miller when he was my seat-mate on a plane traveling to Madrid in 2003. A group of painters, all Boston University MFA student and alumni, were planning to spend a week perusing the Prado, Reina Sofía, the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection, and the surrounding towns. During the course of the flight and the following week, Miller and I discussed common interests from poetry and the films of Tarkovsky to the great Spanish painters: Goya, Velasquez, El Greco, and Picasso. We have kept in touch sporadically over the last decade, a period in which Miller has continued to develop his highly-complex and personal vision through paintings and drawings in which the observed world and that of the imagination harmoniously coexist.

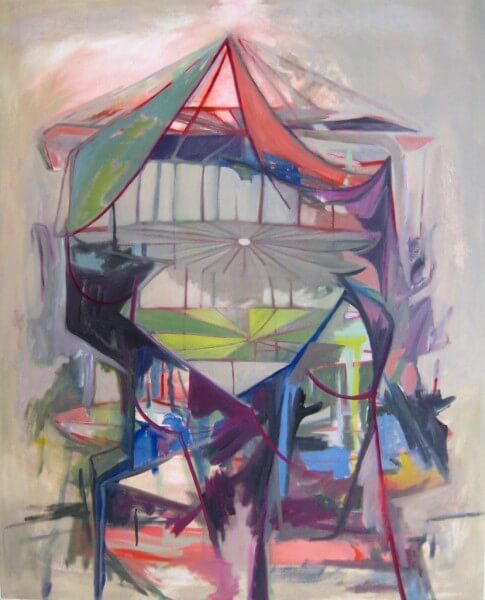

Miller’s paintings render the abstraction/observation divide irrelevant as one becomes convinced, looking at his paintings, the artist does not distinguish between the two. The two modes are equivalent, and the viewer may wander between them at will.

Miller recently agreed to share his thoughts on the last decade of painting and his new work, now on view in the exhibtion Trent Miller: Spindrift and Tether on view at James Watrous Gallery, Madison, Wisconsin through February 24, 2013.

Painters’ Table (PT): Many of the structures in your recent paintings feel specific, as if you were painting particular structures, rather than variations on a theme. The painted forms even feel like they inhabit specific spaces in specific locations. Do you paint from a real model, from your imagination, or do the structures in your paintings come out of the painting process?

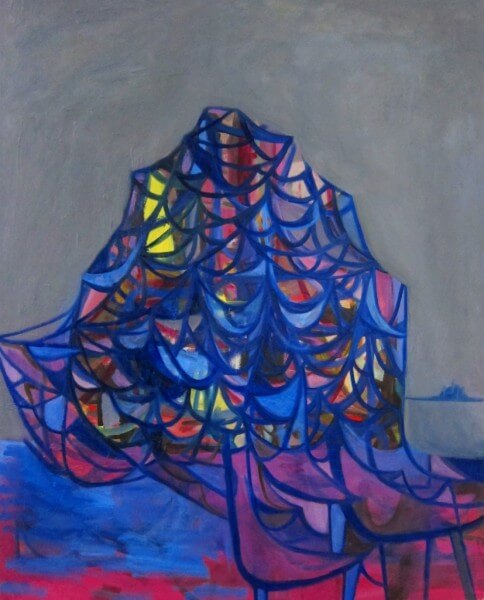

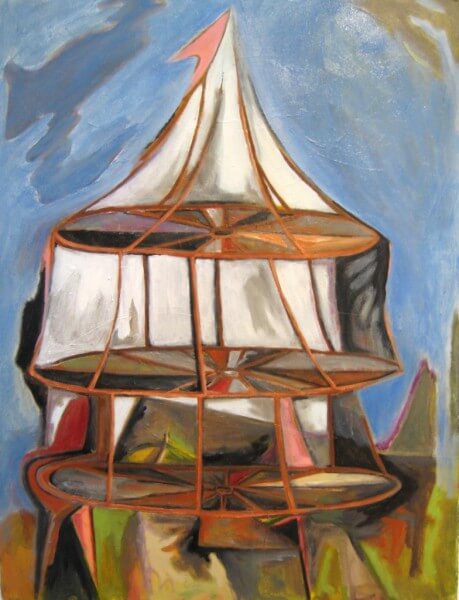

Trent Miller (TM): All of these paintings are coming from my imagination. I’ve been using this same tent/birdcage/scaffolding type structure for the past three years, and it continues to crop up during the painting process. The more I paint it, the more I see it around me in anything from birdcages to grain silos. I usually start with a field of color and then build layer after layer alternating between lines and larger areas of color. Over time, a particular structure with its own personality starts to take shape. I feel like each evolves into a very particular structure in a specific location, but the spaces and locations are completely imagined. This is what fascinates me: the ability to create an entirely new world in paint that references the world in which we live but in the end only exists on these canvases.

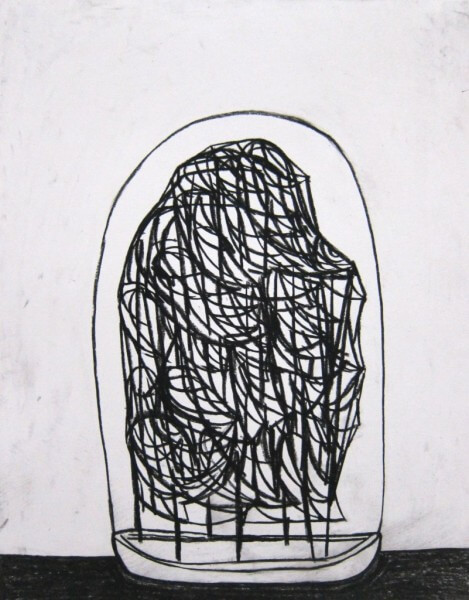

PT: Your drawings are often overtly figurative yet your recent paintings, however strong the implied figuration, are resolutely abstract. Can you talk a little about how your drawing and painting practices interrelate?

TM: I’ve been making these strange little (14”x11”) charcoal on paper drawings for the past fourteen years. For much of this time, they have been very representational—with figures, interiors and exteriors—although they have moved more toward complete abstraction at times. I always joke that when I draw, I’m like a guy in a cave with a stick. I just sit down and see what emerges on the page. The drawings tend to be more intimate than the paintings, with mysterious little narratives. Painting for me is a different thing: it’s a much slower process and maybe more like making a feature-length movie as opposed to taking a photo. In recent years, this longer process has continued to point me toward these resolutely abstract images. I’ve tried to force the drawings and paintings into each other, but this is always a mistake. Interestingly, the more I let go of trying to make them relate, the more they start to inform each other. The drawings start to have bits of abstract shapes and lines in them, and the paintings start to have more landscapes and nods to the figures in them. When you see them all together in a show, really interesting relationships start to emerge.

PT: Do you draw from paintings, or vice versa?

TM: I occasionally do tiny pen sketchbook drawings from paintings, but I don’t really do charcoal drawings from the paintings. I’ll also sometimes directly reference a charcoal drawing as I’m working on a painting, but it’s pretty rare. However, many of the images for the paintings and charcoal drawings start as tiny doodles on scraps of paper. I do a lot of these during meetings, while on the phone, or during other tasks when I can’t really think about what I’m drawing. It’s amazing what appears when you let your mind and hand wander in different directions.

PT: In a recent statement you declare a metaphorical solidarity with the self-taught artist Emery Blagdon, who made sculptures he called “Healing Machines.”

TM: I first saw Emery Blagdon’s work in a show at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin in 2008, and the experience was life-changing. When I walked into the room that contained everything Blagdon had ever made, it felt like a wave of energy hit me. The more I looked, the more transfixed I became. I walked out of that room in a bit of a daze, overwhelmed and thrilled by the mystery of Blagdon and the Healing Machine. I love the term “healing machine,” and I love the somewhat shamanistic idea of the power of the object for healing. (Note: Emery Blagdon: The Healing Machine is on view at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center through January 2014.)

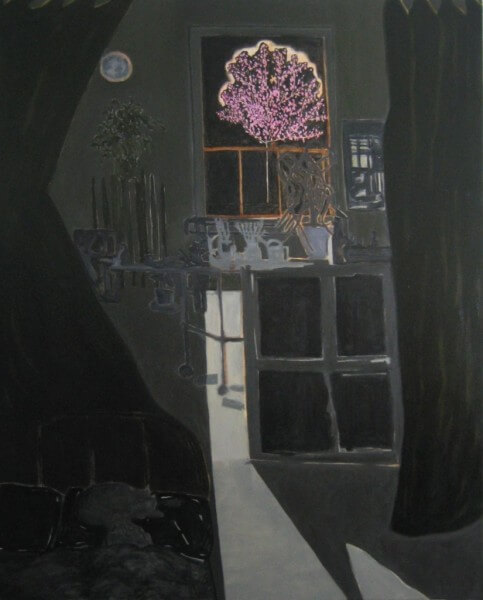

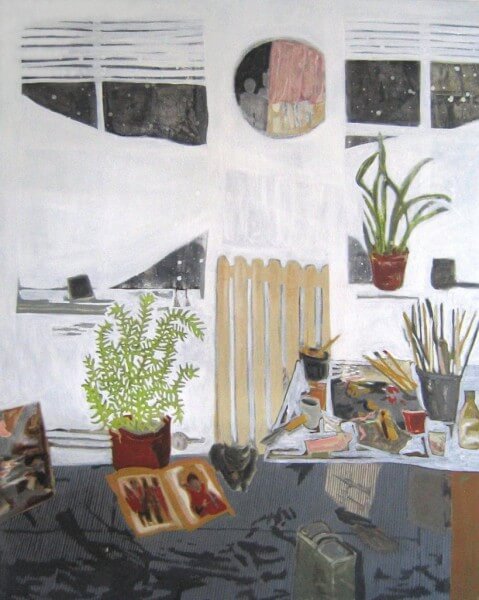

PT: There is a deep feeling of narrative in your work and yet a narrative never explicitly emerges. Interestingly, hundreds of narratives seem possible in any one of your paintings, from your earlier studio view paintings, like Novgorod Moon (2006) to more recent works such as Another New World (2011) and Dredgers and Drifters (2011).

TM: I love that there seem to be hundreds of narratives possible. I think It all boils down to the idea of mystery. I love the mystery of certain paintings, of certain movies, of certain songs. It’s the mystery that keeps it interesting to me. I’m not talking about work that is overly obtuse, rather work that feels like you can almost figure out the story, but something still feels a little off. The deeper you dig, the more questions you have. I’m drawn to pieces that have a particular mood but a very open-ended narrative. This is the kind of work that sticks in my head for years, and this is the kind of work that I hope to make.

PT: In 2011 you had an exhibition titled “Ten Years of Painting,” referring to the decade that had past since you came out of graduate school. Can you talk about this time a bit? In hindsight was it valuable to reflect on this period? Do you feel differently about your work moving into the next decade?

TM: Since finishing grad school in Boston, I’ve lived in Tivoli and Hudson, NY and now Madison, WI. Each geographic move shifted the work in a new direction. Some of this is the strain of the actual move and the settling back into a new studio and life. I’ve been in Madison for seven years now, and I’ve had my current studio in my backyard for five years.

I’m really glad I did the Ten Year show. In doing this, one of the biggest surprises for me was to find that things had actually changed less than I thought. I felt like some of the work was so different, but once it was all up I was pleased to see the similarities between the earlier studio view paintings and the more recent abstract paintings. The markmaking, the paint handling, the shapes were consistent throughout all the work. I was happy with how well some of the older work held up. It was also a nice way to draw a line and say “OK, I did that. Now what?”

Looking at the future is always a little strange because as soon as you set a course, something else pops up to send you in a new direction. I do really feel like the paintings are in control, and will give me new directions if I look hard enough. I see this new world of healing machines, water, and THEY as something that I can explore for many years.

Trent Miller: Spindrift and Tether is on view at James Watrous Gallery, Madison, Wisconsin through February 24, 2013.