Brenda Goodman: Paintings

John Davis Gallery, Hudson, New York

July 17 – August 10, 2014

In Brenda Goodman’s recent works, completed after her move from Manhattan to the Catskills, she continues to explore powerfully personal narratives animated by a visual language that moves that moves freely between abstraction and representation. On the occasion of her exhibition at John Davis Gallery in Hudson, New York, Goodman graciously agreed to discuss her recent work with Painters’ Table. — Brett Baker

Painters’ Table (PT): Equating the materiality of paint with that of the body has always been present in your work, but in several of your new works – such as Red Branch (2014) – painting and body seem united as never before in a metaphor of process. The life of the paint (its material journey) and the life of the body (also a material journey) become one.

Brenda Goodman (BG): An interesting observation. The thing is, I don’t make those kind of distinctions. Ever since I was a student over 50 years ago, I have been in love with oil paint and the sensualness of it. I have experimented throughout my whole career with various tools and additives to express my emotional life in the paint. Sometimes, for example, my self portraits are painted very thin and built up in thin veils of glazes and other times I felt they should be thick and raw. And that goes for my abstractions and my figure/abstract paintings as well. I love playing thin and thick, bold and subtle, off each other. But most important, this is not an intellectual process. I use the techniques and materials that FEEL right for any given painting. I guess I’m just one of those artists who puts it on and takes it off until it feels right. In the case of Red Branch, there was another painting that I didn’t like so I covered it with white. Because of the original painting, there was a ghost image in the white and I began to pull it out until the shape in the current painting emerged and the piece grew from there. That sort of intestinal shape goes way back to work I did in the 70’s but when it pops up in recent work, where other more recent shapes do as well, it always surprises and pleases me, because the thread of who I am is always there.

PT: Although your work as a whole has been categorized as expressionist, you’ve engaged with a surprising and inspiring range of stylistic approaches, as well as the entire abstract/figurative continuum. Can you talk about how your approach to a painting or a new group of paintings evolves?

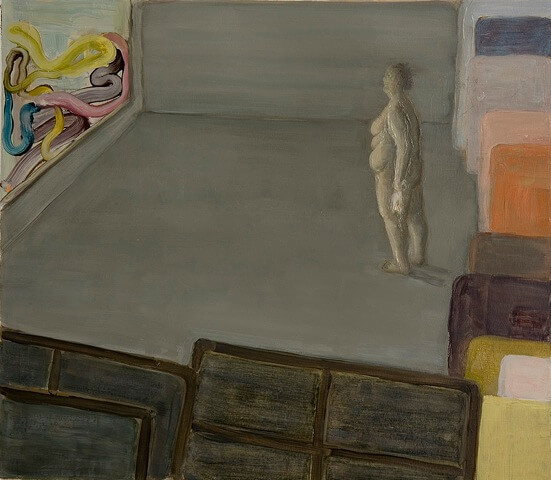

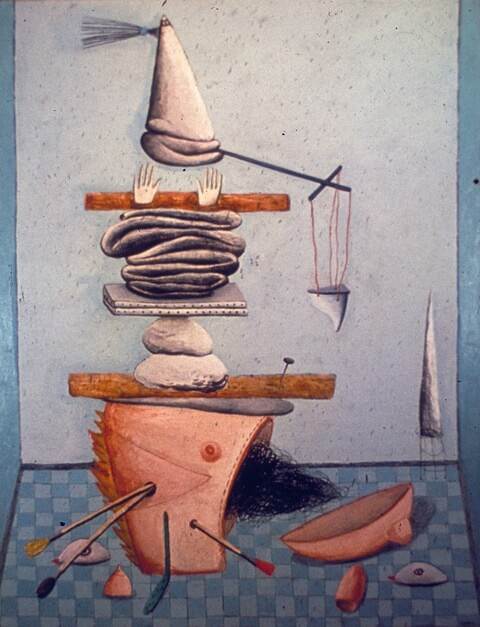

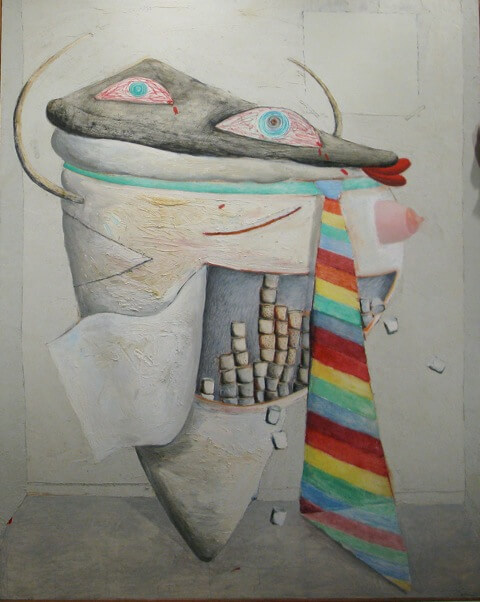

BG: My work almost always comes out of something that is going on in my life. In the 70’s I used symbols to express myself—they were usually abstracted shapes that represented someone or something to me and I would create a narrative around the symbols. I did that for many years but then wanted to let the work break open and not be as controlled so for the next several years I did large abstract paintings that I couldn’t fully explain but were very freeing. But then, after a while, I longed for that more personal emotional connection and in 1994 I began a series of self-portraits that expressed a negative feeling I had about my body. What was good is that some of the abstract elements of the previous work carried into the new self-portraits. This began my serious interest in combining abstraction and figuration. In 1995 I did a series called “A Song for My Mother,” where I finally felt I’d successfully integrated the figure and the abstract in my work. Then in 2004 I had a need to paint myself more naturalistically. Being very over weight, I found beauty in the forms but also I felt quite exposed and vulnerable. I also found a way to incorporate the canvases and stretchers in my studio as abstract elements in these paintings.

PT: Your previous group of paintings portrayed the figure inhabiting an interior space – often a self-portrait in the studio. Discussing those works in a 2007 interview, you talked about wanting your work to be very open about how personal experience and emotional content were presented. Your new vocabulary of forms is more abstract – bodies are now represented by parts of bodies – in many works the body is presented as an integrated image/action. What prompted this shift back towards abstraction and how did the experience of making overtly figurative works in recent years affect these new paintings?

BG: The new work is pushing the abstract and geometric more—suggesting the body rather than representing it. It’s all a continuum. I haven’t let go of anything. I’ve just added more elements, more challenges.

PT: Can you say a bit about scale? Some of the paintings in your current show at John Davis are very small – 6 x 8 inches. Are these examples of studies or are they conceived of as standalone works?

BG: Scale. I love playing with scale. Scale of elements within the paintings and scale of the individual paintings. Ever since I was a young artist I went back and forth between small, medium, and large paintings. And because I have done this for so long, the shift in scale is not hard. After finishing the large paintings for the show at John Davis, I began a series of small oil on paper pieces from 6 x 8 inches to 10 x 10 inches. A teacher told me a long time ago that there should be power in a small painting and intimacy in a large one. That was great advice.

PT: Painterly is a term most often associated with a general “love of paint” and primarily addresses painting as a positive force. Clearly your work is painterly and there’s an evident pleasure in the process of painting. Yet, it seems to me that your paintings don’t shy away from another aspect of painterly feeling – that painting can be a difficult, exhausting process for both body and mind. In your works this emotional duality feels present in the paint itself.

BG: It is certainly true that my work is painterly, in the sense of loving and exploring materiality of paint itself. But as I said before, I have always used this materiality as a way of expressing emotion, both personal and emotion related the reality of being human. My work often walks the line between humor and horror. Duality exists in almost all my work, even these newest paintings that are more upbeat than some of my earlier work—there is still that dark element lurking, Sometimes that dark element fills the whole painting and IS the painting which was the case 4 years ago when there was a tragic death in our family. But I needed to paint those feelings. It wasn’t hard or exhausting—it was sad and necessary to communicate. The only time painting is difficult and exhausting is when my will and ego are holding onto something in the painting that is blocking its completion. Then I have to let go and surrender, and once I do, the painting finishes itself. But that abyss is very dark until the letting go begins.

PT: Every artist faces the challenge of what to paint and how, but many also concern themselves with how their work engages the “narrative” of contemporary art. You don’t seem distracted by this, rather, you have things and experiences to paint and you concentrate on the many ways you can understand them and know them better by painting them. There’s a richness that comes from the self-granted freedom to pay close, sustained attention to what is personal. Ultimately, do you think that by scrutinizing the immediate, universal issues can be addressed more authentically?

BG: I think you describe how I feel quite well, Brett. I am always aware of what’s happening around me in the art world but from day one my work has been about my own personal journey, though they are never just about me and my story. I don’t set out to address universal issues but I recognize that my issues are not just my own but are shared. All the experiences I paint such as loneliness, rejection, love, death, relationships, the body—and even humor and joy—come straight from my heart and people feel that in my work. There is no wall between me and my paintings. That makes them authentic and I am very proud of that.